We hear a lot about things that are being called “Black Swans” today thanks to Nassim Taleb and his extremely successful book, “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable,” now in its second edition. I have written several articles centering on the “Black Swan” phenomenon; defending, clarifying and analyzing the nature of “Black Swan” events. And, I am finding that wildly improbable events are becoming perfectly routine events.

We hear a lot about things that are being called “Black Swans” today thanks to Nassim Taleb and his extremely successful book, “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable,” now in its second edition. I have written several articles centering on the “Black Swan” phenomenon; defending, clarifying and analyzing the nature of “Black Swan” events. And, I am finding that wildly improbable events are becoming perfectly routine events.

What this means is that businesses and governments need to be even more vigilant in their prosecution of enterprise risk management initiatives. Private and Public Sector operations are complex and becoming more complex as more entrants to the global marketplace compete for fewer and fewer available resources at an ever quickening pace.

So, is society, as we know it, on the verge of collapse, destruction, another stone-age? Seems that you cannot turn on a television, radio or the plethora of personal communication devices available without headlines screaming at you about people with Molotov cocktails, car bombs, murders, floods, fires, car crashes, riots and, celebrities gone wrong. Sovereign nations are going bankrupt, sabers are being rattled; how you might ask, is it all going to end?

Question # 1: How much would you be willing to pay to eliminate a 1/2,500 chance of immediate death?

I ask this question as a simple way to get an understanding of where your perception of risk is coming from. Is it logical and rational or is it emotional and intuitive? Ponder the question as you read the rest of this piece.

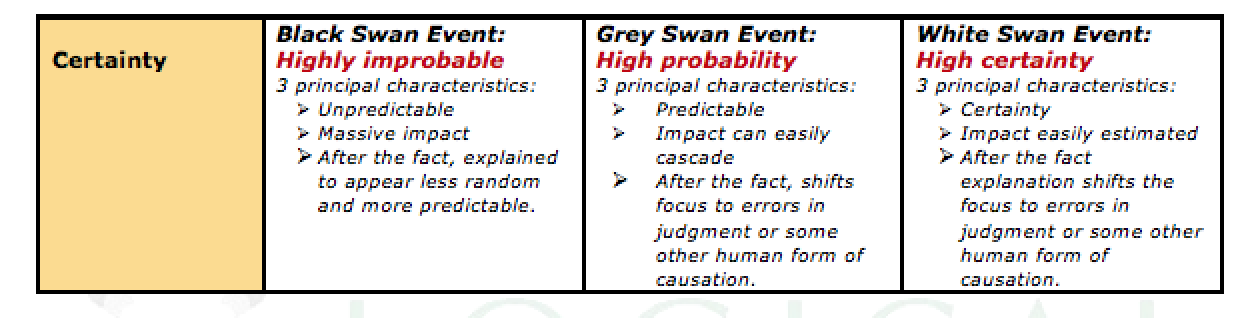

What exactly are all these swans and what do they mean?

Nassim Taleb provides the answer for one of the Swans in his book “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable.” He states that a Black Swan Event is:

A black swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.

Taleb continues by recognizing what he terms the problem –

“Lack of knowledge when it comes to rare events with serious consequences.”

The above definition and the recognized problem are cornerstones to the argument for a serious concern regarding how risk management is currently practiced. However, before we go too far in our discussion, let us define what the other two swans look like.

A grey swan is a highly probable event with three principal characteristics: it is predictable; it carries an impact that can easily cascade; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that recognizes the probability of occurrence, but shifts the focus to errors in judgment or some other human form of causation.

I suggest that we tend to phrase the problem thus –

“Lack of judgment when it comes to high probability events that have the potential to cascade.”

Now for the “White Swan”

A white swan is a highly certain event with three principal characteristics: it is certain; it carries an impact that can easily be estimated; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that recognizes the certainty of occurrence, but again, shifts the focus to errors in judgment or some other human form of causation.

I suggest that we tend to phrase the problem thus –

“Ineptness and incompetence when it comes to certainty events and their effects.”

The table below sums up the categorization of the three swan events.

Taleb uses the example of the recent financial crash as a “White Swan” event. In a video about risk and robustness, Taleb talks with James Surowiecki of the New Yorker, about the causes of the 2008 financial crisis and the future of the U.S. and by default the global economy. A link to the video follows: http://link.brightcove.com/services/player/bcpid1827871374?bctid=90038921001

More “White Swans” does not mean full speed ahead

Risk is complex. When risk is being explained, we often have difficulty listening and comprehending the words used in the explanation. Why? The rather simple explanation is: compelling stories are most often told with dramatic graphics! Molotov Cocktails, RPG-7’s and riots are interesting stuff to watch; no matter that the event has occurred elsewhere and may be totally meaningless to you. Is this pure drama or are these events that we should be concerned about? Or are they so unusual and rare that we fail to comprehend the message about the risks that we face?

