Heightened Awareness or Reactive, Backwards Looking?

Heightened Awareness or Reactive, Backwards Looking?

From financial crises to energy catastrophes to earthquakes and threats of terrorism, we hear a lot about events that challenge our ability to identify and manage risk. Unfortunately some of the things that emerge from many of these events are reactive regulatory rules and requirements.

What this means is that businesses and governments need to be even more vigilant in their prosecution of enterprise risk management initiatives. Private and Public Sector operations are complex and becoming more complex as more entrants to the global marketplace compete for fewer and fewer available resources at an ever quickening pace.

So, is society, as we know it, on the verge of collapse, destruction, another stone-age? Seems that you cannot turn on a television, radio or the plethora of personal communication devices available without headlines screaming at you about people with Molotov cocktails, car bombs, murders, floods, fires, car crashes, riots and, celebrities gone wrong. Sovereign nations are going bankrupt, sabers are being rattled; how you might ask, is it all going to end?

Unpredictability is the new normal

After an event we have a tendency to exaggerate the magnitude of the risks we become aware of. For example, in the post-September 11th timeframe there was a push by many organizations for more security, more anti-terrorism planning, target hardening and a general perception that everything was a target. This phenomenon lasted a very short time; as the reality grew that increased security, target hardening, etc. came with a cost. Another example would be the threat of a pandemic. When the Bird Flu (H5N1) was being touted as the next pandemic and Oprah had excited experts on her show speaking to an alarmed audience of mainly women, we saw a surge in desperate preparations to deal with an, as yet, undeclared pandemic. Masks and other medical options (Tamiflu, etc.) were in short supply and highly sought after. Yet, few considered a key factor: that the potential pandemic would last more than the short term planning that was being developed. Hence, when faced with the economics of getting masks for employees, etc. few organizations asked the question, how many and for how long? I calculated for one client with 14,000 employees that providing 1 mask per day for each employee over the course of a 500 – 800 day pandemic (research the literature – this is the normal timeframe for a pandemic to run its course) this would amount to approximately 12,000,000 masks (at the time almost impossible to purchase due to manufacturing shortfalls). The cost estimate and the associated storage and distribution system required for getting the masks to each employee daily further shocked the decision makers. Then they asked, realizing that the cost was prohibitive to business survival) what the alternative was? We instituted a program of education, protocols addressing everything from coughing to janitorial services and an assessment of the economic issues (i.e. would there be a greater demand for the organization’s services/products and would the workforce be available to meet the demand and visa-versa). When an actual declaration for H1N1 was made by the World Health Organization, the organization discounted the event and their planning protocols and had to be convinced that they needed to provide guidance to employees (updating the situation, etc.) as they had not experienced any H1N1 cases within their employees.

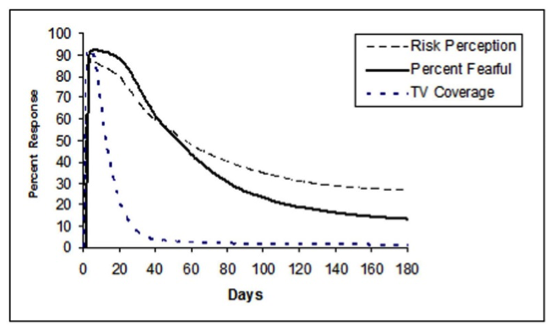

There is a tendency to be reactive to media driven events, such as pandemics, terrorism, severe weather, etc. This reactive response is generally short lived; when the event loses its media appeal and the next big story emerges we tend to forget and fall into complacency.

The fact is, we cannot plan for all contingencies. It would tantamount to making a statement like this: “We’ve considered every potential risk, except the risk of avoiding all risks”. The challenge for planners is to overcome the tendency to rationalize in the post-event environment. Rarely do we see an assessment of what worked and what did not work in the post-event timeframe. This is due, partly, for the desire to return to “business as normal”.

