In this article, we intend to offer a realistic perspective on corporate social responsibility. First we offer our perspective on the related concepts of corporate social responsibility and sustainability, clarifying why anyone in the business community should spend some energy on them. Then we relate corporate social responsibility to corporate risk.

Focusing corporate risk on the risk in future developments, we then see the background for the challenges within corporate social responsibility. From the complexities around those challenges, we then go to developing business, which then brings us to our conclusion. The conclusion has to make sense in managerial terms and that is why we give the reader a twelve step program to effectuate improvements in terms of corporate social responsibility.

Focusing corporate risk on the risk in future developments, we then see the background for the challenges within corporate social responsibility. From the complexities around those challenges, we then go to developing business, which then brings us to our conclusion. The conclusion has to make sense in managerial terms and that is why we give the reader a twelve step program to effectuate improvements in terms of corporate social responsibility.

Introduction: What is CSR and Why Invest the Time and Energy?

On the surface, things appear normal. The status quo of the balance between the public sector and the private sector in regards to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Governance, Risk and Compliance (GRC) isn’t to everyone’s liking, but it is still a work in progress after a fashion. We are muddling through. Or are we? Is the pot about to boil as trends converge in these areas? And how can the business world respond to it?

Defining CSR: Difficult but not Impossible

Various definitions and models of CSR go around (for an overview, see: David Vogel, The Market for Virtue). What they have in common is a preference for a wider range of roles of the organization and its members, along with new responsibilities and opportunities.

This ties in with the stakeholder approach to business. This approach was coined by Ed Freeman in his “Strategic Management – A stakeholder Approach” (1984) as aimed at “any person or group that can affect or is affected by the achievement of a corporation’s purpose”. This approach is not meant to displace the shareholder model of ownership of companies, either publicly traded or privately held. It mainly helps to make clear how an organization depends on the behavior of certain entities in its own environment in order to achieve its goals and be successful. This model was taken up in the thinking about Corporate Social Responsibility for obvious reasons: when speaking of responsibilities, you need to have an idea towards whom there would be responsibilities. Those responsibilities are partly chosen, as when a company chooses to cater to certain customers and the business relationships with those customers bring responsibilities with them; often they are not voluntarily chosen by an organization, but result from its activities, such as when regulatory agencies and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) announce themselves, with varying degrees of legitimacy, as stakeholders to the organization’s activities. The variety of potential stakeholders indicates the social dimension in Corporate Social Responsibility.

We can see the influence of this approach in the definition of CSR offered by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development:

CSR is the commitment by organisations to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as the local community and society at large.

We can see from this definition that CSR is often taken to mean a bit more than just honouring basic obligations.

These days, the concepts of Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability go hand in hand, especially in the business world, where we see some companies using one definition while others prefer another definition, while addressing more or less the same issues. Although CSR is not necessarily about the future, as sustainability is, by taking various stakeholders into account we see interests brought in that have a long term scope. This would also mean going beyond honoring basic obligations. But, as we shall see, that does not necessarily mean going beyond an organization’s strategic goals and objectives.

The above definitions tie in with the most important definition of Sustainability, given in the 1987 UN report “Our Common Future”, known henceforth as the Brundland definition:

“Providing for your needs of today in such a way that you do not limit the options for future generations to provide for their own needs”.

This definition may sound a bit negative, as it hardly veils the accusation that before businesses (and other organizations) have been achieving their goals in ways that would inevitably lead to problems further in the future. Although there is ample truth to that accusation, it may be more inspiring to find a different way to express the same message. Also, the Brundland definition has been criticized for not being precise and operational enough. We can also find the definition “sustainability is the ability to continue a defined behavior”. To put this in business terms, it means the ability to continue the business indefinitely. But this has to be understood in terms of stakeholder management, which makes us think of what is meant by the term “business”. Understanding what is meant by the term “business”, sustainability would mean “the ability for the network of stakeholders, including the entity itself, to perpetuate itself”. In fact, this may be far more natural than ignoring sustainability. After all, it is apparently part of human nature since the dawn of time to create what lasts longer than our own lifespan; one of the driving forces behind great art. Why would business run counter to that?