Communication and how we communicate is a key factor. Words by themselves are about 7% effective as a communication tool. Words, when coupled with voice tonality raise effectiveness to about 38%. However, the most effective way to communicate is via physiology, which gets us to about 55% effective. Well, the next best thing to being there is being able to see what is there. Hence the effectiveness of graphics that evoke drama, physiology and raise emotions in communicating your message! The quote that a picture is worth a thousand words has never been so true as it is today.

Ideas get distorted in the transmission process. We typically remember:

- 10% what we hear

- 35% what we see

- 65% what we see & hear

Yet, we typically spend:

- 30% speaking

- 9% writing

- 16% reading

- 45% listening

We live in an era of information explosion and near instantaneous availability to this information. Driven by a media bias for the dramatic we are constantly being informed about some great calamity that has befallen mankind somewhere in the world. The BP disaster in the Gulf of Mexico has been eclipsed by flooding in Pakistan, which will get eclipsed by some other catastrophe.

Society is not awash with disasters! There is always another flood, riot, car bomb, murder, financial failure just around the corner. And, there is a compelling reason for this! The societies we live in have a lot of people! Some quick examples – China and India each have over 1 billion people. The U.S. has 300 million people. The European Union has 450 million people. Japan has 127 million people.

These numbers alone ensure that rare events (even very low probability events) will occur regularly; making the wildly improbable perfectly routine. This is true for countries worldwide. Population size is not a factor – Canada has 32 million people, Australia 20 million, the Netherlands 17 million and New Zealand 4 million. Take this to a smaller level – cities; and you find:

- Tokyo, Japan – 28,025,000

- Mexico City, Mexico – 18,131,000

- Mumbai, India – 18,042,000

- Sáo Paulo, Brazil – 17, 711,000

- New York City, USA – 16,626,000

- Shanghai, China – 14,173,000

- Lagos, Nigeria – 13,488,000

- Los Angeles, USA – 13,129,000

- Calcutta, India – 12,900,000

- Buenos Aires, Argentina – 12,431,000

The above may be the ten largest cities in the world; but, consider this – India has 192 cities with populations of over 200,000 people and China has 40 cities with populations of over 2,000,000. New York City with 8 million, London with 7.5 million, Toronto with 4.6 million and Chicago with 2.8 million barely would be of significance in China.

With this many people around, there would appear to be a bottomless supply of rare, but dramatic events to choose from. Does this seemingly endless parade of tragedy reflect an ever dangerous world? Or, are the risks overestimated due to the influence of skewed images?

Taleb tells us that the effect of a single observation, event or element plays a disproportionate role in decision-making creating estimation errors when projecting the severity of the consequences of the event. The depth of consequence and the breadth of consequence are underestimated resulting in surprise at the impact of the event. Theories fail most in the tails; some domains are more vulnerable to tail events.

Risk, Risk Perception, Risk Reality

When we see cooling towers, our frame of reference generally will go to nuclear power plants. More specifically, to Three Mile Island, where America experienced its closest scare as a result of a series of errors and misjudgments. As you can see a cooling tower is nothing more than a large vent that is designed to remove heat from water (what is termed “non-contact water) used to generate steam.

When we see cooling towers, our frame of reference generally will go to nuclear power plants. More specifically, to Three Mile Island, where America experienced its closest scare as a result of a series of errors and misjudgments. As you can see a cooling tower is nothing more than a large vent that is designed to remove heat from water (what is termed “non-contact water) used to generate steam.

We worry about cooling towers spewing forth radioactive plumes that will cause us death – when, in fact, this cannot happen. Yet we regularly board commercial airliners and entrust our lives to some of the most complex machinery man has created!

