There are many risks involved in creating high quality software on time and within budget. With ever-increasing software complexity, increasing demands for bigger and better products, and even decreasing time to market, the software industry is a high-risk business.

There are many risks involved in creating high quality software on time and within budget. With ever-increasing software complexity, increasing demands for bigger and better products, and even decreasing time to market, the software industry is a high-risk business.

When software teams don’t manage these risks, they leave their projects vulnerable to factors that can cause major rework, major cost or schedule over-runs, delivered product that don’t match their intended use requirements (for example, product that have safety, security, usability or functionality gap) or other project failures.

RISK OF NOT MANAGING SOFTWARE RISK

RISK OF NOT MANAGING SOFTWARE RISK

In software development, the possibility of reward is high, but so is the potential for disaster. Risks exist whether they are acknowledged or not. People can stick their heads in the sand and ignore the risks but this can lead to “unpleasant surprises” when some of those risks turn into actual problems.

The need for software risk management is illustrated in Gilb’s risk principle. “If you don’t actively attack the risks, they will actively attack you” [Gilb-88]. In order to successfully manage a software project and reap the rewards, software practitioners must learn to identify, analyze, plan for, track and control these risks.

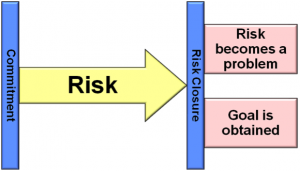

That said, what do we mean when we are talking about a “risk”? A risk is simply the possibility of a problem occurring sometime in the future. I f it is already a problem, put it on the problem list and deal with it — it is not a risk. If it has a 100% chance of happening, it is already a problem – a risk has some possibility of not turning into a problem.

START AND END OF RISK

A risk starts when a commitment is made. For example, every time I cross the street, I run the risk of being hit by a car. The risk does not start until I make the commitment, until I step in the street. We don’t have the risks of ACME delivering a low reliability software component or of ACME being late in delivering that software component until we make a commitment and select ACME as the subcontractor for that component. If we choose instead to build the software component in-house, a different set of risks exist. We don’t have the risk of a requirement not being feasible until we commit to include that requirement in our product.

A risk ends when one of two things happen:

- Bang!! We get hit by the car in the middle of the street. The problem actually occurs. It is now a problem and is no longer a risk. Other examples where the risk turns into a problem and stops being a risk include:

Figure 1 – A Risk is the Possibility of a ProblemACME delivering a low reliability subcontracted software component

- ACME being late in delivering the subcontracted software component

- We cannot figure out how to design and implement the committed to requirement

- Or we safely step onto the sidewalk of the other side of the street. The risk disappears because there is no longer the possibility of a future problem. Our goal has been obtained. Other examples where obtaining the goal removes the risk include:

- ACME delivering the subcontracted software component on time with the required reliability

- We are able find an effective way to design and implement the committed to requirement

Before it turns into an actual problem, “a risk is just an abstraction. It’s something that may affect your project, but it also may not. There is a possibility that ignoring it will not come back to bite you.” [DeMarco-03] If we ignore the risk and run into the street without looking, there can be dire consequences. Not every time — in fact we can get away with it over and over again. But then it only takes once.

In this series of short papers, I will discuss the practices, principles and tools of risk managements and how to apply risk management to various aspects of software development.

Bio:

Linda Westfall is the president of Westfall Team, Inc. which provides software engineering, quality, and project management training and consulting services. She has more than 35 years of experience in real time software engineering, quality, project management and metrics.

Linda is the author of The Certified Software Quality Engineer Handbook from ASQ Quality Press. She is a past chair of the ASQ Software Division and has served as the Division’s Program Chair, Certification Chair and Marketing Chair, and on the ASQ National Certification Board. Linda is an ASQ Fellow and has a PE in Software Engineering from the state of Texas. Linda is also a Grand Master of the Pyrotechnic Guild International.