The BP Deepwater Horizon catastrophe cast a shadow on the oil industry and its senior executives. Has the industry learned its lessons or will it be forced to repeat the same mistakes over and over again? Oil company executives and board members should have seen the Deepwater Horizon event is as a wake-up call for the industry.

Private and Public Sector operations are complex and becoming more complex as more entrants to the global marketplace compete for fewer and fewer available resources at an ever quickening pace. Since the Deepwater Horizon event there have been several incidents involving drilling platforms offshore. Offshore projects in Venezuela, Brazil, Nigeria, Russia and Britain have all experienced incidents that have led to loss of drilling and production platforms, releases of hydrocarbons and pollution.

The inevitable backlash of well meaning, but potentially ill conceived, regulations that have emerged since the Deepwater Horizon have largely been overlooked by the public and industry as we are caught up in the whirlwind of an economic crisis that threatens worldwide financial stability and nation states existence in some instances. From a regulatory standpoint, however, regulators are constantly in a reactive mode; creating regulations after the fact, that have either no “teeth,” or that fail to get implemented properly, or that over time are essentially dismissed.

Resource scarcity and Infrastructure vulnerability has become a front-and-center issue for national security and defense thinkers. These challenges, from water deficiency to the lack of reliable electricity, were once primarily managed by private sector enterprises, municipalities and cooperatives. Today infrastructure and resource management are at the intersection of private and public sector development and are key to our national security. Will future national security directives more effectively address the challenges of stabilizing our infrastructure and securing our access to critical resources? How will failed states (i.e., Libya, Iraq, Greece, Spain, etc.) affect our national security initiatives? How can governments, social entrepreneurs and the private sector work together to confront these new and mounting security challenges?

What are we learning about critical infrastructure protection and resilience as a result of recent global events such as Hurricane Sandy, the Japan earthquake/tsunami, etc.? How can this knowledge help your organization grow and remain resilient to natural and man-made disasters? How can this knowledge advance public sector initiatives regarding national security, resilient infrastructure and sustaining critical resources? What is the impact on current emergency response, management, recovery and restoration practices?

The efficient operation of public and private sector operations and their “value chains” (supply chain – customer) depend on a complex network of touchpoints. The interaction of these touchpoints often result in a “single point of failure” that can be transparent to those depending on them to work efficiently. Assessment and mitigation (“risk buffering”) strategies are critical to national security. Have we learned the lessons from recent events or are we destined to repeat our mistakes again and again?

- Ability to Identify and Manage Risk

Risk; business leaders know it exists. However, oftentimes companies aren’t taking a holistic approach to assess and manage their risk exposures. Disruption happens. Natural disasters, technology disasters, manmade disasters happen.

Oil companies entered the deep waters of the gulf armed with technology that works and generally works well. How did technology fail them? The failure is not in the technology it is in the unanticipated difficulties that are encountered when drilling at depths that are relatively unfamiliar to the industry.

Could a technology breakthrough have changed what occurred to the Deepwater Horizon? Will there be a shift in consumer demand or a rise, or fall, in the price of oil that affects critical markets? Any of these can rewrite the future of a company – or a whole industry. If you haven’t faced this moment, you may soon. It’s time that oil company executives change the way they think about enterprise risk management, continuity of business operations and the way they run their businesses.

Because a splintered approach to enterprise risk management has been the norm, with silos of risk management within organizations, the result has been that risk is poorly defined and buffering the organization from risk realization is; pardon the pun, risky at best. Taking enterprise risk management on with a truly integrated head-on approach is necessary.

Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) is defined by many different groups in a variety of ways. Each group has a vested interest in their view of what ERM constitutes. Risk and non-risk management professionals are so enmeshed in following risk management protocols promulgated by financial and non-financial regulatory and oversight entities that they cannot see risk for what it really is. They get caught in the “Activity Trap.”

Many view “Mitigation” as a panacea, thinking that once mitigated risk does not have to be worried about. This false premise creates a reaction time gap. Practitioners can only hope that they are buying their enterprises sufficient reaction time, when in fact, they should be asking, “how much reaction time are we losing because our ERM program is fragmented and fails to understand risk throughout the enterprise?”

The greatest failure of most enterprise risk management programs is that they cannot de-center. That is, they cannot see the risk from different perspectives internally or externally. Poor or no situation awareness generates a lack of expectancies, resulting in inadequate preparation for the future.

- Corporate Governance, Enterprise Risk Management and Compliance

Corporate Governance has traditionally defined the ways that a firm safeguards the interests of its financiers (investors, lenders, and creditors). Governance provides a framework of rules and practices for a board of directors to ensure accountability, fairness and transparency in a firm’s relationship with all stakeholders (financiers, customers, management, employees, government and the community).