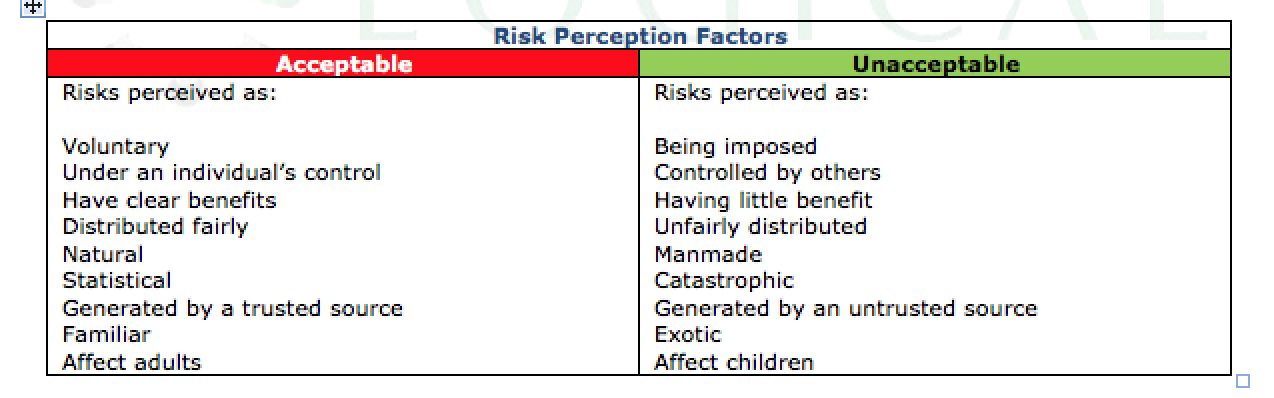

Our perceptions of risk are influenced by several factors. Peter Sandman, Paul Slovic and others have identified many factors that influence how we perceive risk. For example:

People perceive risks differently; people do not believe that all risks are of the same type, size or importance. These influencing factors affect how we identify, analyze and communicate risk. Why is it so important to effectively communicate risk information? Here are a few vivid examples of how poor communication/no communication turned risk realization into brand disasters:

- Firestone Tire Recall – Destroys a 100 year relationship with Ford

- Exxon Valdez Oil Spill – Still getting press coverage after 20 years

- Coke Belgium Contamination – Loss of trust

- BP Deepwater Horizon – Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) restructured?

Many years ago, I attended a conference on risk and risk communication in Chicago in the aftermath of the Bhopol disaster in India. Peter Sandman was one of the speakers and he left an indelible imprint on my brain that has stood the test of time and the test of validation. He drew the following equation:

RISK = HAZARD + OUTRAGE

Sandman, explained his equation as follows:

“Public perception of risk may not bear much resemblance to Risk Assessment. However, when it comes to their accepting risk one thing is certain; perception is reality.”

Sandman concluded his presentation with the following advice regarding the six interrogatories:

- WHO: Identify internal/external audiences

- WHAT: Determine the degree of complexity

- WHY: Work on solutions – not on finger pointing

- WHEN: Timing is critical

- WHERE: Choose your ground – know your turf

- HOW: Manner, method, effectiveness

In the 20+ years since that speech in Chicago much has changed. Social Media has, will, might; transform our lives – take your choice. While I agree that the Internet has transformed the lives of millions; I am not convinced that it has yet displaced the traditional media sources for our news.

One issue that is yet to be resolved is “how trustworthy the source.” For example, the following story appeared on the Internet:

US Orders Blackout Over North Korean Torpedoing Of Gulf Of Mexico Oil Rig

Source: EU TIMES – Posted on 1 May 2010

A grim report circulating in the Kremlin today written by Russia’s Northern Fleet is reporting that the United States has ordered a complete media blackout over North Korea’s torpedoing of the giant Deepwater Horizon oil platform owned by the World’s largest offshore drilling contractor Transocean that was built and financed by South Korea’s Hyundai Heavy Industries Co. Ltd., that has caused great loss of life, untold billions in economic damage to the South Korean economy, and an environmental catastrophe to the United States.

To the reason for North Korea attacking the Deepwater Horizon, these reports say, was to present US President Obama with an “impossible dilemma” prior to the opening of the United Nations Review Conference of the Parties to the Treat on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) set to begin May 3rd in New York.

For the complete story see link: http://www.linkedin.com/news?viewArticle=&articleID=126102399&gid=2086769&srchCat=WOTC&articleURL=http%3A%2F%2Fwww%2Eeutimes%2Enet%2F2010%2F05%2Fus-orders-blackout-over-north-korean-torpedoing-of-gulf-of-mexico-oil-rig%2F&urlhash=76of

Twittering fingers want to know! Could the story above be true? The posting received 245 comments and a rating of 3.9 on a scale of 5 based on 204 votes. Assuming a rating of 5 equals totally believable, the rating of 3.9 indicates that the story was believed by many – thank you social media!

