Back in the 1950s and 1960s, Japanese products were synonymous with cheaply made. Anyone over the age of 50 probably remembers cheap Japanese transistor radios when they were a kid. We all believed, in the day, that the more transistors a radio had, the better. That wasn’t necessarily true, but try telling that to a 9-year-old. And of course, we all knew that Japanese radios might claim to have 10 transistors but really only five of them worked.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, Japanese products were synonymous with cheaply made. Anyone over the age of 50 probably remembers cheap Japanese transistor radios when they were a kid. We all believed, in the day, that the more transistors a radio had, the better. That wasn’t necessarily true, but try telling that to a 9-year-old. And of course, we all knew that Japanese radios might claim to have 10 transistors but really only five of them worked.

Conventional wisdom was U.S. made: Good. Japanese made: Bad.

Fast forward 20 years or so, and the same biases, rightfully arrived at, were aimed at Chinese products. As trade relations grew during the 1980s, so did the influx of often poorly made Chinese products. Most people believed that if a product was made in China, it wasn’t going to last. But is that still true today?

Long after Japanese quality was on par or better than U.S. products, the bias that Japanese products were poorly made continued. Ironically, the same situation existed for U.S. automakers when long after U.S. automobile quality caught up and at times surpassed foreign brands, the bias that U.S. cars didn’t have the same quality as their foreign counterparts persisted. Bad impressions linger long after fact.

The question of Chinese product quality is an important one because to understand trade and supplier relationships with China, we need to have a better understanding of where the quality of Chinese products stands and what kind of work is being done, if any, to improve that quality.

Quality in high-tech products

It would be nice if there was a report titled “International Product Quality by Country by Industry by Year: 1980 to 2018.” There apparently isn’t, but we aren’t completely without data.

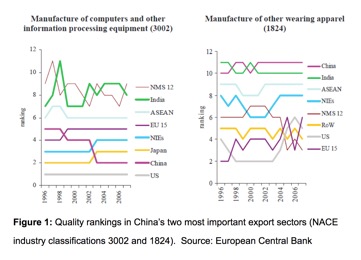

There have been some in-depth analyzes that try to tease out a broad view of Chinese product quality (see References). The most comprehensive we have seen that deals specifically with China comes from the European Central Bank report, “Is China Climbing Up the Quality Ladder?” written in 2011.

This paper challenges the idea that just because a product costs less, it is of less quality. Instead, the ECB report uses not only price, but also information on market share to derive quality. The premise is that quality can be derived from consumers’ preferences, and cheap only goes so far. If the quality of a product is too low, it simply won’t gain market traction.

The most interesting discovery in this report can be seen in the following graphic.

In terms of the quality of computing and related products, China is giving Japan and the United States a run for their money, being second only to the United States, according to the report. However, when we look at wearing apparel, we see that as of 2011, Chinese quality hadn’t changed much. It should be noted that since this report came out, even the garment industry has improved significantly. This information aligns with interviews we have done with several consultants who help connect foreign companies with Chinese suppliers. All agree that the quality of high-tech products, and to a lesser extent garments, has gone up, but not so much in many other products.

One of the conclusions the ECB report arrives at is that “China not only exports the same kind of products as developed economies, but also the quality of these products is similar to the technologically most advanced competitors. In addition, China has increased the quality of its export products and thus poses a potential threat to the market position of the US, Japan or the EU economies.”

In an odd turn of events, domestic manufacturers used to fear Chinese products because they were so cheaply made cost-conscious consumers flocked to them, depriving sales to domestic brands. Now we fear certain Chinese products because they are so well made that consumers may begin choosing them over domestic or European products.

