Farms around the world are experiencing a surge in avian influenza A(H5N1) infections, commonly called bird flu, among poultry, dairy cows, and even some workers.

Farms around the world are experiencing a surge in avian influenza A(H5N1) infections, commonly called bird flu, among poultry, dairy cows, and even some workers.

Here in Canada, and the USA the spread of bird flu among animal populations is being carefully monitored. While the chance of people becoming infected remains low, bird flu does pose a risk, especially to those who work with wild and domestic birds and animals.

By understanding the basics about bird flu, how the virus spreads, and what preventative measures to take to reduce the risk, you can protect your workers. Here’s what to know and do.

Bird flu basics

Bird flu is a respiratory disease caused by influenza type A virus infections in bird species. Depending on the strain, an infected bird may have no symptoms, mild illness, or serious illness leading to death. The current global increase in bird flu is associated with the highly pathogenic avian influenza strain called A(H5N1).

Bird flu isn’t new. The viral infection has been around for more than a century. In fact, it was first reported as “fowl plague” in 1878 when it caused a wave of chicken deaths in Italy.

Over time, the virus has evolved to infect mammals, many of which hunt, scavenge, or consume infected birds, or are exposed to their contaminated environments.

In both Canada and the USA, there have been sporadic cases of the bird flu A(H5N1) detected in mammals, which include skunks, foxes, racoons, cats and dogs. Most recently, dairy cattle have become infected with the A(H5N1) virus in the U.S.

Because mammals are biologically closer to humans than birds, concern is growing that the virus could mutate to become more contagious to humans.

So far, there is no evidence the virus can spread from person to person. Symptoms and spread

Symptoms and spread

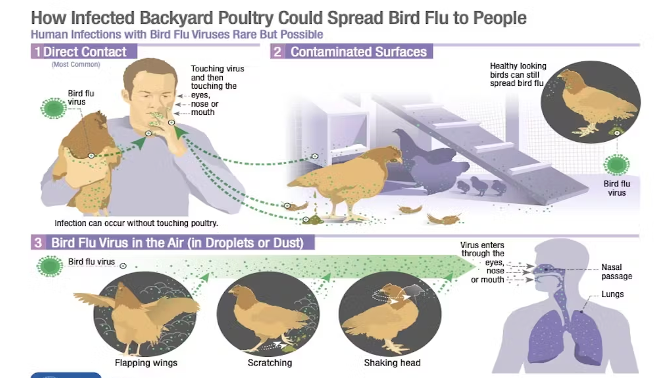

The virus typically spreads among wild aquatic birds and can infect domestic poultry and mammals. Migratory birds can spread the virus to domestic poultry and other species of wild birds and animals along their flight paths.

It can also be spread when infected birds and animals contaminate shared surfaces, equipment, water and feed. When travelling from farm-to-farm, workers can also unknowingly spread the virus on their clothing, boots, or vehicle wheels.

Hunting, slaughtering, butchering, or consuming undercooked or raw meat from wild birds and mammals can also spread the virus.

Signs of infection in birds include sneezing, coughing, swelling around the eyes and head, and lethargy. In domestic chickens, the earliest signs of bird flu are loss of appetite and decreased egg production.

In mammals, symptoms can include fever, pink eye, breathing problems, and neurological signs. In dairy cows, the disease can also lower milk production.

Symptoms of bird flu in people can include coughing, shortness of breath, fever, sore throat, muscle aches, headaches, and tearing, redness and irritation of the eyes. In serious cases, bird flu can cause pneumonia, seizures and death.

It’s important to note that people cannot get infected with the virus by eating thoroughly cooked poultry, eggs and meat. Milk and milk products that have been pasteurized are also safe to consume, which is required to be sold in Canada.

The risk to human

Whenever bird flu viruses are circulating, there is a risk of small clusters of human cases occurring due to exposure to infected animals or contaminated environments and objects.

The virus can spread through infected animal feces and secretions, such as mucus and saliva. Workers exposed to infected birds, dairy cattle or other animals are at higher risk of getting the virus.

Regarding the recent global outbreak, the virus has been found in unpasteurized milk, also known as raw milk, lungs, muscles, and udder tissues of infected dairy cattle.

People may catch the virus by breathing in respiratory droplets or dust containing the virus. People can also be exposed to the virus when infected liquids get into their eyes, including raw milk. Touching contaminated objects and surfaces and then touching the eyes, mouth, or nose, can also lead to infection.

Historically, the number of human infections of bird flu remains low, however, the mortality rate is high. According to the World Health Organization, close to 900 human infections have been reported globally since 2003, of which more than half were fatal.

As of July 3, 2024, the Centre for Disease Control has reported four cases of infected workers in the U.S. associated with the recent A(H5N1) outbreak in dairy cattle. However, there have been no human or dairy cow infections in Canada as of June 19, 2024, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Protecting workers at low risk

Layering on preventive measures to protect workers is key to reducing the risk of the virus, especially for those who care for or handle poultry, wild birds, livestock and other mammals.

Each workplace is unique, and where there is a potential for exposure to bird flu, a risk assessment should be conducted, and appropriate control measures put in place. A risk checklist can help you determine the precautions to take, but all workplaces should follow good biosecurity measures as outlined in the National Biosecurity Standards and other industry standards.