Information, especially information found via social networking, social media, etc., requires significant insight and analysis. Beyond that, confirmation of the source is critical. Can you imagine the above story making its way into the legal proceedings under discovery?

Now in its second year, the Digital Influence Index created by the public relations firm, Fleishman-Hillard Inc. covers roughly 48% of the global online population, spanning France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, China, Japan, and the United States. With less than 50% coverage (62% of the global online population is not reflected in the Digital Influence Index) they would have you believe that the index is a valid indicator of the ways in which the Internet is impacting the lives of consumers.

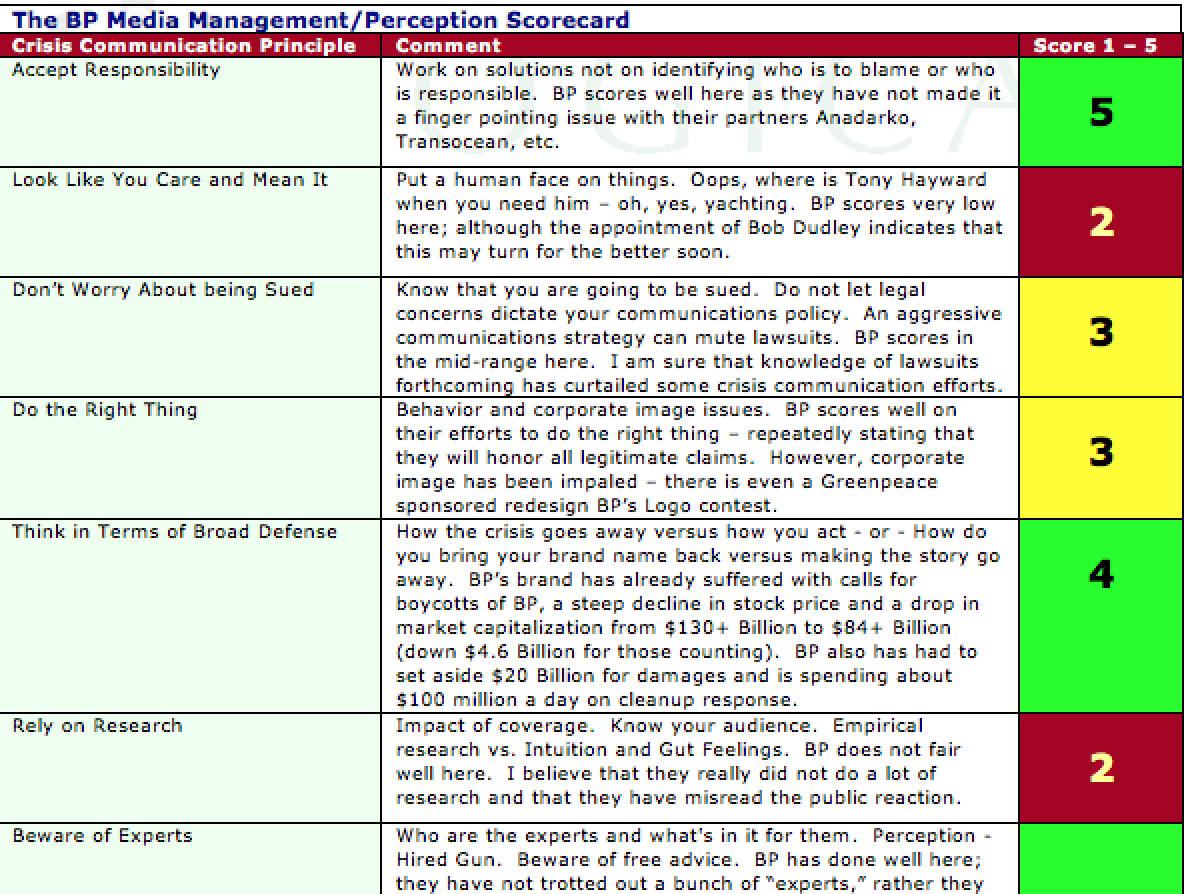

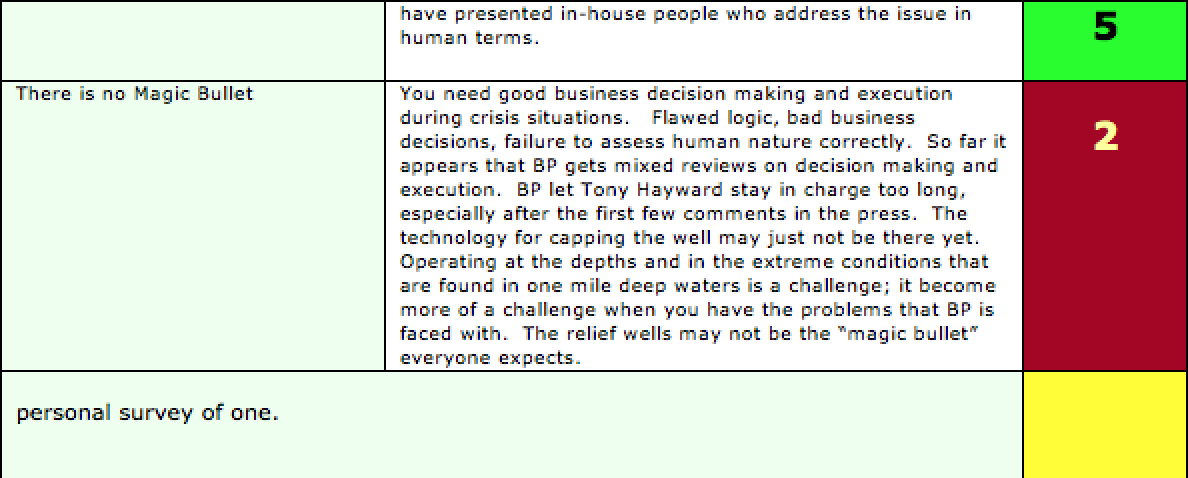

While BP has been an easy target for the media, it is far from clear that BP’s handling of the Deepwater Horizon event has been as bad as portrayed. Many years ago I was provided with some insight as I developed a crisis communications program for another major oil company. While attending a presentation on crisis communications eight guiding principles were offered. I think that they are still very valid today:

| ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY | THINK IN TERMS OF BROAD DEFENSE |

| LOOK LIKE YOU CARE AND MEAN IT | RELY ON RESEARCH |

| DON’T WORRY ABOUT BEING SUED | BEWARE OF EXPERTS |

| DO THE RIGHT THING | THERE IS NO MAGIC BULLET |

So, what, hypothetically, does BP’s Scorecard look like? Is it balanced, askew, Misaligned, or just much maligned? On a scale of 1 – 10, with 1 being dreadful and 5 being Excellent Let’s take a look at how BP has done thus far:

Management is never put more strongly to the test than in a crisis situation. The objectives are immediate and so are the results. A crisis is an event requiring rapid decisions involving the media that, if handled incorrectly, could damage your company’s credibility and reputation.

Risk perception will influence your ERM program. Management simply must devote sufficient resources to recognizing and understanding how operations are being viewed from a risk perspective. With routine incidents being treated as front‑page news by the media, you must be prepared to deal with public perception, as well as reality.

Disruptive (Unsettling) by Design (with Purpose, Plan, Intent)

