How to get better results by solving problems before they occur in a fragile world

How to get better results by solving problems before they occur in a fragile world

When people think of problem-solving, their mind may instinctively jump to thoughts of things that are broken or things that need fixing.

Problem to most people is a matter or situation regarded as unwelcome or harmful and needing to be dealt with and overcome.

Problem-solving skills help us determine why a thing is broken or a problem that has occurred and how to resolve that problem. It starts with identifying the problem, coming up with options and solutions, implementing the best solutions to overcome the problem and evaluating the effectiveness of the solutions implemented.

Paying a premium for high-quality problem solvers

Consultants (and executives) are paid big bucks to solve problems.

Interestingly, consultants don’t get paid to predict their clients’ weather; they just need to offer umbrellas to people who seem to always need and buying them. They usually make tonnes of money by charging their clients based on value.

Organisations pay consultants to reduce their runaway cost, etc. and take them back to their previous cost levels. Everyone is happy. Things go back to the status quo. Nothing is made better, unfortunately.

In workplaces, jobs that place high importance on “making decisions and solving problems” pay much more. Positions that involve more problem solving, like physician assistants and chief executives, rank higher in terms of pay. Jobs that don’t require much problem-solving, like a tour guide and a waiter, rank lower.

Many CEOs are also paid handsomely for turning around ailing or loss-making businesses. They are not paid for preventing problems. These CEOs are remunerated for fixing a broken thing.

Rather than experiencing the negative impacts of a problem and trying desperately to fix the problem with large sums of money, why not predict and pre-empt the occurrence of the problem before it converts into a real problem? It will cost less and have lower consequences.

Isn’t it better to predict and pre-empt a problem beforehand before it converts into a costly problem?

You would think so. It does make economic and logical sense. But it usually does not happen in practice.

Changing the way we think about problem-solving

We tend to celebrate and reward people who solve existing problems. It is not normal to find someone who can effectively predict the likely occurrence of a potential problem, a known uncertainty, or a risk (a ‘baby’ problem).

Going through the pain of solving a problem rather than predicting a problem is something we ‘enjoy’ doing. We tend to pay large sums of money for that privilege.

There is no glamour in identifying an uncertain event before it converts into an actual problem, unfortunately. No tangible achievements are associated with it.

It takes a crisis to get things done

People will usually focus on fixing things that are hurting them right now. They prefer to solve a real tangible problem or eliminate an existing pain as an achievement under their belt.

Here’s a trivia question for you: Did you have a fully tested up-to-date business continuity or pandemic plan in place before December 2019?

Business continuity professionals will tell you that their clients and employers do not place much value in planning for future, planning for potential business disruptions, or even planning for a pandemic that may never eventuate.

Getting executives to attend business impact workshops, and writing up and maintaining business continuity and even pandemic plans have been a significant challenge pre-COVID-19.

Many pay lip service to being prepared for emergencies. The majority were never prepared for the impact of a pandemic.

Then came the pandemic in early 2020. People were frantically dusting off their business continuity plans (if they had one). They started to review them. But many were caught with their pants down without any plans in hand!

Business continuity planning suddenly became the top agenda item at the board and executive meetings. But it was too late for many.

As I have always said, it will always take a costly crisis for executives to take things seriously!

We have seen businesses paying huge amounts of money to consultants to develop their pandemic responses when COVID-19 was unfolding in front of their eyes.

Many governments were also not prepared for the pandemic, as shown in some of the news headlines below.

A few places, such as Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong, took early steps of containment and mitigation, having institutionalised lessons learned from the 2003 SARS epidemic.