We can also say that where sustainability is not always clear, avoiding the unsustainable is much clearer. Some of the unsustainable has been addressed by laws, such as environmental, health, safety and by society, such as the use of child labor. But here we see the difference between law and ethics: certain activities are sometimes not strictly forbidden by law, but frowned upon by some stakeholders. We call this “lawful, but awful”.

Corporate Social Responsibility may need attention, and offer opportunities, throughout the spectrum of business-activities. We can see CSR as strategic, operational and tactical. This results in the challenge to bring the responsibilities to these levels, and the actions associated with those responsibilities, in line with each other.

Responsibilities are part of business and come into play whenever business decisions are made. This is a fact of life. With growing awareness of the issues brought in by sustainability and CSR, a new range of responsibilities have come into view, ranging from looking further into sourcing (chain responsibility) to being responsible for the lifestyles of clients, not to mention future generations.

Establishing Goals and Objectives for the CSR Program

Developing a dynamic CSR program entails rethinking short term approaches to embedding long term “ways of doing business”; that is changing the culture of the organization. While many organizational processes put the focus on the short term, usually very understandably, we also have many years of experience with how things can go very wrong if the short term creates limitations and unsustainability. We can therefore say that knowing how to manage short term thinking is a way of managing risk, while at the same time we see in addition that looking beyond the short terms offers opportunities we would not otherwise have seen.

Can CSR Contribute to Your Organization’s Risk Management Activities?

“The more you know, the more you know you don’t know.” – Socrates

Awareness of risk can lead to unforeseen risk behaviors based on knowledge that is sufficiently convincing to lead to false positives. Knowledge is an opening door to understanding risk; the risk of knowledge is knowing how much you do not know (ignorance is bliss). Unfortunately we have a very limited understanding of where risk is or where risk is going to materialize. Here is a small excerpt from “I, Pencil” by Leonard E. Read. The reason for this example is that we all use or have used pencils in our lifetimes. The pencil is a simple implement, right?

“I am a lead pencil – the ordinary wooden pencil familiar to all boys and girls and adults who can read and write. Writing is both my vocation and avocation; that’s all I do. Simple? Yet, not a single person on the face of the earth knows how to make me.

That sounds fantastic, doesn’t it? Especially when we realize that there are about 14 billion pencils produced in the U.S.A. alone, each year.

Consider the complexity of the pencil and then think about the complexity of risk. A pencil looks rather simple and yet when you analyze it the components become a maze of complexity. Risk is much the same. Risk may appear simple and straightforward. Yet, when you analyze risk, you begin to realize the complexity of what you are looking at. Few really comprehend this complexity and, as such, risk is often simplified and discounted.

How resilient and nimble is your risk management and/or business continuity program? Are these programs based solely on compliance with regulations? Do you really understand the identified risks that you found when you did your risk assessment and/or business impact analysis? Or have you created “False Positives” and a vulnerabilities that are transparent?

A question should be stirring in your brain – what risks, business impacts, etc. have we mislabeled because we did not analyze them in sufficient depth? Do we assess the volatility of risk? And, how about velocity of risk? More importantly do our programs provide us with early warning of risk realization?

We must realize that the limitations of our knowledge will be exposed when we implement our CSR program initiatives. This is partially due to the fact that we cannot predict how people will react to CSR program initiatives. It is also due to the fact that we tend to do less in depth analysis as a result of the focus of our activities on CSR and less on resilience, risk management and business continuity.

