I was coaching one of the national oil companies in the Middle East, offering mentorship to the director of their operational excellence program. He was frustrated because he had invested considerable funds building a team of sixty Lean Six Sigma Black Belts over a nine-month period, and they had not yet worked on—much less completed—any project nor had they realized any benefit to the company.

Even worse, while these newly-minted Black Belts were sitting idle without the opportunity to use their new-found skillsets, some became frustrated themselves and left the company—taking the company’s investment with them.

Never mind the fact that a person should not be considered a Black Belt without completing at least one project and leading a few others—demonstrating their comprehension of the materials learned and command of applying these skills—I was left wondering why the company was investing in the training at all. In essence, the company was building inventory for which they had no requirement. One of the primary rules of Lean is to not build inventory unless its needed, shouldn’t this rule also apply to investing in building skillsets in people?

My coaching advice was twofold: Get the existing resources working on projects, and don’t invest in building any more resources unless you have projects for them to immediately work on. Ideally, they should work on these projects during training. I also suggested that there might be a disconnect with in his organization, because it seemed those who would have a demand for the resources actually did not (or perhaps they did not actually buy into the program), even as the considerable supply of capable resources was being built. There is danger in “having a logistic in search of a strategy.”

So, what’s the best way to build capacity and capability in your organization?

The first step it to make sure;

- your organization has a need for the skills in which you are about to invest and,

- has the desire to utilize the newly skilled resources once created and,

- the importance of these efforts is a strategic priority to the organization achieving its vision.

If all three of the above conditions are not met, stop. Re-assess the situation. You are proposing to invest in something that the company does not want badly enough—and only doom awaits.

Assuming all three of these conditions are met, what is the best way to design and deploy an education and training program that is efficient (highest value for lowest cost) and effective (benefits are near-term, and the knowledge transfer has a high retention rate which begets wisdom)?

The biggest challenge in building capacity and capability is avoiding “stall speed.” As they say on WallStreet: “lose a day, lose a week; lose a week, lose a month; lose a month, lose a quarter; lose a quarter, lose a year.”

Traditional methods of training and education is for a cadre of trainees to go to some facility other than their normal place of work to receive the training and education. But there are nearly insurmountable challenges and inefficiencies in this approach which will jeopardize the effectiveness of the outcome and even the very success of the program. Some of the more significant risks are;

- Time; It takes a considerable amount of time to organize and deliver a class. First and foremost, is the challenge of coordinating the schedules of the trainees so that they can attend. The training and education compete with other activities and events both internal to the organization and personal to the trainees. You might be able to identify a cadre of trainees, but their combined first availability might be three months (or more) away.

- Work/Trainee balance; Related to time and scheduling is the conflict between the trainee fulfilling the primary responsibilities of their job to the company and being trained. When push comes to shove, the trainee performing their primary responsibilities will come first over training. This means the trainee will often be forced to forego the scheduled training in favor or work.

- Expense; Travel costs will add significantly to the investment requirements necessary to deliver the training and education.

- Scalability; It is much more difficult to scale a program and have multiple cadres of trainees being trained simultaneously. The reality will mostly likely be that only one cadre (of no more than 25 trainees) is being trained at any given time. Considering that a course might run 13 to 26 weeks, this means that no more than 100 trainees will go through the program per year.