Unpredictable Frustration

The biggest single threat to business/government is staying with a previously successful operating model too long and not being able to adapt to the fluidity of situation. I think that as humans generally we would like the future to be more deterministic and many do not like the thought of an uncertain, ambiguous and dappled future, even more disliked is the thought that we may make that future worse by our actions. Somehow software, like numbers, entices us with a promise of certainty and clarity where no really exists and if things go bad it gives us something to blame which is unable to argue with us as to where the fault really lies.

Are we the victims of flawed mental models that influence our perceptions after an event? Daniel Kahneman in his book, “Thinking Fast and Slow” points out that we tend to fall back on our biases when analyzing and making decisions. Kahneman point out a myriad of biases that affect our perception and decision making. It is important to acknowledge that bias will affect our perceptions of risk after an event. Figure 1, entitled: “Risk Perception – Influence of Media Coverage” depicts the decline in risk perception and fear as media coverage declines.

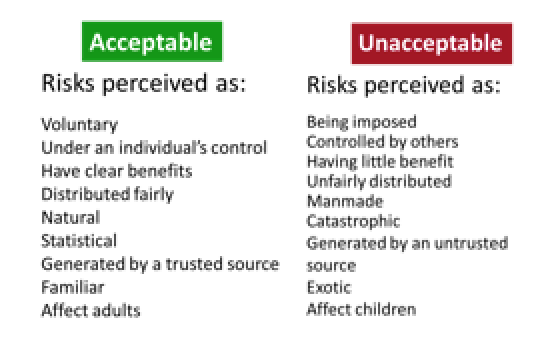

Peter Sandman, of Princeton University provides some examples of what is considered acceptable and unacceptable when it comes to communicating risk to populations:

Peter Sandman, of Princeton University provides some examples of what is considered acceptable and unacceptable when it comes to communicating risk to populations:

As Sandman points out: Public perception of risk may not bear much resemblance to Risk Assessment. However, when it comes to their accepting risk one thing is certain: “Perception is Reality”. People perceive risks differently; people do not believe that all risks are of the same type, size or importance. Hence, communicating risk (before and after events) is critical to planners and decision makers in order to establish credibility and to get buy-in for participation in pre- and post-event planning.

Living in a Non-Predictive World

We know very little about how different highly disruptive, nonlinear changes might interact with and amplify one another. We tend to think in a linear manner when it comes to pre- and post-incident response. We do not factor in nonlinearity in regard to risk perception. The simple fact is: evolution creates change, collateral factors come into play; uniqueness is created in the way that evolution occurs. Nonlinear evolution of events in combination with reactions to events changes our perception after-the-fact. We are reactive for the most part. And when you are reactive you tend to be affected by reaction to change. We do not see the consequences clearly and the long lasting effects are not readily apparent. For example, many have labeled the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico a “Black Swan” event. Nassim Taleb, defines a “Black Swan” as having three characteristics: it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.

Taleb continues by recognizing what he terms the problem – “Lack of knowledge when it comes to rare events with serious consequences.” It is interesting to find that, with a little research, that events such as the Deepwater Horizon are not that rare in offshore drilling. Since 1956 there have been over 200 incidents – from sunk rigs to blowouts, collapse and hurricanes, storms, etc.

Altered States and Risk Management

Events are not shared by people in the same manner. Each of us perceives the event differently due to bias and consequences. We know very little about how different highly disruptive, nonlinear changes might interact with and amplify one another. Therefore, we need to approach risk assessment as an ongoing process, recognizing that risk does not go away with our mitigation efforts. Rather, risk transforms and we need to constantly buffer risk in order to minimize its effects if realized. We need to achieve “risk parity”. Risk parity is an approach that focuses on the allocation of assets to risk, usually defined by exposure, velocity and volatility rather than allocation of assets to the risk.