The governance framework generally consists of explicit and implicit contracts between the firm and the stakeholders for distribution of responsibilities, rights and rewards; secondly it establishes procedures for reconciling the sometimes conflicting interests of stakeholders in accordance with their duties, privileges, and roles and third, it establishes procedures for proper supervision, control, and information-flows to serve as a system of checks-and-balances.

The failure to identify and manage the risks present in the energy industry will have a cascade effect, creating reputational damage (either real and/or perceived). The industry is faced with several issues that are transparent to many. A heavy dependence on performing processes that become activity traps creates an inability to change and/or even recognize the need for change. In his book entitled, “Management and the Activity Trap,” George Odiorne concludes that activity traps are created when:

Processes and procedures are developed to achieve an objective (usually in support of a strategic objective).

Over time goals and objectives change to reflect changes in the market and new opportunities. However, the processes and procedures continue on.

Eventually, procedures become a goal in themselves – doing an activity for the sake of the activity rather than what it accomplishes.

- Edwards Deming created 14 principles for management. Deming recognized the folly in working for the sake of procedure rather that finding the goal and making every effort to achieve it. We know now what to measure, we know the current performance and we have discovered some problem areas. Now we have to understand why problems are generated, and what the causes for these problems are; however, as I stated in a speech given in 2003 “because we are asking the wrong questions precisely, we are getting the wrong answers precisely; and as a result we are creating false positives.”

Nassim Taleb, author of the best seller, “The Black Swan,” has stated that “we lack of knowledge when it comes to rare events with serious consequences. The effect of a single observation, event or element plays a disproportionate role in decision-making creating estimation errors when projecting the severity of the consequences of the event. The depth of consequence and the breadth of consequence are underestimated resulting in surprise at the impact of the event.”

While BP continues to be an easy target for those who see risk as something that can be eliminated, it is far from clear that BP’s risk management framework, to the extent it is evidenced in public documents, is any different other oil companies.

The oil industry is faced with risk issues that go well beyond fraudulent financial reporting. Greater recognition that operational risks can be the root cause of corporate failure is now becoming apparent. BP is not alone in its failure in the gulf. Toyota, Ford, Firestone, PDVSA (Venezuela’s State Oil Company), all have given us horrible examples of operational failure. While these have been less tragic than the gulf spill, more are certain to come.

The oil and gas business is inherently risky. Tony Hayward’s recent statement in BP’s annual report (2009) reflects the recognition of risk.

“Risk remains a key issue for every business, but at BP it is fundamental to what we do. We operate at the frontiers of the energy industry, in an environment where attitude to risk is key. The countries we work in, the technical and physical challenges we take on and the investments we make – these all demand a sharp focus on how we manage risk.”

In spite of all its efforts to manage risk, BP had more than its share of operational incidents from the explosion at its former Texas City refinery to a temporary shut down of Prudhoe Bay production. Is BP just unlucky? Or has the oil industry become so susceptible to the “Activity Trap” by relying on generally accepted risk management practices that may not work in today’s environment? What seems abundantly clear is that there is a large and ever growing gap in the ability of large global corporations to identify, alter and manage operational risks.

While the board of directors of most companies correctly place reliance on assurance providers and executives, it is increasingly clear that it may not be possible to “audit” our way to better operational risk. A new model of enterprise risk management is essential. And, while risk management technology may be available; dependence on its output should never become the cornerstone of enterprise risk management.

- The future of U.S. Energy Security – National Security at Risk?

We are faced with and aging infrastructure that is highly dependent on foreign sources of raw materials and finished products; with an aging workforce, slow uptake on alternatives; and increasing demand from growing markets for the resources that we have traditionally viewed as an extension of our domestic supply. Originally built in America it has sustained the United States for over a century:

- Now we are heavily dependent on foreign manufacturers to produce the products once made domestically in order to keep it running

- No Nuclear Plants since the 1970’s

- No New Refineries since Garyville, Louisiana, 1976

- Increasingly “single point of failure” vulnerability

- Long lead times to repair/replace

America used to export to the world, now it depends on the world for larger and larger percentages of the products it consumes:

- Net imports of crude oil in 2007 accounted for 58% of U.S. and steadily increases

- S. production declining since the 1970’s

- Critical components of the electric grid are built overseas (transformers, electronic components, etc.)

- Increasingly vulnerability to supply disruption

- In less than 3 years there’s expected to be a 30% to 40% shortage of technical and professional oil workers in the U.S., according to Damon Beyer of Katzenbach Partners, of Houston. As much as 80% of the workforce will be eligible for retirement in the next decade.