How can you get better at anticipating what will happen? That is the million dollar question. What do you need to do to create an ERM program that leverages forward and creates global awareness within your organization? You must learn to create a mosaic from diverse sources of information and diverse elements within your enterprise. You must learn how to respond to change, disruption and uncertainty; and how to use disruption and uncertainty to your advantage to create a business continuity plan that is truly resilient. Disruption is transforming the way smart organizations make decisions, keeping their business in business when faced with disruptive events. For example, here might be a typical sequence of events:

A risk materializes or is realized (event occurs). Someone, who is perceived to have good information and/or insight into the event or problem, makes a decision. Others observing the first person’s decision avoid further analysis/discovery and copy the earlier decision. The more people that copy the earlier decision, the less likely any new discovery or analysis will occur. If the earliest decision was correct, everything works out. If it was not, the error is compounded, literally cascading throughout the organization.

Modern communications systems allow information to cascade rapidly; exacerbating the effect of a wrong or inadequate decision. Disruption happens. Natural disasters, technology disasters, manmade disasters happen. How would a technology breakthrough, a shift in consumer demand or a rise, or fall, in a critical market affect the continuity of your business? Any of these can rewrite the future of a company – or a whole industry. If you haven’t faced this moment, you may soon. It’s time to change the way you think about continuity and the way you run your business.

How you decide to respond is what separates the leaders from the left behind. Today’s smartest executives know that disruption is constant and inevitable. They’ve learned to absorb the shockwaves that change brings and can use that energy to transform their companies and their careers

Imagine that your ERM program has been implemented as it was designed. You and your organization carried out ERM implementation following every detail contained in the policy, planning documents and applicable protocols. Your ERM program has failed. That is all you know. Your ERM program failed.