The risk parity approach asserts that when asset allocations are adjusted (leveraged or deleveraged) to the same risk level, risk parity is created resulting in more resistance to discontinuity events. The principles of risk parity will be applied differently according to the risk appetite, goals and objectives of the organization and can yield different results for each organization over time.

As a result of the globalized environment in which we operate today risks that were virtually unknown in the past decade continue to surface resulting in an increased need for organizations to constantly assess the global landscape to determine potential impacts (positive and negative) of risk realization.

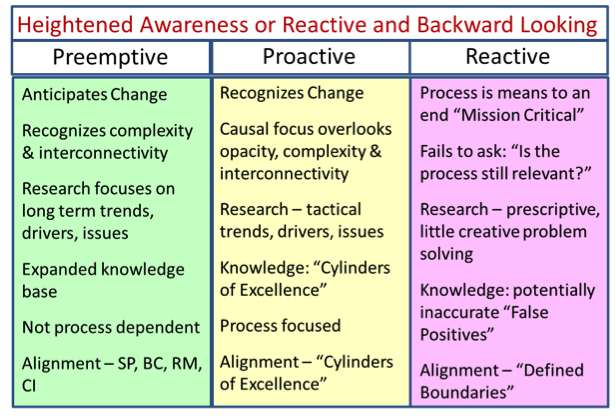

The table below presents three columns: Reactive, Proactive and Preemptive. Each column presents the characteristics that are exhibited within organizations that can be labeled “reactive”, “proactive” and “preemptive”. Please note that while all organizations would like to consider themselves to be preemptive, the majority find that they fall into the reactive column. However, becoming a preemptive organization is a worthwhile goal to seek.

Michael Kami, in his book “Trigger Points” suggests a 12 step process. I have modified the 12 steps to apply them to changing risk perceptions after an event. The 12 steps can be easily applied prior to an event materializing and can act as a guide to enhance the planning process. Here are the 12 steps:

- Step 1: Where Are We? Develop an External Environment Profile

What are the key factors in our external environment and how much can we control them?

- Step 2: Where Are We? Develop an Internal Environment Profile

Build detailed snapshots of your business activities as they are at present.

- Step 3: Where Are We Going? Develop Assumptions about the Future External Environment

Catalog future influences systematically; know your key challenges and threats.

- Step 4: Where Can We Go? Develop a Capabilities Profile

What are our strengths and needs? How are we doing in our key results and activities areas?

- Step 5: Where Might We Go? Develop Future Internal Environment Assumptions

Build assumptions, potentials, etc. Do not build predictions or forecasts! Assess what the future business situation might look like.

- Step 6: Where Do We Want to Go? Develop Objectives

Create a pyramid of objectives; redefine your business; set functional objectives.

- Step 7: What Do We Have to Do? Develop a Gap Analysis Profile

What will be the effect of new external forces? What assumptions can we make about future changes to our environment?

- Step 8: What Could We Do? Opportunities and Problems

Act to fill the gaps. Conduct an opportunity-problem feasibility analysis; risk analysis assessment; resource-requirements assessment. Build action program proposals.

- Step 9: What Should We Do? Select Strategy and Program Objectives

Classify strategy and program objectives; make explicit commitments; adjust objectives.

- Step 10: How Can We Do It? Implementation

Evaluate the impact of new programs.

- Step 11: How Are We Doing? Control

Monitor external environment. Analyze fiscal and physical variances. Conduct an overall assessment.

- Step 12: Change What’s not Working: Revise, Control, Remain Flexible

Revise strategy and program objectives as needed; revise explicit commitments as needed; adjust objectives as needed.