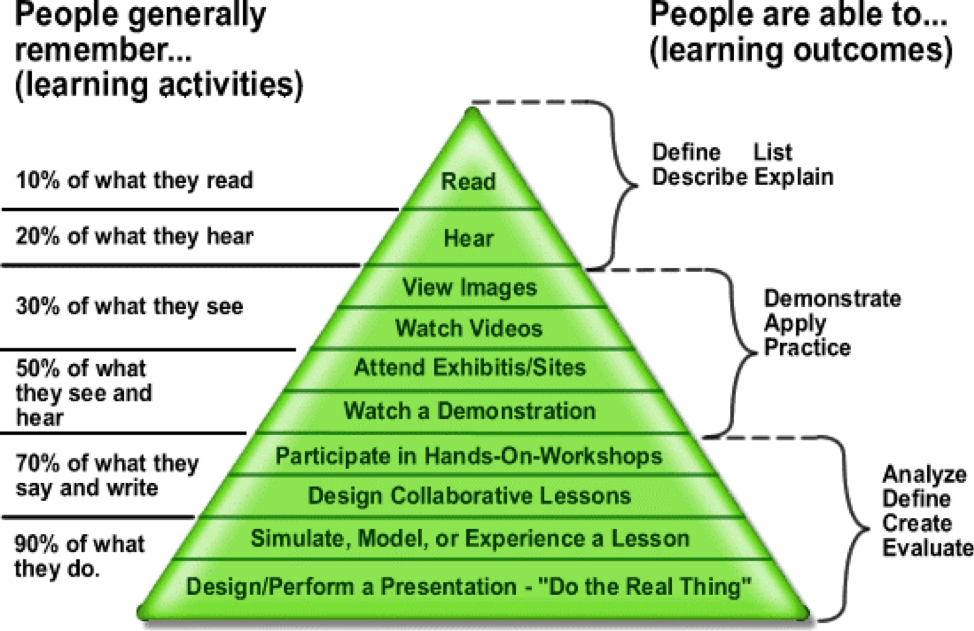

- Retention rate; According to the Edgar Dale “Cone of Experience”, the more experiential the learning, the greater the retention by the trainee of what they are learning. Of course, there are those who, disagree with the “percentages” and others who break the task of learning in more granular detail, but the general premise is; the more knowledge you are exposed to and the greater the experiential component, the greater the retention – with the greatest level of retention being obtained when the trainee is able to apply what they have learned.

- Atrophy; As they say; “if you don’t use it, you lose it.” Knowledge learned has a “half-life”, in that what a person learns and retains is reduced by half, and half again and again, if not put to use. Studies vary, and it is also dependent upon the complexity of the subject being learned, but this half-life can be measured in as little time as a few days. Similar to retention rate, the best is to put new knowledge to work as immediately as possible – preferably in scenarios which are specific to the trainee.

The Basics of Integrated Learning

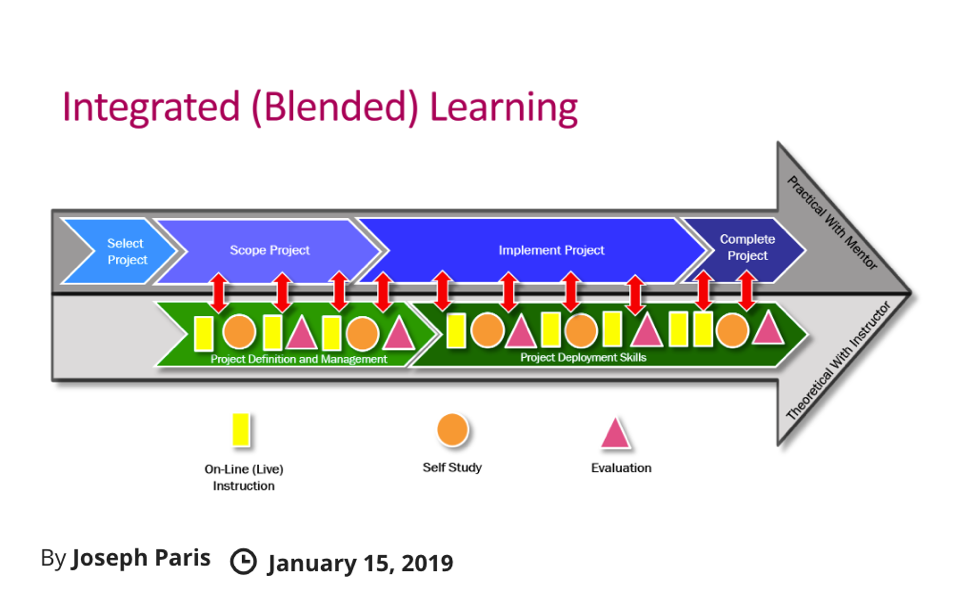

Integrated learning (sometimes called blended, hybrid, or mixed-mode learning) is a method of learning where the trainees study a subject using materials and resources that are both on-line and off-line (videos, text books, and other instructional materials). The trainee’s journey through the “theoretical” component of the coursework is facilitated live and in-person by a subject matter expert who leverages telephony. There is also a “lab” or “practical” component to the learning, with the trainee working on a project that exercises the skills they are learning in the theoretical component.

To visualize the experience, think of a “virtual university”.