Now your challenge and that of your ERM team is to explain why they think that the ERM program failed. You must determine how much contrary evidence (information) was explained away based on the theory that the ERM program you developed will succeed if you implement the steps required to identify and respond to risks to your business operations.

The goal of this type of exercise is to break the emotional attachment to the success of the ERM program. When we create an ERM program we become emotionally attached to its success. By showing the likely sources of breakdown that will impede and/or negate the ERM program (failure), we utilize a methodology that allows us to conduct a validation of the ERM program by determining the potential failure points that are not readily apparent in typical exercise processes.

ERM programs are based on a set of background assumptions that are made consciously and unconsciously. Risk materializes and seemingly without warning, quickly destroys those assumptions. The ERM program is viewed as not good and in need of complete overhaul. The collapse of assumptions is not the only factor or prominent feature that defines failure point exercise methodology; but it is without doubt, one of the most important.

Decision scenarios allow us to describe forces that are operating to enable the use of judgment by the participants. The Failure Point Methodology, developed by Logical Management Systems, Corp., allows you to identify, define and assess the dependencies and assumptions that were made in developing the ERM program. This methodology facilitates a non-biased and critical analysis of the ERM program that allows planners and the ERM Team to better understand the limitations that they may face when implementing and maintaining the program.

Developing the exercise scenario for the Failure Point Methodology is predicated on coherence, completeness, plausibility and consistency. It is recognized at the beginning of the scenario that the ERM program has failed. It is therefore not really necessary to create an elaborate scenario describing catastrophic events in great detail. The participants can identify trigger points that could create a reason for the ERM program to fail. This methodology allows for maximizing the creativity of the ERM Team in listing why the program has failed and how to overcome the failure points that have been identified.

This also is a good secondary method for ensuring that the ERM Team is trained on how the program works and that they have read and digested the information contained in the program documentation.

As it is often the case that the developers are not the primary and/or secondary decision makers within the program; and that the primary decision makers within the program often have limited input during the creation of the program (time limited interviews, response to questionnaires, etc.).

This type of exercise immerses the participants in creative thought generation as to why the ERM program failed. It also provides emphasis for ownership and greater participation in developing the ERM program. Senior management and boards can benefit from periodically participating in Failure Point exercises; one output being the creation of and discussion about thematic risk maps. As a result of globalization, there is no such thing as a “typical” failure or a “typical” success. The benefits of Failure Point exercises should be readily apparent. You can use the exercise process to identify the unlikely but potentially most devastating risks your organization faces. You can build a monitoring and assessment capability to determine if these risks are materializing. You can also build buffers that prevent these risks from materializing and/or minimize their impact should the risk materialize.

Managing “White Swans” – Dealing with Certainty

There are two areas that need to be addressed for Enterprise Risk Management programs to be successful. Both deal with “White Swans” (certainty). The first is overcoming “False Positives” and the second is overcoming “Activity Traps.”

A “False Positive” is created when we ask a question and get an answer that appears to answer the question. In an article, entitled Disaster Preparedness, featured in CSO Magazine written by Jon Surmacz August 14, 2003, it was written that:

“two-thirds (67 percent) of Fortune 1000 executives say their companies are more prepared now than before 9/11 to access critical data in a disaster situation.”

The article continued:

“The majority, (60 percent) say they have a command team in place to maintain information continuity operations from a remote location if a disaster occurs. Close to three quarters of executives (71 percent) discuss disaster policies and procedures at executive-level meetings, and 62 percent have increased their budgets for preventing loss of information availability.”

source Harris Interactive

Better prepared? The question is for what? To access information – yes, but not to address human capital, facilities, business operations, etc. – hence a false positive was created.

“Processes and procedures are developed to achieve an objective (usually in support of a strategic objective). Over time goals and objectives change to reflect changes in the market and new opportunities. However, the processes and procedures continue on. Eventually, procedures become a goal in themselves – doing an activity for the sake of the activity rather than what it accomplishes.”

To overcome the effect of “False Positives” and “Activity Traps” the following section offers some thoughts for consideration.

