Organizations need controls to ensure objectives are achieved. Management’s job is to establish, implement and monitor controls, and the auditor’s job is to determine whether they are adequate.

Organizations need controls to ensure objectives are achieved. Management’s job is to establish, implement and monitor controls, and the auditor’s job is to determine whether they are adequate.

In some cases, organizations adopt standards that require controls. Many performance standards call for control of an activity, process, function, department or system.

Some people think of a standard as a set of controls to address a particular need, such as to ensure a quality product or service is provided, or that environmental risks are minimized. When auditing against standards that require control, it is imperative for auditors to be able to determine whether control is adequate.

Organizations, therefore, need to be able to demonstrate to auditors that they have implemented adequate controls relative to the importance or risk of the activity.

Wordplay

The word control can be used in titles such as “control of production” or “control of measuring devices.” It also can be used to describe a document such as a “control plan.”

When control is used as a verb, there must be some type of action that achieves a goal or objective. For example, “The organization shall control the distribution of customer intellectual property.”

When control is used as a noun, it implies all necessary means should be used to ensure objectives are achieved. For example, “Organizations must implement controls or management must ensure the control of product labeling.”

When control is an adjective, it describes a noun such as a control chart or control plan. This indicates the plan contains parameters for a process, product or service.

Regardless of how the word is used, it’s meaningless if that’s all it is—just a word. For example, the Code of Federal Regulations Title 21 says, “Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures to control labeling activities.”1 But just because an organization has established a labeling control procedure doesn’t mean it has met the requirement to control labeling.

A procedure is one tool a manager has to ensure processes are controlled. In some cases, however, procedures are worthless except to meet a requirement.

During an audit I conducted, I asked a truck driver how he loaded the truck. He responded, “Do you want me to tell you what’s in the procedure or what we actually do?”

Management uses many tools to ensure operations are controlled. Control tools can include procedures, checklists, schedules, reviews, policies, budgets, instructions, forecasts, pro forma statements, reports, flowcharts, video surveillance, statistical techniques, training, records, software, devices and internal auditing.

With such a host of tools available, how does management decide which combination of tools is needed? How much is enough? When is it too much? For example, do you need a security officer outside the break room logging people in and out?

Control concept

For organizations such as the Institute of Internal Auditors, internal control is a business concept. Businesses need internal control to achieve profitability, meet performance targets and prevent loss of resources. Internal controls are needed to provide reasonable assurance that objectives will be achieved.

While all of that makes sense, I’m not sure that—even as an auditor—I’m any closer to answering a few fundamental questions:

- What is control?

- How do I know it exists?

- How do I determine whether controls are adequate?

We know management implements and maintains controls, while auditors test for the controls. Perhaps auditing is nothing more than verification of required controls.

Some standards have prescriptive “to-do” requirements that must be included in the control of an activity or process. When the control is audited, auditors can check off that certain prescriptive requirements are in place.

For example, for incoming orders that must be controlled:

- There must be a procedure that ensures orders are controlled.

- Orders must be recorded.

- Orders must be reviewed prior to acceptance.

- Order changes must be communicated to all interested parties.

If auditors check off the four requirements, does the organization pass? Is the activity adequately controlled? Are incoming parts still bad? Are materials being returned?

When a standard has a prescribed list of requirements, auditors can check off the areas in which the organization has addressed each requirement. The implication is that if the organization addressed each specified requirement—as with incoming orders—the process is controlled. Adequate control is then linked to the prescribed list of requirements.

Control process

We assume the prescribed list provided by the standard writers is commensurate with the risk and anticipates all situations. But this may be faulty thinking.

What if the requirement is open-ended? For example, it may say that management must control the work environment and ensure it is safe. What if there is no specified requirement list? What if the standard’s requirement is that incoming orders must be controlled to ensure customer requirements are met?

It is a reasonable requirement to control incoming orders. But the auditor charged with the responsibility to verify compliance doesn’t have a prescriptive list to follow and must ask him or herself a few questions to get to the bottom of the situation:

- What is the basis for noncompliance?

- What evidence would withstand the scrutiny of the exit meeting and a subsequent review if a nonconformity is appealed or questioned?

- When requirements are open-ended, must the auditor be willing to accept any rational scenario, or can the organization be challenged?

Standards may be viewed as a list of activities that must be controlled. Some standards have more prescriptive requirements than others. It is impossible for standard writers to anticipate every situation. Therefore, auditors must have a test to determine whether management is controlling the process or activity as required. This is when the process technique can be helpful to auditors.