Trainee selection

As they say, “quality over quantity”. It is wrong to set, as a metric of your program, some number of trainees being trained. Better is to set a metric for the number of qualified trainees being trained. Here, qualified means the selection of trainees who; i) have the disposition to learn what they are being taught, ii) the time available to successfully complete the program, and iii) become a force-multiplier to the organization when the training is completed.

This means the organization will require a candidate nomination and screening process – with clearly defined success criteria – defined up-front. No trainee should be accepted into the program without having passed the screening process.

Must have a project and a mentor

To overcome the risks associated with retention and atrophy as noted above, every trainee must have a project to which they plan to apply the knowledge they are receiving. In addition to a project, the trainee must also have a mentor from within the organization assigned from within the organization and who will be the trainee’s “Sherpa” – responsible for supporting the trainee in the practical application of the theory they are learning in their project. Both the project and the mentor must be approved by the organization and should be a component of the screening process.

Classes of approximately twenty-five individuals

Classes should be large enough to maintain energy and inspire collaboration among the trainees while being cost effective. Given the coaching and mentoring resources required, my experience has been that a class size of approximately twenty-five trainees is optimal (similar to standards found in education). If the class size is much smaller, the amortization of the delivery costs becomes a challenge. And if the class size is much larger, management of the trainees by the instructors, coaches, and mentors becomes unwieldy and less efficient.

As the program grows and additional teaching resources become available, it might make sense to scale the program to accelerate its impact and amplify the results realized. This can be accomplished by delivering multiple classes simultaneously, so long as each class has no more than twenty-five students.

Two tracks for learning; theoretical and practical

Building the theory: Online and offline lectures and materials

The instructors may or may not be a resource from within the company; they are subject matter experts and teachers. It is optimal to deliver as much of the theoretical as is appropriate, by leveraging telephony wherever possible. This will accelerate the delivery of the content while minimizing the costs associated with travel. Here, the instructor will deliver live lectures via the Internet and in a structured manner similar to a university course.

Depending on the technology used for delivery, the trainees should be able to see the instructor and the content being presented, as well as the other trainees during interactive sessions. In essence, the delivery system should approximate a cyber-classroom. In the case where a trainee might miss alive lecture, it might also be possible to record the lectures and archive them for later reference—perhaps even share them with similar classes within the company, which could reduce future instruction costs.

In addition to the live lectures, the trainees will be given offline reading assignments and exercises from books, videos, online content, or other sources as structured within the curriculum. This offline content is organized and integrated into the overall class in a meaningful manner and woven throughout the course.

The trainee will also engage in assessments at key waypoints in the curriculum to ensure satisfactory progress and to identify areas of weakness, either in the trainee’s abilities or in the curriculum itself.

Building the practical: Applying the theory on a project

As mentioned above, the trainee must not be assigned a class or start the curriculum without first having an approved project to work upon for the practical component of their learning and a mentor assigned to support the trainee journey. The purpose of this is twofold: First, the trainee gets to apply the theory they are learning, thereby increasing the retention rate of the knowledge, and, second, the approach will yield a net benefit to the company because a project will be completed at the conclusion of the course.

The financial benefit to the company from having completed a project should more than offset the hard and soft investment required to train the trainee. Accordingly, if this approach is properly followed, the program will not only have no cost burdens on the company but should also immediately return a net financial benefit (as well as future benefit from subsequent projects completed).

Building organizational capability and capacity for free

It’s a challenge – getting the support for any initiative within an organization. It’s even more of a challenge when there only appears to be a need with few (or no) tangible benefits – only hypotheticals.

Leveraging integrated learning to enhance the skillsets of your employees and build capability and capacity across your organization in the manner prescribed above will result in tangible benefits which will more than offset any hard and soft costs associated with such a program – making the program itself both credible and sustainable.

And, aspart of a properly architected overarching employee development program, produce high-performing individuals as the critical and necessary building blocks for becoming a high-performance organization.

by Joseph Paris

Paris is the Founder and Chairman of the XONITEK Group of Companies; an international management consultancy firm specializing in all disciplines related to Operational Excellence, the continuous and deliberate improvement of company performance AND the circumstances of those who work there – to pursue “Operational Excellence by Design” and not by coincidence.

He is also the Founder of the Operational Excellence Society, with hundreds of members and several Chapters located around the world, as well as the Owner of the Operational Excellence Group on Linked-In, with over 60,000 members. Connect with him on LinkedIn or find out more about him.