12 steps to get from here to there and temper the impact of all these swans

Michael J. Kami author of the book, ‘Trigger Points: how to make decisions three times faster,’ wrote that an increased rate of knowledge creates increased unpredictability. Stanley Davis and Christopher Meyer, authors of the book ‘Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy,’ cite ‘speed – connectivity – intangibles’ as key driving forces. If we take these points in the context of the black swan as defined by Taleb we see that our increasingly complex systems (globalized economy, etc.) are at risk. Kami outlines 12 steps in his book that provide some useful insight. How you apply them to your enterprise can possibly lead to a greater ability to temper the impact of all these swans.

Step 1: Where Are We? Develop an External Environment Profile

Key focal point: What are the key factors in our external environment and how much can we control them?

Step 2: Where Are We? Develop an Internal Environment Profile

Key focal point: Build detailed snapshots of your business activities as they are at present.

Step 3: Where Are We Going? Develop Assumptions about the Future External Environment

Key focal point: Catalog future influences systematically; know your key challenges and threats.

Step 4: Where Can We Go? Develop a Capabilities Profile

Key focal point: What are our strengths and needs? How are we doing in our key results and activities areas?

Step 5: Where Might We Go? Develop Future Internal Environment Assumptions

Key focal point: Build assumptions, potentials, etc. Do not build predictions or forecasts! Assess what the future business situation might look like.

Step 6: Where Do We Want to Go? Develop Objectives

Key focal point: Create a pyramid of objectives; redefine your business; set functional objectives.

Step 7: What Do We Have to Do? Develop a Gap Analysis Profile

Key focal point: What will be the effect of new external forces? What assumptions can we make about future changes to our environment?

Step 8: What Could We Do? Opportunities and Problems

Key focal point: Act to fill the gaps. Conduct an opportunity-problem feasibility analysis; risk analysis assessment; resource-requirements assessment. Build action program proposals.

Step 9: What Should We Do? Select Strategy and Program Objectives

Key focal point: Classify strategy and program objectives; make explicit commitments; adjust objectives.

Step 10: How Can We Do It? Implementation

Key focal point: Evaluate the impact of new programs.

Step 11: How Are We Doing? Control

Key focal point: Monitor external environment. Analyze fiscal and physical variances. Conduct an overall assessment.

Step 12: Change What’s not Working Revise, Control, Remain Flexible

Key focal point: Revise strategy and program objectives as needed; revise explicit commitments as needed; adjust objectives as needed.

I would add the following comments to Kami’s 12 points and the Davis, Meyer point on speed, connectivity, and intangibles. Understanding the complexity of the event can facilitate the ability of the organization to adapt if it can broaden its strategic approach. Within the context of complexity, touchpoints that are not recognized create potential chaos for an enterprise and for complex systems. Positive and negative feedback systems need to be observed/acted on promptly. The biggest single threat to an enterprise will be staying with a previously successful business model too long and not being able to adapt to the fluidity of situations (i.e., black swans). The failure to recognize weak cause-and-effect linkages, small and isolated changes can have huge impacts. Complexity (ever growing) will make the strategic challenge more urgent for strategists, planners and CEOs.

Taleb offers the following two definitions: The first is for ‘Mediocristan’; a domain dominated by the mediocre, with few extreme successes or failures. In Mediocristan no single observation can meaningfully affect the aggregate. In Mediocristan the present is being described and the future forecasted through heavy reliance on past historical information. There is a heavy dependence on independent probabilities.

The second is for ‘Extremeistan’; a domain where the total can be conceivably impacted by a single observation. In Extremeistan it is recognized that the most important events by far cannot be predicted; therefore there is less dependence on theory. Extremeistan is focused on conditional probabilities. Rare events must always be unexpected, otherwise they would not occur and they would not be rare.

When faced with the unexpected presence of the unexpected, normality believers (Mediocristanians) will tremble and exacerbate the downfall. Common sense dictates that reliance on the record of the past (history) as a tool to forecast the future is not very useful. You will never be able to capture all the variables that affect decision making. We forget that there is something new in the picture that distorts everything so much that it makes past references useless. Put simply, today we face asymmetric threats (black swans and white swans) that can include the use of surprise in all its operational and strategic dimensions and the introduction of and use of products/services in ways unplanned by your organization and the markets that you serve. Asymmetric threats (not fighting fair) also include the prospect of an opponent designing a strategy that fundamentally alters the market that you operate in.

Summary Points

I will offer the following summary points:

- Clearly defined rules for the world do not exist, therefore computing future risks can only be accomplished if one knows future uncertainty

- Enterprise Risk Management needs to expand to effectively identify and monitor potential threats, hazards, risks, vulnerabilities, contingencies and their consequences

- The biggest single threat to business is staying with a previously successful business model too long and not being able to adapt to the fluidity of the situation

- Current risk management techniques are asking the wrong questions precisely; and we are getting the wrong answers precisely; the result is the creation of false positives

- Risk must be viewed as an interactive combination of elements that are linked, not solely to probability or vulnerability, but to factors that may be seemingly unrelated.

