Last month’s Insight explained that MSS 1000 is a universal management system standard that facilitates the creation of fully integrated management systems without boundaries addressing the totality of the management of an organisation irrespective of size and type. We now look at how it promotes a holistic management of uncertainty.

Last month’s Insight explained that MSS 1000 is a universal management system standard that facilitates the creation of fully integrated management systems without boundaries addressing the totality of the management of an organisation irrespective of size and type. We now look at how it promotes a holistic management of uncertainty.

Table 1.

Organisations behave like conscious superorganisms comprising structures and processes that collectively deliver their purpose, equitably satisfy stakeholders and make the best use of resources. Optimising performance requires that management attention is focused on the organisation’s ‘normal product/service delivery’, ‘contingency’ and ‘change’ structures and processes. An integrated management approach is essential because it is these same physical and virtual structures and processes that give rise to the multiple dimensions of performance that impact product/service quality, health, safety, environment, financial, information, security and reputation.

Organisations behave like conscious superorganisms comprising structures and processes that collectively deliver their purpose, equitably satisfy stakeholders and make the best use of resources. Optimising performance requires that management attention is focused on the organisation’s ‘normal product/service delivery’, ‘contingency’ and ‘change’ structures and processes. An integrated management approach is essential because it is these same physical and virtual structures and processes that give rise to the multiple dimensions of performance that impact product/service quality, health, safety, environment, financial, information, security and reputation.

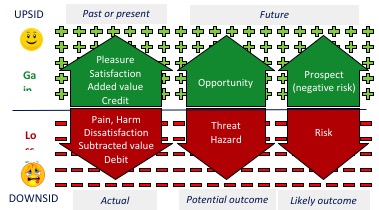

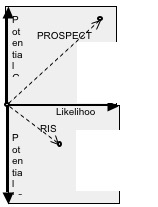

The standard takes a holistic approach to managing the potential myriad of uncertainties that may confront an organisation and requires that the organisation’s foundation planning first identifies the significant stakeholders, their needs, expectations, aspirations and their power to influence the organisation. Overall success depends on seeking to equitably maximise gain while minimising loss as judged relativistically by each of the stakeholders. Likely potential gain is expressed as prospect while likely potential loss is expressed as risk. ‘Prospect and risk’ are a natural upside and downside pair containing an uncertainty element and contrasts with other typical upside and downside pairs such as ‘credit and debit’ and ‘opportunity and threat’ etc. shown in Figure 1.

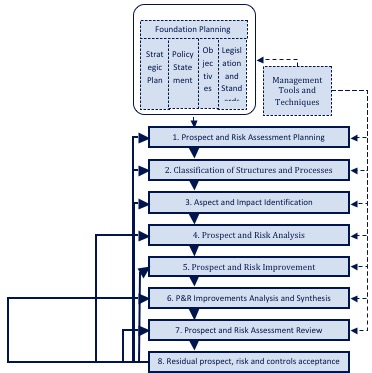

The three principal classes of upside and downside terminology used in MSS 1000 are; ‘already realised outcomes’, ‘outcomes that may potentially occur’ and ‘likely gains or losses’. The identification of potential outcomes precedes the assessment of likely outcome based on or informed by actual past or present outcomes data within our knowledge. The full cycle of prospect and risk assessment is shown in Figure 2 and is elaborated in considerable detail within the standard including examples of qualitative unified prospect and risk rating scales and how assessment can be used to drive proportionate planned monitoring.

Table 2.

Throughout MSS 1000 it seeks to add value to an organisation by improving its physical and virtual structures and processes so that prospect is increased and risk is reduced. Two principal complementary approaches are employed. One is the adoption of generic prospect and/or risk improvement practices e.g. not assigning personnel to posts, roles, of tasks unless they are competent or appropriately supervised. The other is to conduct appropriate prospect and risk assessments as per Figure 2 in order to develop proportionate prospect and/or risk improving controls. These two approaches operate within a ‘plan do check act’ management cycle explained in last month’s article. It should be noted that safety and security are the only two that are concerned with preventing loss by managing risk – all of the others such as commerce, goods/services quality, reputation, health and environment need to address the management of prospect and risk in a holistic and balanced way.

Throughout MSS 1000 it seeks to add value to an organisation by improving its physical and virtual structures and processes so that prospect is increased and risk is reduced. Two principal complementary approaches are employed. One is the adoption of generic prospect and/or risk improvement practices e.g. not assigning personnel to posts, roles, of tasks unless they are competent or appropriately supervised. The other is to conduct appropriate prospect and risk assessments as per Figure 2 in order to develop proportionate prospect and/or risk improving controls. These two approaches operate within a ‘plan do check act’ management cycle explained in last month’s article. It should be noted that safety and security are the only two that are concerned with preventing loss by managing risk – all of the others such as commerce, goods/services quality, reputation, health and environment need to address the management of prospect and risk in a holistic and balanced way.