Conclusion

We must recognize that our perception of risk is altered by events as they occur and by their direct and indirect impact on us and our organizations. It is clear that bias and nonlinearity play an important role in risk perception and our ability to relate risk effects to our organization and ourselves. There are ten blind spots that we must overcome when assessing risk in a post-event environment. These are:

10 Blind Spots:

#1: Not Stopping to Think

#2: What You Don’t Know Can Hurt You

#3: Not Noticing

#4: Not Seeing Yourself

#5: My Side Bias

#6: Trapped by Categories

#7: Jumping to Conclusions

#8: Fuzzy Evidence

#9: Missing Hidden Causes

#10: Missing the Big Picture

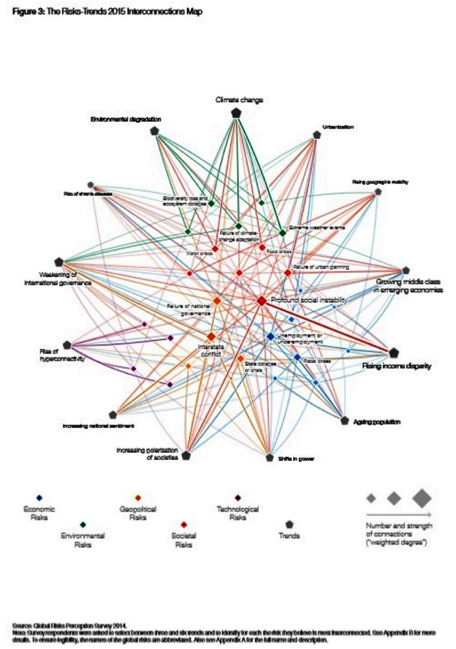

The recent World Economic Forum publication “Global Risks 2015” provides some excellent examples of connecting the dots. The figure (#3), entitled “The Risks-Trends 2015 Interconnections Map” from the WEF report is an example of what can be done when you connect the dots.

Risk taking is central to the functioning of any organization. Excessive risk taking and a simultaneous decline in the risk absorption capacity of the organization can lead to catastrophic results (i.e., the financial system and financial crisis). One can never achieve true certainty when assessing risk unless you reduce the probabilities to zero or one. Opacity, that is, constant uncertainty and changing factors makes getting a clear picture of risk realities nearly impossible. In order to overcome opacity you need to constantly monitor the risk environment. It’s all about targeted flexibility, the art of being prepared, rather than preparing for specific events. Being able to respond rather than being able to forecast, facilitates early warning and proactive response to shifts in your market segment.

We live in a world full of consequences. Our decisions need to be made with the most information available with the recognition that all decisions carry with them flaws due to our inability know everything. Our focus should be on how our flawed decisions establish a context for flawed risk assessments, leading to flawed plans, resulting in flawed abilities to execute effectively. If we change our thought processes from chasing symptoms and ignoring consequences to recognizing the limitations of decision making under uncertainty we may find that the decisions we are making have more upside than downside.

We’re limited not by the amount of risk we can identify, but by how inventive we are about how we think about risk and how much we’re willing to do to buffer against risk realization.

“If you keep doing what you’ve always done – you’ll keep getting what you’ve always gotten.” We need to change how we assess risk, if we do not do this, we can expect to continue to repeat the mistakes of the past.

About the Author

Geary Sikich – Entrepreneur, consultant, author and business lecturer

Contact Information: E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com. Telephone: 1- 219-922-7718.

Geary Sikich is a seasoned risk management professional who advises private and public sector executives to develop risk buffering strategies to protect their asset base. With a M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance, Geary’s focus is human capital: what people think, who they are, what they need and how they communicate. With over 25 years in management consulting as a trusted advisor, crisis manager, senior executive and educator, Geary brings unprecedented value to clients worldwide.

Geary is well-versed in contingency planning, risk management, human resource development, “war gaming,” as well as competitive intelligence, issues analysis, global strategy and identification of transparent vulnerabilities. Geary began his career as an officer in the U.S. Army after completing his BS in Criminology. As a thought leader, Geary leverages his skills in client attraction and the tools of LinkedIn, social media and publishing to help executives in decision analysis, strategy development and risk buffering. A well-known author, his books and articles are readily available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and the Internet.