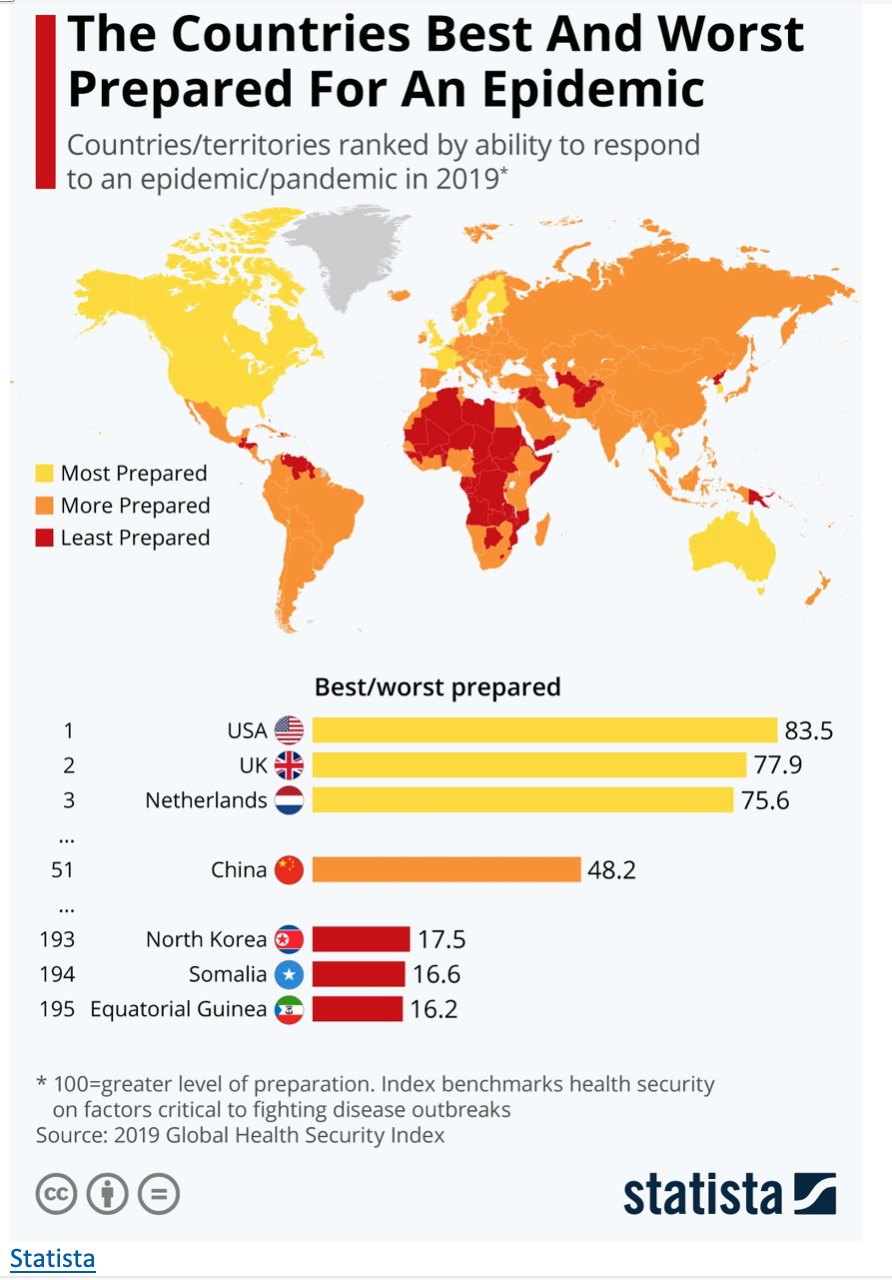

While the USA was ranked the “most prepared” in terms of its ability to respond to a pandemic in 2019 (shown below), it wasn’t the case in 2020! What a stark contrast between reality and perception.

America’s ongoing struggles with the coronavirus have caused tremendous human and economic pain. The pandemic has exposed deep political divisions and a disinformation ecosystem that muddies even the hardest facts.

America’s ongoing struggles with the coronavirus have caused tremendous human and economic pain. The pandemic has exposed deep political divisions and a disinformation ecosystem that muddies even the hardest facts.

Despite more than 188,000 deaths (and growing daily!), the U.S. remains fatally divided over how to deal with a pandemic that will surely last for months more, if not longer.

As bad as these last several months have been, it will be foolish to assume that COVID-19 is the worst the future could throw at us.

It is easier to blame others than to take responsibility for inaction

Many commentators labelled the COVID-19 pandemic crisis as a ‘Black Swan’ event. But the reality is that COVID-19 was not a black swan, as shown below.