Prospect is sometimes referred to as negative risk but it is far too important not have an unequivocal name. It is the pursuit of gain through the intelligent and creative maximising of prospects which is the principal driver that delivers an organisation’s purpose. Typical prospects of improving stakeholder satisfaction include securing a given sized contract, employing personnel of a desired capability, growing the company to a particular size, capturing a given portion of the market, achieving a given level of customer satisfaction etc. Prospect is not just the mirror of risk but takes the lead in decision making processes. Planning involves first identifying and assessing the potential prospects capable of delivering the purpose of the organisation, adding value and equitably satisfying the needs, expectations and aspirations of stakeholders while making the best use of resources.

Table 3.

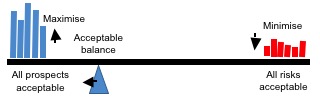

However, risks of various types will inevitably be associated with each potential prospect adding to the complexity of decision making and the need to equitably balance the multiple prospect/risk requirements of stakeholders – refer to Figure 3. Taken on its own, risk is always bad and to be avoided but inevitably risks have to be taken in order to reap the benefits from exposure to prospect – prospects and risks inextricably co-exist. Plotting prospects and the associated risks on a prospect/risk diagram can help create a good conceptual model and get things in perspective prior to making a decision – refer to Figure 4. The realisation of prospects and risks may occur instantly or gradually over time e.g. an explosion or a slow deterioration in health, the loss of a key customer or the slow decline of sales

However, risks of various types will inevitably be associated with each potential prospect adding to the complexity of decision making and the need to equitably balance the multiple prospect/risk requirements of stakeholders – refer to Figure 3. Taken on its own, risk is always bad and to be avoided but inevitably risks have to be taken in order to reap the benefits from exposure to prospect – prospects and risks inextricably co-exist. Plotting prospects and the associated risks on a prospect/risk diagram can help create a good conceptual model and get things in perspective prior to making a decision – refer to Figure 4. The realisation of prospects and risks may occur instantly or gradually over time e.g. an explosion or a slow deterioration in health, the loss of a key customer or the slow decline of sales

An acceptable balance of prospect(s) and risk(s) for a particular organisation depends on what they are and the degree that they impact stakeholder needs, expectations and aspirations. Differing stakeholder views, their prospect and risk tolerabilities and their power to exercise influence makes decision making even more challenging and necessitate the exercise of pragmatism and good judgement. The standard requires that organisations define their own arrangements for ensuring that stakeholder requirements are determined and that prospect and management controls are established. These should be based on or informed by appropriate qualitative or quantitative prospect and risk assessments conducted only to a degree that adds value or to comply with a stakeholder requirement e.g. regulatory compliance. Prospect and risk management can never be perfect and it can only be justified when it adds value.

An acceptable balance of prospect(s) and risk(s) for a particular organisation depends on what they are and the degree that they impact stakeholder needs, expectations and aspirations. Differing stakeholder views, their prospect and risk tolerabilities and their power to exercise influence makes decision making even more challenging and necessitate the exercise of pragmatism and good judgement. The standard requires that organisations define their own arrangements for ensuring that stakeholder requirements are determined and that prospect and management controls are established. These should be based on or informed by appropriate qualitative or quantitative prospect and risk assessments conducted only to a degree that adds value or to comply with a stakeholder requirement e.g. regulatory compliance. Prospect and risk management can never be perfect and it can only be justified when it adds value.

The standard can be freely downloaded via http://bit.ly/1J9te4Q

Biography – IAN DALLING

Ian Dalling DipEE, BA (Hons), CEng, MIMechE, MIET, MIOSH, FCIQ, CQP, RSC Chartered Electrical and Mechanical Engineer and Integrated Management Practitioner

Ian’s 50 years of experience has spanned design, construction, commissioning, operation, and decommissioning of nuclear power plants and other industry sectors. While at CEGB/Nuclear Electric, he was a senior authorised person for nuclear, mechanical and electrical systems up to 400 kV and held posts in operations, commissioning, management services, planning and quality assurance.

From 1990, he was a quality and risk management consultant with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. He managed the peer review of the decommissioning safety case for the UK Steam Generating Reactor, was the quality manager for a European Notified Body administering product safety regulations, and worked on a variety of safety cases and management systems for major organisations. He served on the European Process Safety committee and the British Standards Committee that developed the occupational safety and health standard (BS 8800:1996). He was a member of an international team that reviewed the safety management arrangements of the Lithuanian Ignalina RBMK nuclear power plant following the Chernobyl accident.

He has operated his own quality and risk management consultancy since 1999 with clients in the nuclear, construction, rail, oil and gas, medical devices, medical services and laboratory services sectors in the UK and overseas. He chairs the CQI Integrated Management Special Interest Group, which produced the universal management system standard MSS 1000:2014.