Organisations exist in a dynamic world where business uncertainty and socio-political volatility can adversely affect their existence. The mass of data available and the contradictory interpretations that can be made add ambiguity and complexity to the mix. Our modern day organisations, or at least their management or leadership team realise, or should realise, that their operating environments are changing and, in order to adapt and survive, they too need to change.

Organisations exist in a dynamic world where business uncertainty and socio-political volatility can adversely affect their existence. The mass of data available and the contradictory interpretations that can be made add ambiguity and complexity to the mix. Our modern day organisations, or at least their management or leadership team realise, or should realise, that their operating environments are changing and, in order to adapt and survive, they too need to change.

About 2,500 years ago the Greek Heraclitus philosophised that “the only constant in life is change” and he wasn’t wrong; and it’s not just that people live and then die. Empires have come and gone, countries emerge and disappear, and organisations succeed, or fail, or merge or are acquired. In order to survive we all need to adapt to the external environment whatever it may bring. But people don’t generally accept change and many will hanker for the past and ‘the good times’. “Living in the Past”, as the band Jethro Tull reminded us, may be about happy and smiling because our selective memories conveniently forget the bad times and embellish the good.

Corporations are no different and, as only the fit survive, change becomes the exercise required to stay fit. There are tomes written about corporate change, how to implement it and why it’s resisted. But what happens when change is required and planned but the very people who desire change want to live in their rose-tinted past?