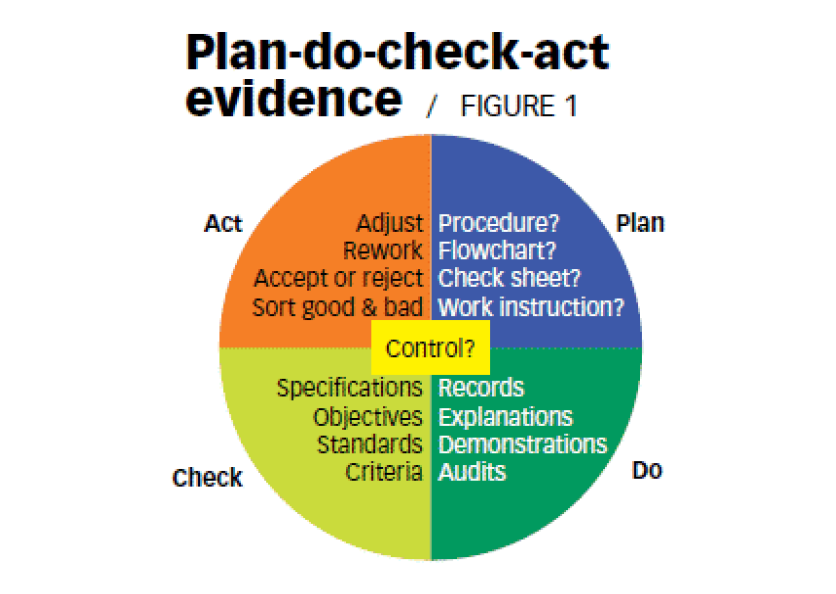

The process technique uses the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle:

- Plan. A plan, procedure or method is developed (establish what needs to be done).

- Do. The plan, procedure or method is being followed (do what was planned).

- Check. The plan, procedure or method is monitored or measured against a criterion (know when it is done right or wrong).

- Act. Action is taken to resolve the differences between expected and planned results (for example, analyze and adjust to the process or activity).

For management to control a process or activity, a predetermined method must be established. Without it, there is no basis to monitor or improve. The predetermined method can be in any form and should be designed based on the process or activity being controlled. The predetermined method must be followed for the monitored or measured data to be useful.

Next, management must determine the criteria or objectives for success or acceptance. If any output of the predetermined method is acceptable, the process does not need to be controlled.

Lastly, management must act on the results of comparing outputs to objectives. If management does not act on the results, either the process does not need to be controlled or management is

incompetent. See Figure 1 for examples of evidence you may need to verify that controls are adequate.

At the basic level, an organization must address the four process technique requirements contained in the PDCA approach for there to be adequate control. With those techniques in mind, we may want to define management control as: “When predetermined plans are followed, monitored against acceptance criteria and adjusted as needed to achieve objectives.”

Control levels

Not all controls are the same. The extent or levels of control must be relative to their risk to the organization. Every organization faces a variety of risks to its survival. The higher the risk, the more formal or complex the controls should be. The controls for a nuclear power plant are different than for a hotel. Organizations should assess the consequences of failure and establish controls relative to those consequences.

Management identifies processes that need to be controlled either from self-determination or based on what is required by law. For control to be adequate, it must be at the appropriate level relative to the organization’s type, size, complexity, risk and competency of employees.

From the highest level, the board of directors and CEO may determine there needs to be control of financial reporting, effectiveness of operations, and compliance to laws and regulations.

Auditors have at least two approaches that can be used to ensure controls are adequate: the PDCA for auditing technique and the requirement techniques referenced in the standard—for example, in ISO 9001:2015, subclause 8.5.1, Control of production and service provision.

The requirement technique has a handy list to consider for controlling an operation or process. Based on that, an auditor can compile a checklist.

Ask yourself

For there to be management control, there must be a predetermined method. This method should be followed and monitored, and there should be a means to adjust the process.

Universal interview questions auditors should ask are:

- How do you know what to do?

- Can you show or tell me how you do it?

- How do you know when it is done right?

- What do you do when it’s not done right?

The answers to these questions should reveal enough information to reach the correct conclusion. Use them to test an organization’s controls, regardless of whether there is a prescriptive list. And, if controls aren’t adequate, report the situation so it can be remedied.

References

1. Food and Drug Administration, “Code of Federal Regulations Title 21,” subpart K, section 820.120, 2010.

About the author

J.P. Russell is an ASQ Fellow and a voting member of the American National Standards Institute/ASQ Z1 committee. He is a member of the U.S. Technical Advisory Group to Technical Committee 176, the body responsible for the ISO 9000 standard series. Russell is the managing director of the internationally accredited Quality Web-Based Training Center for Education, www.qualitywbt.com, an online auditing, standards, metrics, and quality tools training provider. A former RAB and IRCA lead auditor and an ASQ Certified Quality Auditor, Russell is author of several ASQ Quality Press bestselling books, including Process Auditing Techniques; Internal Auditing Basics; ISO Lesson Guide 2015: Pocket Guide to ISO 9001:2015; and he is the editor of the ASQ Auditing Handbook.

Please note: This article first appeared in the ASQ Quality Progress Standards Outlook column June 2011. The article has had minor revisions to ensure its relevance with current perspectives.