Product safety recalls

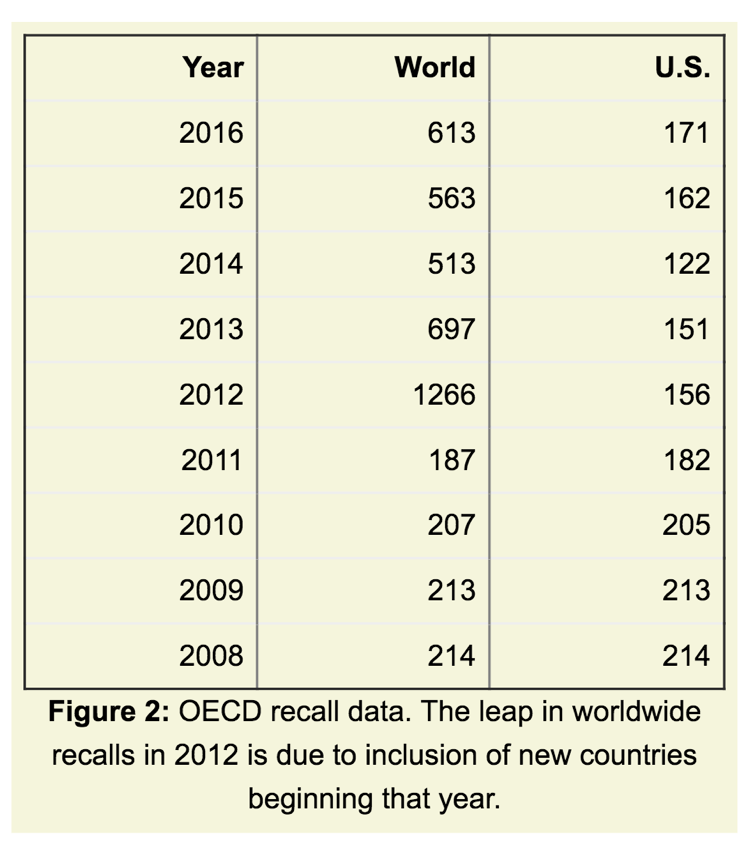

Another data point that gives some insight into Chinese quality is year-over-year product recalls. Both the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) collect these data. The OECD database shows that the number of Chinese product recalls in the United States didn’t change much in the nine years we looked at (see figure 2).

Most of the product recalls are clothes, toys, and home electrical devices (e.g., electric grills, coffee makers). What is largely missing from the product recall list is high-tech products. When it comes to electronics, most recalls dealt with batteries and charging devices. Keep in mind, however, that product recalls are safety related. The lack of product recalls in high-tech doesn’t necessarily mean there are no problems with Chinese tech products, only that any problems that do exist may not pose safety concerns… exploding batteries aside.

The table does reflect a downward trend in recalls from 2008 to 2015, but without knowing other information, such as how many different product names (e.g., SimplyFun Ribbit Board Games) were imported in those years, we don’t have enough information to draw a strong conclusion. However, it is interesting to note that 2008 was the year of China’s deadly tainted-milk scandal; 2011 saw the bullet train crash and its attempted cover-up. The Chinese populace and the world were furious and, according to some, the government began to put more focus on product safety during that same period.

Quality factors

Many factors contribute to whether a country tends to produce quality products or not. Aside from technical expertise, the biggest factor is simply culture. Not big “C” culture as in the entire history and makeup of a country’s ethos, but the short-term cultural identity driven by governance and, to a large part, prosperity. In China’s case, we’re talking about the effect of Mao Zedong and the ugly aftermath of the Cultural Revolution.

Discounting what quality means from a purely technical perspective, quality is often a matter of perception, which is influenced by culture. If you grew up in a poor economy, never having the toys or gadgets that others in developed countries had, your expectation of what quality means could be quite different. And if you haven’t been exposed to the same societal quality and safety concerns that those in developed countries worry about, you may not fully understand how important those concerns are.

‘Children should just be happy to have good, cheap toys. We had nothing growing up.’

Stanley Chao, author of Selling to China (iUniverse, 2012), gives an example of the cultural influence on quality for those raised in the days of Mao. “Most [factory owners or managers] grew up in a time of poverty and hunger, and didn’t even have toys as children,” Chao wrote in Quality Digest in 2008. “Now as adults they don’t understand the big deal about lead paint. As one manager commented, ‘Children should just be happy to have good, cheap toys. We had nothing growing up.’”

Most of us cringe at those words, but as Chao points out, without understanding that lead can kill people—remember that the United States didn’t ban lead paint until 1978—the idea of complaining about the paint on a child’s cheap toy might seem crazy, so why worry about it.

Another example comes from Paul Midler’s book, Poorly Made in China (Wiley, second edition, 2010), in which Midler points out a similar mindset a Chinese contract manufacturer, King Chemical, had when confronted with problems in the pump mechanism for a hand-soap product it was making for a U.S. company.

“King Chemical had workers who were unfamiliar with liquid soap,” writes Midler. “The kind that we [the contracting company] made was a dollar store item, one that you would find in discount stores across the United States. Even if it was a low-end product, consumers expected it to function properly. Chinese workers, who saw such a thing as nearly a luxury, could not see the big deal with a faulty pump. When pumps began to fail, they were inclined to think: So what? You can still unscrew the cap and get to the soap that way.”

Coupled with this, Midler points out how uncomfortable many Chinese are with waste. You don’t throw something away if it can be used, a carryover from poorer times and an idea that is firmly ingrained in the minds of older Chinese. So even if a problem is found, you don’t scrap a bad lot, because that would be wasteful… like throwing away money. Instead, you continue to use it until you run out, says Midler. And that may mean deliberately and surreptitiously selling to the contracting company product you know is defective, or selling it out the back door on the black market.

There is no doubt the Chinese can produce high quality goods. Quality has greatly improved, pretty much in every industry, says Dan Harris, an authority on legal matters related to doing business in China. “Yet we still constantly see Chinese companies send out subpar goods, either because they are not capable of meeting their buyers’ quality standards, or because they simply choose not to even try to meet those standards because they believe they can make more money that way.” And even though one can buy more quality products in China than six years ago “there is also no doubt that there are still plenty of Chinese companies that are happy to cut corners when it comes to quality.”