Risk is in the Future not the Past

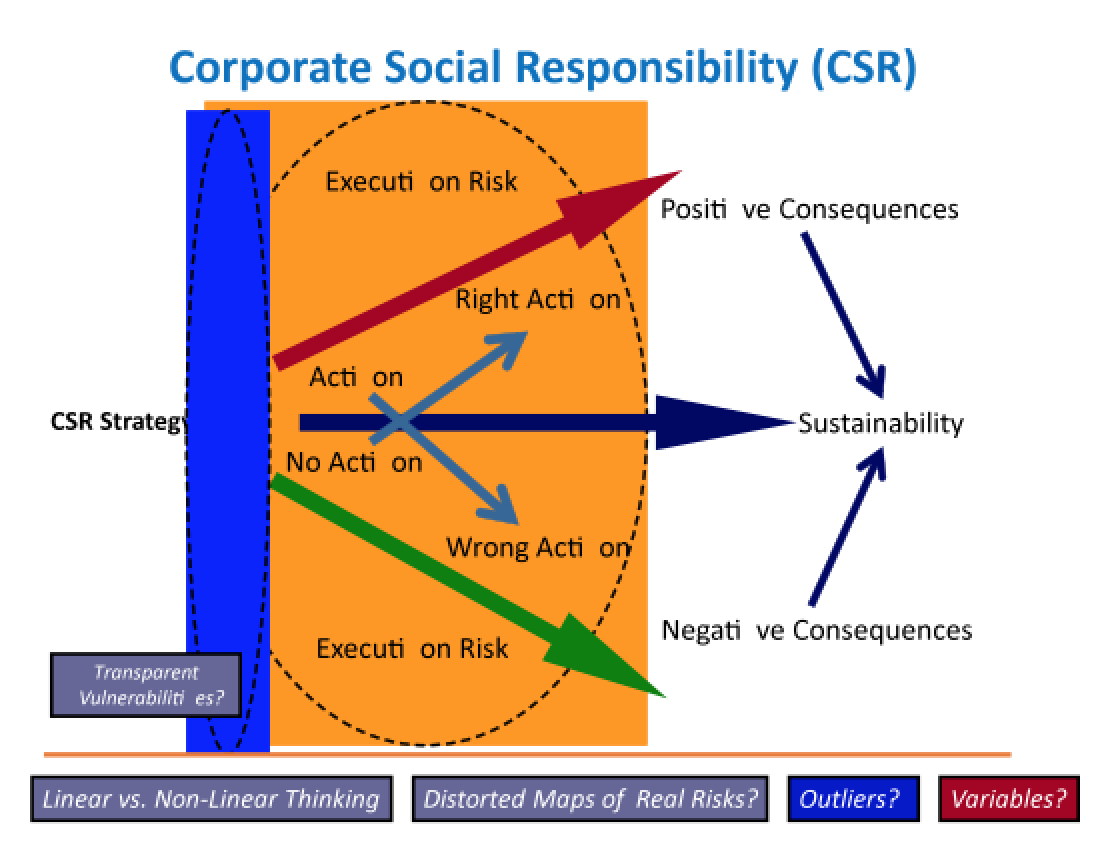

During the cold war between the United States of America and the former Soviet Union, there were thousands of nuclear warheads targeted at the antagonists and their allies. The result, the concept of mutually assured destruction was created. The term was used to convey the idea that neither side could win an all-out war; both sides would destroy each other. The risks were high; there was a constant effort to ensure that “Noise” was not mistaken for “Signal” triggering an escalation of fear that could lead to a reactive response and devastation. Those tense times have largely subsided, however, we now find ourselves in the midst of global competition and the need to ensure effective resilience in the face of uncertainty. As depicted in the figure below, Executing the CSR strategy one may encounter transparent vulnerabilities that are only readily seen in hindsight. When implementing a CSR program there are execution risks that must be addressed: is the action the right action or the wrong action? Can taking no action be the right thing to do, or the wrong thing to do? What are the outliers and variables that we need to track and take into consideration? Are we dealing with distorted maps of reality? How can we overcome biases and linear thinking?