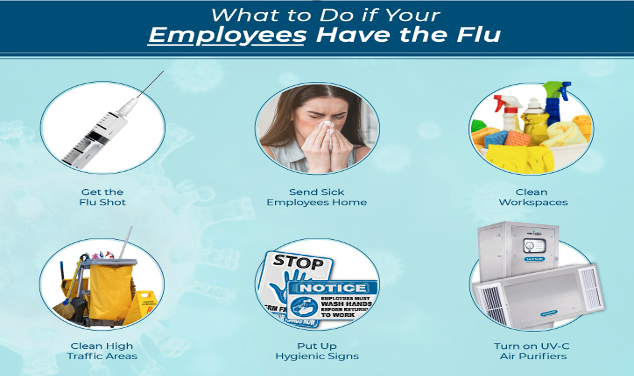

In low-risk settings, including working with healthy animals where there is no known bird flu, ventilate your workplace and encourage employees to work outdoors whenever possible. Increase natural ventilation by opening windows and doors and ensure ventilation equipment is maintained and working properly.

Provide training and signage to promote proper hand hygiene and remind workers to regularly wash their hands with soap and water, and to avoid touching their eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands. If soap and water are unavailable, hand sanitizer containing at least 60 per cent alcohol can be used.

To further reduce risk, advise workers to take breaks, and to eat and drink away from where animals are kept. Workers should wear dedicated clothing and footwear while on the farm, and wash and change their clothes and shower after each shift. Also, if workers are feeling unwell, tell them to stay home.

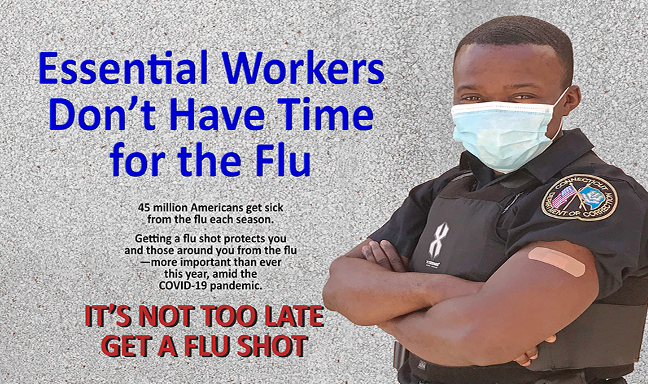

Promoting vaccination for seasonal flu can also help keep workers healthy. Although the flu shot doesn’t protect against bird flu specifically, it can prevent the spread of viruses between people and animals and reduce the risk of becoming infected with both viruses at the same time.

Protecting workers at high risk

In high-risk settings where there is a possible or known bird flu infection, including the culling of infected birds or mammals, follow the low-risk measures listed above and take further precautions.

Workers should avoid direct contact with sick, deceased, or infected animals, as well as environments that are contaminated with their fluids and feces. Infected or sick animals should also be isolated from the rest of the herd and, to prevent cross-contamination, keep vehicles and other equipment away from high-risk areas.

If contact with birds, mammals or heavily contaminated environments is unavoidable, make sure workers are wearing the appropriate personal protective equipment. This includes impervious gloves, rubber boots or boot covers, fluid-resistant coveralls, waterproof aprons, safety glasses and a face shield or safety goggles, and a fit-tested N95 respirator. Proper procedures need to be followed for putting on and taking off personal protective equipment. Make sure reusable personal protective equipment is cleaned and disinfected and disposable personal protective equipment is safely discarded.

High-risk and contaminated areas should be cleaned and disinfected regularly. To clean contaminated areas, wear appropriate personal protective equipment, and use a low-pressure water or mist to spray down the site before cleaning and disinfecting. This will allow dust and debris, like feathers, to settle instead of being airborne, further reducing the risk of workers catching the virus. After cleaning and disinfecting, clothing and footwear should be changed, and hands thoroughly washed.

Responding to an exposure

An emergency response plan should be in place for workplaces where there is a potential for workers to be exposed to bird flu. A documented plan should outline how to prevent, detect, and respond to worker infections.

When a worker is exposed to a suspected or known source of the bird flu and becomes ill, even with mild symptoms, it should be reported to the local public health authority, worker’s compensation board, and the health and safety regulator.

Workers should also seek medical attention from their healthcare provider if they are feeling unwell or experiencing symptoms. Call 911 immediately if a worker experiences life-threatening symptoms. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) also needs to be notified if any animal under the employer’s care is suspected of having the bird flu.

The exposed worker should also stay home, away from others, and follow proper hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette. Clean and disinfect areas, tools, equipment, and other items that may be contaminated. An investigation should also be done to determine the cause of exposure and appropriate measures to help prevent another occurrence.

Bio:

Dr. Bill Pomfret of Safety Projects International Inc who has a training platform, said, “It’s important to clarify that deskless workers aren’t after any old training. Summoning teams to a white-walled room to digest endless slides no longer cuts it. Mobile learning is quickly becoming the most accessible way to get training out to those in the field or working remotely. For training to be a successful retention and recruitment tool, it needs to be an experience learner will enjoy and be in sync with today’s digital habits.”