Middle class a quality driver

If the remnants of poverty and the Cultural Revolution were a driver for China’s poor product quality, its sudden prosperity has been a driver for improving quality. China is seeing an explosive growth of its middle class and, along with that, middle-class values, which include a desire for better, safer products.

According to research by consulting firm McKinsey and Co., only 4 percent of urban Chinese households were considered middle class in 2000. In 2012 it was 68 percent. In 2012, the upper-middle class accounted for 14 percent of urban households, but will make up an estimated 54 percent of urban households and 56 percent of urban private consumption by 2022.

China’s middle class is willing to pay a premium for quality

The authors write that “The evolution of the middle class means that sophisticated and seasoned shoppers—those able and willing to pay a premium for quality and to consider discretionary goods and not just basic necessities—will soon emerge as the dominant force.”

More Chinese citizens will have money to spend on nonessentials. To be sure, many will still buy inexpensive, cheaply made products from China and abroad. But a large segment will expect quality from products originating in their own country. Another McKinsey report, “The Modernization of the Chinese Consumer,” points out that 50 percent of Chinese consumers are increasingly spending on better and more expensive products. For premium products, these are still largely foreign brands, with some exceptions. However, local mass-produced products are gaining market share because they have upped the value proposition. Chinese consumers are no different than any group of consumers: Give us a locally made product with the right quality and price point, and we will gravitate toward the local product.

As an example, reporter Wade Shepard writes in Forbes’ “How ‘Made in China’ Became Cool” that in 2011, 70 percent of smartphone sales in China were from three foreign brands: Nokia, Samsung, and Apple. At that time, “Any self-respecting Chinese consumer wouldn’t be seen dead with a local brand,” says Mark Tanner, director of China Skinny, a Shanghai-based consumer research firm.

But now, 8 out of 10 smartphone brands are Chinese, with Huawei, Oppo, and Xiaomi leading the pack. And not just in China. Worldwide, Huawei and Oppo are directly on the heels of Samsung and Apple, with other Chinese brands right behind them. Not because they’re cheap: A top-of-the-line Huawei P20 Pro will set you back $2,600.

“We’ve seen established foreign brands with historically high consumer regard, such as Nike, Apple, and IBM, give way in popularity to local Chinese brands that have stepped up, like Li-Ning, Huawei, and Lenovo,” says John Niggl, a client manager at InTouch Manufacturing Services, an U.S.-owned company that provides inspection and related quality control services solutions to overseas manufacturers. Whereas 10 to 20 years ago there was a perception among many Chinese consumers that foreign brands offered higher quality, there’s a growing perception, says Niggl, that domestic brands offer the same or better quality without the high import taxes that accompany American products.

According to a Bain and Co. report, in 2017 nearly one-third of the money spent around the world on luxury items (e.g., high-end bags, shoes, watches) came from Chinese nationals. And of course Chinese manufacturers want to cash in on that market as much as any manufacturer. To do that they will have to improve the quality of those products. They have the expertise and the technology. Now with local consumers demanding better products, they have the driver.

“As a whole, Chinese manufacturers don’t have the same level of craftsmanship as the Japanese,” Tanner tells us. “However, there are a significant number of ambitious, well-resourced manufacturers with cutting edge technology and a vested interest in high quality outputs in China who are manufacturing to a standard at least as good as the West. These brands are not only higher quality than ever before, but they are more nimble than businesses I have seen anywhere else in the world—they have to be to survive in China.”

“Made in China” no longer necessarily means cheap or knock-off, though that still exists. China has the expertise, the engineers, and the infrastructure to make quality products, and is doing so. It also has the necessary drivers: a growing middle class with buying power, and the desire to improve the “made in China” brand and compete head-to-head in the global market. In part two we will take a look at what is being done to improve quality, and how foreign manufacturers contracting work to China can help ensure that their product is properly made.

(C) Copyright – Quality Digest – Used with Permission

BIO:

Dirk Dusharme @ Quality Digest

Dirk Dusharme is Quality Digest’s editor in chief.

References

Claudia D’Arpizio, Caludia, and Federica Levato, Marc-André Kamel, and Joëlle de Montgolfier, “Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study, Fall—Winter 2017,” Bain & Co., 2017.

Pula, Gabor, and Daniel Santabárbara, “Is China Climbing Up the Quality Ladder?” European Central Bank, 2011.

Jie Xiong and Sajda Qureshi, “The Quality Measurement of China High-Technology Exports,” Elsevier, 2013.

Houseman, Susan, and Christopher Kurz, Paul Lengermann, and Benjamin Mandel, “Offshoring Bias in U.S. Manufacturing,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2011.

Andersson, Emelie, and School of Social Sciences, Södertörn University, “Attitudes Towards Products ‘Made in China,’” Södertörn University, 2015.

Hallak, Jaun Carlos, and Peter K. Schott, “Estimating Cross-Country Differences in Product Quality,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2008.