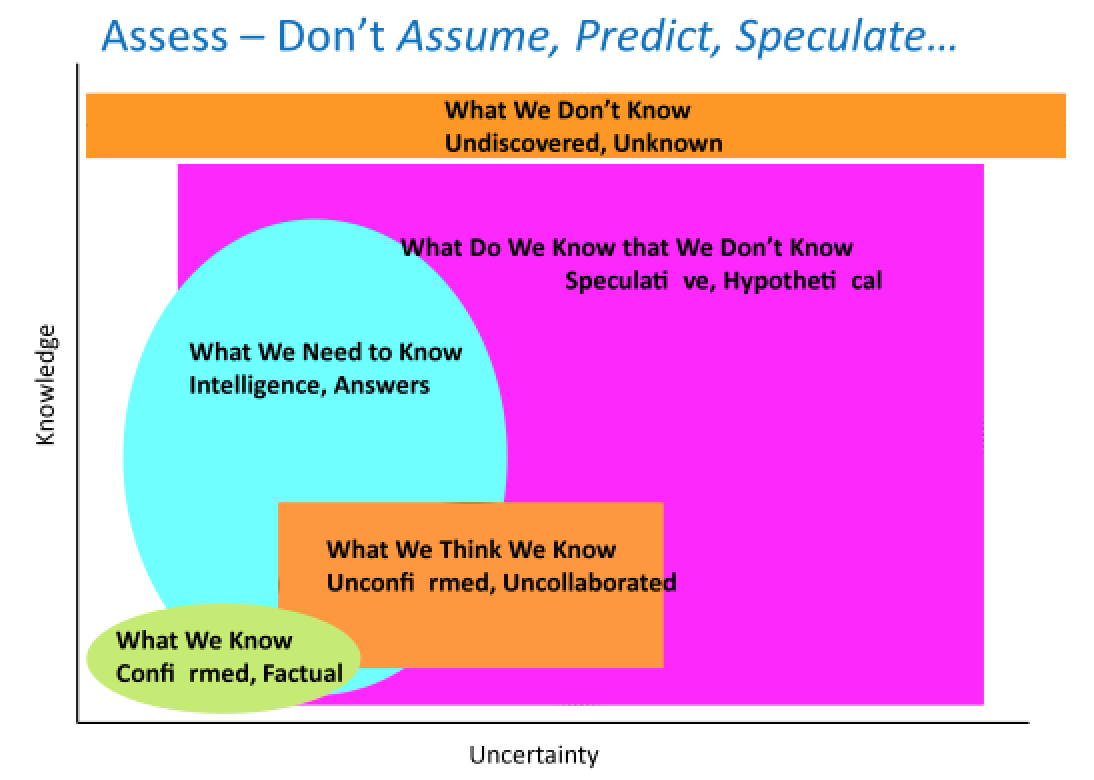

Jeffrey Cooper offers some perspective: “The problem of the Wrong Puzzle. You rarely find what you are not looking for, and you usually do find what you are looking for.” In many cases the result is irrelevant information. As the figure below depicts, we need to assess, not assume or, attempt to predict, or speculate on. The spheres below give a perspective on what we know, tend to think we know, tend to speculate upon. We have to acknowledge that what is unknown (the Unknown Unknowns) will remain so, until discovered and labeled.

Jeffrey Cooper offers some perspective: “The problem of the Wrong Puzzle. You rarely find what you are not looking for, and you usually do find what you are looking for.” In many cases the result is irrelevant information. As the figure below depicts, we need to assess, not assume or, attempt to predict, or speculate on. The spheres below give a perspective on what we know, tend to think we know, tend to speculate upon. We have to acknowledge that what is unknown (the Unknown Unknowns) will remain so, until discovered and labeled.

Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber would define this as a Systemic Operational Design (SOD) problem – a “wicked problem” that is a social problem that is difficult and confusing versus a “tame problem” not trivial, but sufficiently understood that it lends itself to established methods and solutions. I think that we have a “wicked problem”.

Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber would define this as a Systemic Operational Design (SOD) problem – a “wicked problem” that is a social problem that is difficult and confusing versus a “tame problem” not trivial, but sufficiently understood that it lends itself to established methods and solutions. I think that we have a “wicked problem”.

As Milo Jones and Philippe Silberzahn in “Constructing Cassandra: Reframing Intelligence Failure at the CIA, 1947–2001” write, “Gresham’s Law of Advice comes to mind: “Bad advice drives out good advice precisely because it offers certainty where reality holds none”” (page 249). False certainty may be worse than uncertainty.

Just because it is the right thing to do, doesn’t make it the easy thing to do. But doing only the easy things is not a wise strategy. At least, the successful organizations we all know did not get to be there by only doing easy things; rather, in those companies success was achieved by having the guts to do what in other organizations they were hesitant about.