Resisting Change

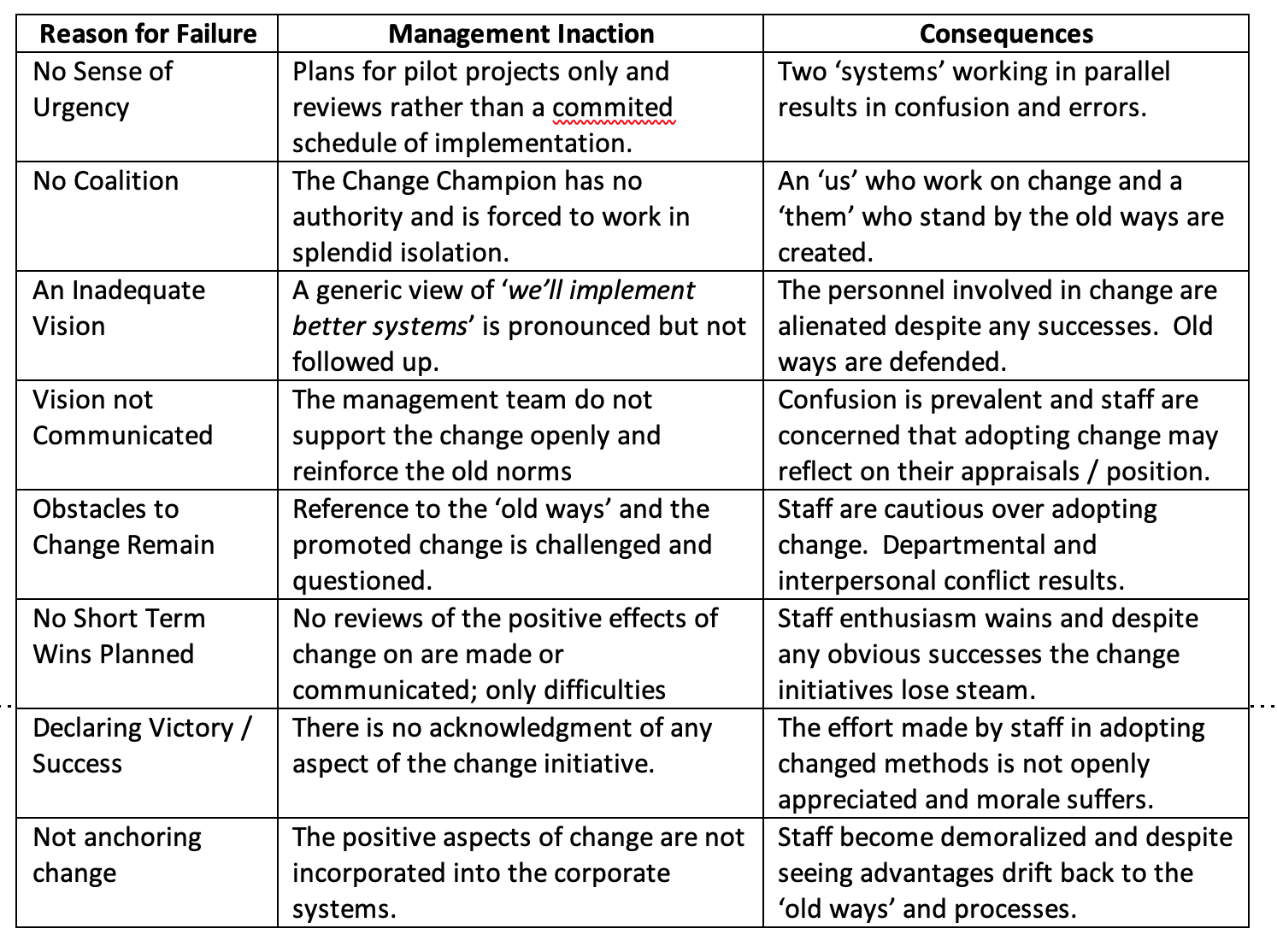

The management guru Kotter cited eight reasons for resisting change and, while the lack of management support to a change initiative is identified as the root of failure to change the consequences of such management failure can be dire. The reasons and the immediate consequences of management’s inaction and clinging to a perceived ‘glorious past’ are summarised below:

An organisation, or rather its management team or leadership body may realise today that they need change. However, in the inertia of adapting to change an ineffective leadership will dwell on their selective memory of the past and possibly conclude that things weren’t so bad after all and the organisation worked. There’s also the fear at the leadership level that the systems they believed in and possibly even created are no longer effective and they may be criticised for not getting it right in the first place.

Failed Change

If change doesn’t go well and there are hiccups along the way it is all too easy to blame the ‘new’ and defend the ‘old’. The manager who felt threatened by change and whose ego was challenged may well use these hiccups as a way of poo-pooing change. The old, and ineffective way of working is heralded as being effective anyway and becomes even more ingrained into the corporate psyche and culture. The move for ‘change’ loses momentum at the first hurdle and the hubris of the old guard is reinforced while those who support change are downtrodden.

The change initiative now becomes a survival plan as it competes against resistance reinforced by general reluctance. The once threatened management team may now feel vindicated that the old way was OK but, in a self-satisficing gesture let the change plan progress in a ‘let’s try it and see’ act of benevolence with no intention of acceptance. Such egotistical actions place the change process under such close scrutiny that every error is exaggerated and the overarching aim to change is clouded by criticism.

Failing to Change

Unfortunately, the original requirement for change is forgotten in the midst of criticism, accusations of failure and failed attempts. The resulting turf war between the advocates for change and an old guard who defend the established ways and their established position of power detracts from progress. Such arrogance and dogma may derail the change process but in the long run it may well accelerate the demise of the organisation.

Corporate Executives need to realise that there is a problem and be above the personalization of issues and accusations that individuals are wrong or not capable. Mistakes are made and, like most mistakes, they can be corrected; but in any event they should not be held onto just because a long time was spent making the mistake. If pride and ego get in the way the mistake is compounded and failure is inevitable. For a change program to work it requires inward reflection and the modest acceptance that change must happen rather than a hubristic belief that all is well there’s no room for improvement.

Conclusion

Unsuccessful change is not good. This can galvanise the belief that there is nothing wrong and any ’change’ is then believed to be wrong and merely reinforces the old way.

If the ‘old way’ allowed for a lack of rigorous process and planning then management based upon whims or fancies will prevail. If the old way required mandatory and inflexible approaches then any agility to adapt to situations will be stultified.

For an implemented change program to succeed prior preparation and planning coupled with a positive commitment are essential for success. An underlying belief that everything is tickety-boo and hunky-dory will reinforce the status quo and change will fail; arrogance and futility will prevail.

Bio:

Malcolm Peart is an UK Chartered Engineer & Chartered Geologist with over thirty-five years’ international experience in multicultural environments on large multidisciplinary infrastructure projects including rail, metro, hydro, airports, tunnels, roads and bridges. Skills include project management, contract administration & procurement, and design & construction management skills as Client, Consultant, and Contractor.