- In less than 5 years, just as the nuclear industry hopes to launch a renaissance, up to 19,600 nuclear workers – 35% of the workforce – will reach retirement age.

- The top 25 oil companies in the industry have shed more than one million employees since 1982.

- According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, more than 25% of the working population will reach retirement age by 2010, resulting in a potential worker shortage of nearly 10 million.

- America has no single point for coordination of a national plan to address energy sector needs. Federal, State and Local mandates serve to confuse and mislead.

If the above points hold true, we can expect more operational failures potentially of catastrophic magnitude. One could argue that we are already seeing more catastrophic operational risk failures.

Joseph Tainter, in his book, “The Collapse of Complex Societies,” states that “complex societies break down when increasing complexity results in negative marginal returns.” Have we created an unsustainably high level of complexity in our modern globally interconnected world? Will this interconnectivity and dependency on foreign sources to sustain our lifestyles lead to dire consequences for the U.S.?

- Are we flying behind the plane when it comes to Enterprise Risk Management or are there Black Swans everywhere?

There seem to be a lot of sightings of “Black Swans” lately. Should we be concerned or are we wishfully thinking, caught up in media hype; or are we misinterpreting what a “Black Swan” event really is? The term “Black Swan” has become a popular buzzword for many; including, contingency planners, risk managers and consultants. However, are there really that many occurrences that qualify to meet the requirement of being termed a “Black Swan” or are we just caught up in the popularity of the moment? The definition of a Black Swan according to Nassim Taleb, author of the book “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable” is:

A black swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.

There was a great deal of intense media focus (crisis of the moment) on the eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull and the recent Deepwater Horizon catastrophe. Note that less attention was paid by the media to a subsequent sinking of the Aban Pearl, an offshore platform in Venezuela that occurred on 13 May 2010 and events in Nigeria, Russia, Brazil and the North Sea.

Some have classified the recent eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull and the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe as Black Swan events. If these are Black Swans, then shouldn’t we classify the Aban Pearl also a Black Swan? Or is the Aban Pearl not a Black Swan because it did not get the media attention that the Deepwater Horizon has been receiving?

Please note also that Taleb’s definition of a Black Swan consists of three elements:

“it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random”

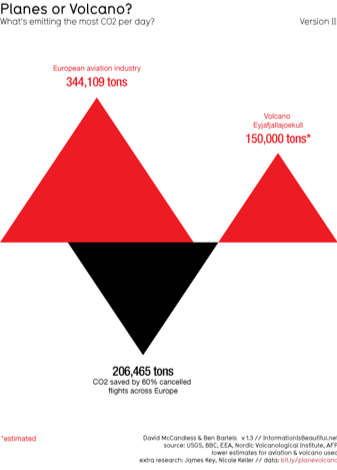

While the above cited events have met some of the criteria for a “Black Swan” – unpredictability; the massive impact of each is yet to be determined and we have yet to see explanations that make these events appear less random. Interestingly, the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull may qualify as a “White Swan” according to Taleb in his latest version of “The Black Swan” recently published. Eyjafjallajokull on 20 April 2010 (the date of the Deepwater Horizon event) was emitting between “150,000 and 300,000″ tons of CO2 a day. This contrasted with the airline industry emissions of almost 345,000 tons, according to an article entitled, “Planes or Volcano?” originally published on 16 April 2010 and updated on 20 April 2010 (http://bit.ly/planevolcano).

While we can only estimate the long term impact of the Deepwater Horizon event; the Aban Pearl according to statements by Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, appears to have resulted in no environmental release or loss of life.

Venezuela’s energy and oil minister, Rafael Ramirez, said there had been a problem with the flotation system of the semi-submersible platform, causing it to keel over and sink. Ramirez also said a tube connecting the rig to the gas field had been disconnected and safety valves activated, so there no risk of any gas leak. The incident came less than a month after an explosion that destroyed the Deepwater Horizon rig in the Gulf of Mexico. At the time of this writing oil prices are actually declining instead of rising as would be the expected outcome of a Black Swan event (perhaps we should rethink Deepwater Horizon and Aban Pearl and classify them as “White Swan” events?). What may be perceived as or classified as a Black Swan by the media driven hype that dominates the general populace may, in fact, not be a Black Swan at all for a minority of key decision makers, executives and involved parties. This poses a significant challenge for planners, strategists and CEO’s.

I would not necessarily classify the recent eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull and the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe or the Aban Pearl sinking as Black Swan events although their impact (yet to be fully determined) may be far reaching.