Now Let Us Apply these Insights to Corporate Social Responsibility

Professionals responsible for CSR, GRC and related areas need to rethink some of the paradigms of the current perspectives and practices associated with CSR, GRC, etc. All too often we tend to fall back on what are considered the tried and true ways of doing things. This essentially leaves us in two camps; the first, evolved out of information technology and disaster recovery and the second, evolved out of emergency preparedness (tactical planning), financial risk management (operational) and strategic planning (strategic). These two camps each offer much to be desired. The first, having renamed disaster recovery and calling it business continuity (BCP) still retains a strong focus on systems continuity rather than true business continuity; but this is not a bad thing. The second, has begun a forced merger of sorts; combining the varied practices at three levels (tactical, operational and strategic) and renaming it, enterprise risk management (ERM). The second group still retains strong perspectives on risk management; that is why I have divided it into the three sub-groups (tactical, operational and strategic).

Complexity, in Effect, is Changing the CSR Paradigm

Complexity cannot be approached with a dependence on only mathematics. Complexity also cannot be dealt with just through intuition. There is a balance that has to be developed between the two in order to get a perspective on risk, threat, hazard, consequence and business impact. As you assess you have to start mapping the complexity that evolves out of the identification of a risk, threat, hazard, etc. You need to think in three dimensions – strategic, operational and tactical. Each feeds into the others and gives you a list of issues that you can relate to the identified risk, threat, hazard, etc.

Taken as a continuous and never ending process, you begin to realize that risk, threat, hazard, etc. can only be buffered and that the buffering process has to be refreshed in order to maintain risk parity. This requires constant analysis and asset allocation to maintain parity.

Making CSR a Way of Doing Business Versus an Adjunct to Business Operations

First and foremost you need to understand the commitments that your organization is making. The need to establish and maintain an ongoing dynamic CSR program is essential, on the condition that it is in line with strategic purpose and core processes. In order to facilitate administration and planning requirements, a record of all initiatives should be retained. Senior Management and staff must be kept well informed, just as they have to be informed about the other aspects of the company’s core processes. Information is an institutional asset and essential to holding decision makers to their responsibilities. It must be shared and managed effectively. Information management is also critical during a disruptive event. The need for active systems to provide information on materials, personnel, capabilities information on materials, personnel, capabilities, and processes is essential. It is extremely important to have a system (and adequate back-up systems) in place that serves to identify, catalog, set priorities and track issues and commitments relating to CSR activities. You are responsible for what you know and for what you are expected to know.

Without checks and balances in place programs can run afoul and lead to disastrous consequences; as the recent Volkswagen “dieselgate” software programs and the Theranos fraud regarding blood testing results.

Conclusions: The Bottom Line for the Business Community

It’s all about targeted flexibility, the art of being forward thinking and resilient, rather than reactive to short term trends and events. We argue that the core of sustainability (and CSR comes down to the same) that is about the resilience of you as an individual, as an organization and as a social context.

Michael J. Kami, author of the book, ‘Trigger Points: how to make decisions three times faster,’ wrote that an increased rate of knowledge creates increased unpredictability. Stanley Davis and Christopher Meyer, authors of the book ‘Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy,’ cite ‘speed – connectivity – intangibles’ as key driving forces. Kami outlines 12 steps in his book that provide some useful insight for CSR development and sustainability:

Step 1: Where Are We? Develop an External Environment Profile

Key focal point: What are the key factors in our external environment and how much can we control them? How can we be a good corporate citizen and adhere to society’s expectations of social responsibility?

Step 2: Where Are We? Develop an Internal Environment Profile

Key focal point: Build detailed snapshots of your business activities as they are at present. Look to see what areas are best suited to CSR program development and then look to the harder areas and develop a culture of change and responsibility.

Step 3: Where Are We Going? Develop Assumptions about the Future External Environment

Key focal point: Catalog future influences systematically; know your key challenges and threats. Focus on applying CSR as a way of doing business instead of an adjunct to the business operations; continuous analysis (“Active Analysis”) and involvement of the “Value Chain”, government, society in general to shape and explain CSR initiatives.