- This requires that you create a risk mosaic that can be viewed and evaluated by disciplines within the organization in order to create a product that is meaningful to the entire organization, not just to specific disciplines with limited or narrow value.

- The resulting convergence assessment allows the organization to categorize risk with greater clarity allowing decision makers to consider multiple risk factors with potential for convergence in the overall decision making process.

- Mitigating (addressing) risk does not necessarily mean that the risk is gone; it means that risk is assessed, quantified, valued, transformed (what does it mean to the organization) and constantly monitored.

Unpredictability is fast becoming our new normal. Addressing unpredictability requires that we change how Enterprise Risk Management programs operate. Rigid forecasts that cannot be changed without reputational damage need to be put in the historical dust bin. Forecasts often times are based on a “static” moment; frozen in time, so to speak. Often times, forecasts are based on a very complex series of events occurring at precise moments. Assumptions on the other hand, depend on situational analysis and the ongoing tweaking via assessment of new information. An assumption can be changed and adjusted as new information becomes available. Assumptions are flexible and less damaging to the reputation of the organization.

Recognize too, that unpredictability can be positive or negative. For example; our increasing rate of knowledge creates increased unpredictability due to the speed at which knowledge can create change.

Conclusion

I started this piece with a question and I will end it with a question. The question is similar to the question at the beginning of this piece.

Question # 2: How much would you have to be paid to accept a 1/2,500 chance of immediate death?

A few minor changes in the phrasing of the questions, changes your perception of the risk and, most probably, your assessment of your value. You will generally place a greater value on what it takes to accept a risk rather than on what you are willing to pay to take a risk.

You may recall the wording of the question; if not here it is again:

Question # 1: How much would you be willing to pay to eliminate a 1/2,500 chance of immediate death?

Yet, you pay to take a risk every time you fly! And, on average, you pay $400 – $500 per flight. Daily takeoffs and landings at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago average of 2,409 per day. Daily takeoffs and landings at Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta average of 2,658 per day. This amounts to a lot of people willing to take a substantial risk – taking off and landing safely. The degree of risk is based on the perception of the person regarding their vulnerability to the consequences of the risk that is being posited materializing. Risk is, therefore, never absolute. Risk is set by the receiver of the consequences.

Bio:

Geary Sikich

Entrepreneur, consultant, author and business lecturer

E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com

Telephone: (219) 922-7718

Geary Sikich is a Principal with Logical Management Systems, Corp., a consulting and executive education firm with a focus on enterprise risk management and issues analysis; the firm’s web site is www.logicalmanagement.com. Geary is also engaged in the development and financing of private placement offerings in the alternative energy sector (biofuels, etc.), multi-media entertainment and advertising technology and food products. Geary developed LMSCARVERtm the “Active Analysis” framework, which directly links key value drivers to operating processes and activities. LMSCARVERtm provides a framework that enables a progressive approach to business planning, scenario planning, performance assessment and goal setting.

Prior to founding Logical Management Systems, Corp. in 1985 Geary held a number of senior operational management positions in a variety of industry sectors. Geary served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army; responsible for the initial concept design and testing of the U.S. Army’s National Training Center and other intelligence related activities. Geary holds a M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance from the University of Texas at El Paso and a B.S. in Criminology from Indiana State University.

Geary is also an Adjunct Professor at Norwich University, where he teaches Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) and contingency planning electives in the MSBC program, including “Value Chain” Continuity, Pandemic Planning and Strategic Risk Management. He is presently active in Executive Education, where he has developed and delivered courses in enterprise risk management, contingency planning, performance management and analytics. Geary is a frequent speaker on business continuity issues business performance management. He is the author of over 200 published articles and four books, his latest being “Protecting Your Business in Pandemic,” published in June 2008 (available on Amazon.com).

Geary is a frequent speaker on high profile continuity issues, having developed and validated over 2,000 plans and conducted over 250 seminars and workshops worldwide for over 100 clients in energy, chemical, transportation, government, healthcare, technology, manufacturing, heavy industry, utilities, legal & insurance, banking & finance, security services, institutions and management advisory specialty firms. Geary consults on a regular basis with companies worldwide on business-continuity and crisis management issues.