These events were not unexpected – the volcano existed and has erupted before and offshore rigs have exploded and sunk before (i.e., Piper Alpha 6 July 1988, killing 168 and costing $1,270,000,000.00). The three events cited do have Black Swan qualities when viewed in context to today’s complex global environment. This I believe is the Strategist, Planner and CEO’s greatest challenge – to develop strategies that are flexible enough to adapt to unforeseen circumstances while meeting corporate goals and objectives. This requires a rethinking of contingency planning, competitive intelligence activities and cross-functional relationships internally and externally.

- Conclusion

It takes over 85 million barrels of oil per day globally, as well as millions of tons of coal and billions of cubic feet of natural gas to enable modern society to operate as it does. In 2009 there were 214 vessels attacked, resulting in 47 hijackings and $120 million in ransoms paid for those ships were realized by the pirates. Since then, piracy has expanded to other areas – Nigeria, the Malacca Straits as examples. As gaps in the global network open up, guerrilla entrepreneurship is sure to follow.

I stated earlier that, “because we are asking the wrong questions precisely, we are getting the wrong answers precisely; and as a result we are creating false positives.” Unless we change the paradigm of enterprise risk management, we will continue to get false positives and find ourselves reacting to events instead of managing events effectively.

Unpredictability is the new normal. Rigid forecasts, cast in stone, cannot be changed without reputational damage; therefore strategists, planners and CEO’s are better served to make assumptions – an assumption can be changed, adjusted – assumptions are flexible and less damaging to an enterprise’s (or person’s) reputation. Unpredictability can be positive or negative. Never under estimate the impact of change (we live in a rapidly changing, interconnected world), inflation (this is not just monetary inflation, it includes the inflated impact of improbable events), opportunity (recognize the “White Swan” effect) and the ultimate consumer (most often overlooked in contingency plans is the effect of loss of customers).

Some final thoughts:

- If your organization is content with reacting to events it may not fair well

- Innovative, aggressive thinking is one key to surviving

- Recognition that theory is limited in usefulness is a key driving force

- Strategically nimble organizations will benefit

- Constantly question assumptions about what is “normal”

Lord John Browne, former Group Chief Executive of BP, sums it up well:

“Giving up the illusion that you can predict the future is a very liberating moment. All you can do is give yourself the capacity to respond to the only certainty in life – which is uncertainty. The creation of that capability is the purpose of strategy.”

In a crisis you get one chance – your first and last. Being lucky does not mean that you are good. You may manage threats for a while. However, luck runs out eventually; and panic, chaos, confusion set in, eventually leading to collapse.

How you decide to respond is what separates the leaders from the left behind. Today’s smartest executives know that disruption is constant and inevitable. They’ve learned to absorb the shockwaves that change brings and can use that energy to transform their companies and their careers.

BIO:

Geary Sikich

Entrepreneur, consultant, author and business lecturer

Contact Information:

E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com

Telephone: (219) 922-7718

Geary Sikich is a Principal with Logical Management Systems, Corp., a consulting and executive education firm with a focus on enterprise risk management and issues analysis; the firm’s web site is www.logicalmanagement.com. Geary is also engaged in the development and financing of private placement offerings in the alternative energy sector (biofuels, etc.), multi-media entertainment and advertising technology and food products. Geary developed LMSCARVERtm the “Active Analysis” framework, which directly links key value drivers to operating processes and activities. LMSCARVERtm provides a framework that enables a progressive approach to business planning, scenario planning, performance assessment and goal setting.

Prior to founding Logical Management Systems, Corp. in 1985 Geary held a number of senior operational management positions in a variety of industry sectors. Geary served as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Army; responsible for the initial concept design and testing of the U.S. Army’s National Training Center and other intelligence related activities. Geary holds a M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance from the University of Texas at El Paso and a B.S. in Criminology from Indiana State University.

Geary is active in Executive Education, where he has developed and delivered courses in enterprise risk management, contingency planning, performance management and analytics. Geary is a frequent speaker on business continuity issues business performance management. He is the author of over 250 published articles and four books, his latest being “Protecting Your Business in Pandemic,” published in June 2008 (available on Amazon.com).

Geary is a frequent speaker on high profile continuity issues, having developed and validated over 2,500 plans and conducted over 275 seminars and workshops worldwide for over 100 clients in energy, chemical, transportation, government, healthcare, technology, manufacturing, heavy industry, utilities, legal & insurance, banking & finance, security services, institutions and management advisory specialty firms. Geary consults on a regular basis with companies worldwide on business-continuity and crisis management issues.