Step 4: Where Can We Go? Develop a Capabilities Profile

Key focal point: What are our strengths and needs? How are we doing in our key results and activities areas? Develop an integrated evaluation program for CSR, GRC and continuity of the business.

Step 5: Where Might We Go? Develop Future Internal Environment Assumptions

Key focal point: Build assumptions, potentials, etc. Do not build predictions or forecasts! Assess what the future business situation might look like. Ensure that the CSR and GRC programs are flexible enough to change with alteration of strategy, goals and objectives.

Step 6: Where Do We Want to Go? Develop Objectives

Key focal point: Create a pyramid of objectives; redefine your business; set functional objectives. Integrate CSR and GRC thinking into the culture of the organization, mission, vision and values.

Step 7: What Do We Have to Do? Develop a Gap Analysis Profile

Key focal point: What will be the effect of new external forces? What assumptions can we make about future changes to our environment? Ensure that the CSR and GRC programs are based on forward looking research and are flexible to change.

Step 8: What Could We Do? Opportunities and Problems

Key focal point: Act to fill the gaps. Conduct an opportunity-problem feasibility analysis; risk analysis assessment; resource-requirements assessment. Build CSR/GRC action program proposals.

Step 9: What Should We Do? Select Strategy and Program Objectives

Key focal point: Classify CSR strategy and program objectives; make explicit commitments; adjust objectives.

Step 10: How Can We Do It? Implementation

Key focal point: Evaluate the impact of CSR and GRC programs.

Step 11: How Are We Doing? Control

Key focal point: Monitor the external environment and engage. Analyze fiscal and physical variances. Conduct an overall assessment of CSR and GRC effectiveness.

Step 12: Change What’s not Working Revise, Control, Remain Flexible

Key focal point: Revise CSR and GRC strategy and program objectives as needed; revise explicit commitments as needed; adjust objectives as needed.

We live in a world full of consequences; consequences to ourselves and to the people and other entities around us. Our decisions need to be made with the most information available with the recognition that all decisions carry with them flaws due to our inability to know everything. This is especially the case when we pretend to know everything by ourselves, without recognizing the ideas and perspectives of our stakeholders. Our focus should be on how our flawed decisions establish a context for flawed CSR and GRC programs, leading to misunderstanding and conflict with society’s perception of our actions. If we change our thought processes from chasing symptoms and ignoring consequences to recognizing the limitations of decision making under uncertainty we may find that the decisions we are making have more upside than downside and that our CSR and GRC programs facilitate the attainment of our strategy, goals and objectives; both in the short and long term.

About the Authors

Geary Sikich – Management Advisor, Author and Speaker

Contact Information: E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com. Telephone: 1- 219-922-7718.

Geary Sikich is a seasoned risk management professional who advises private and public sector executives to develop risk buffering strategies to protect their asset base. With a M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance, Geary’s focus is human capital: what people think, who they are, what they need and how they communicate. With over 25 years in management consulting as a trusted advisor, crisis manager, senior executive and educator, Geary brings unprecedented value to clients worldwide.

Geary is well-versed in contingency planning, risk management, human resource development, “war gaming,” as well as competitive intelligence, issues analysis, global strategy and identification of transparent vulnerabilities. Geary began his career as an officer in the U.S. Army after completing his BS in Criminology. As a thought leader, Geary leverages his skills in client attraction and the tools of LinkedIn, social media and publishing to help executives in decision analysis, strategy development and risk buffering. A well-known author, his books and articles are readily available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and the Internet. He developed a webinar on problem solving and critical thinking: https://www.execsense.com/ceo/problem-solving-and-critical-thinking-skills/

Joop Remmé Ph.D. – lecturer, researcher, consultant

Contact information: remme@corporate-responsibility-future.eu / www-corporate-responsibility-future.eu

Joop Remmé has a long track-record as a lecturer within MBA schools and as a consultant.

Joop Remmé has over the past 30 years been teaching and consulting on management development, CSR/ sustainability, stakeholder management and corruption/integrity. He has also published on these subjects in academic journals and is a regular speaker at conferences. He recently authored a webinar on Managing the Sustainability Agenda: https://www.execsense.com/c-suite/sustainability-agenda-how-to-manage