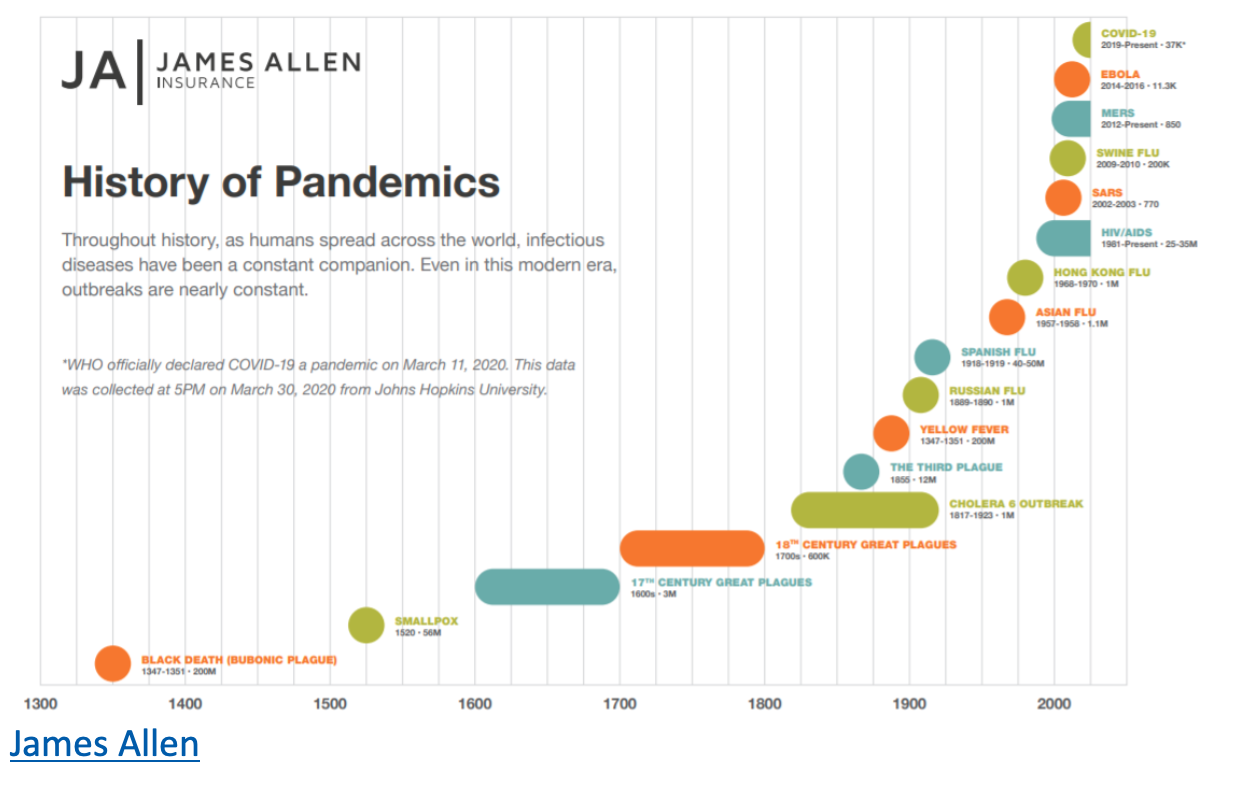

Looking back at history, we have experienced so many other pandemics in the past that it was only foreseeable that a pandemic was coming, as shown in the diagram below. It was only a question of when not if.

In the Bible, we read that Adam sinned by disobeying God’s command “but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” (Genesis 2:17).

Instead of taking responsibility for his inaction by not preventing Eve from eating the fruit from that forbidden tree, Adam blamed God. He said, ‘The woman you put here with me — she gave me some fruit from the tree, and I ate it.” (Genesis 3:12)

We tend to find excuses or blame other people for our inactions or inadequacies rather than taking responsibility for our actions and decisions.

The good thing that has come out of the pandemic crisis is that governments and organisations have taken business continuity and pandemic planning seriously.

We saw how fast organisations got their technology in place for working from home. Things that took months to do, took only days to fix!

Over time, no doubt, memories will fade. Pandemic plans will get shelved and ultimately forgotten until the next major pandemic arrives. Complacency will set it, as always. Business continuity as an agenda item at executive meetings will ultimately vanish. And the cycle will begin all over again.

Proactive management vs. reactive management

We would rather get a kick in the backside and reacting to an existing problem than proactively preventing a problem from occurring or preparing for it. Organisations and governments would rather experience the consequences and pay big bucks to fix a broken thing than to prevent problems from occurring in the first place.

People would rather be complacent and do nothing than to take pre-emptive action on an uncertain event that may likely occur in the future based on emerging trends and signs.

Organisations and governments would rather practice reactive management than proactive management.

- Proactive management is thinking ahead, anticipating and planning for a potential problem, change or crisis.

- Reactive management is reacting to problems or crisis after they have occurred. By definition, reactive management is characterised by the lack of planning or complacency.

As the saying goes, we don’t plan to fail but we fail to plan.

Executives would wait for the occurrence of a problem to apply their problem-solving skills rather than preventing or eradicating potential problems using trend analysis and problem prevention strategies.

We know that potential problems that convert into actual problems can and do hurt the businesses and peoples lives. Unfortunately, we tend to allow reactive management to flourish.

People tended to celebrate solving existing problems over preventing emerging problems from ever occurring.

Fixing a problem after it occurred makes no sense

Let us use crime prevention and employee fraud as examples to show that fixing a problem after it occurred makes no sense.

Example 1 — Crime prevention

Here are some questions to ask ourselves.

Is it better to:

- Beef up resources in the investigation function of a police force than to put our energy and tax payer’s funds to focus more on crime prevention?

- Prevent a crime from occurring than to catch the crooks after a crime has been committed?

- Tell people to secure their property and keep vigilant than to secure a legal conviction of a thief? (It has been reported in the UK that the chances of a theft resulting in a charge have halved, from 10.8% in 2015 to 5.4%, and from 2.6% to 1.3% for personal theft.)

It is without a doubt that it is easier and less costly and labour intensive for us to prevent a crime than to secure a legal conviction of a thief.

Prevention is better than a cure. There is wisdom in this age-old saying.

Example 2 — Employee fraud

US$42bn is the total fraud losses reported by 5,000 respondents across 99 territories about their experience of fraud over the past 24 months, according to PwC’s Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey 2020.

So, is it better to prevent employees from intentionally defrauding their employers than to spend time and money catching fraudsters and prosecuting them in the courts?

Over 40% of all potential fraud has been detected by employee tip-offs. Organisations with external hotlines (a prevention strategy) are much more likely to catch fraud by a tip and experience frauds that are 41% less costly and detected 50% more quickly.

But why wait for problems to arrive before solving them?

There are many reasons why people wait for problems to arrive first before taking any action. They include:

- Fixing a real or existing problem energises people. There are the adrenaline rush and glamour in overcoming a crisis.

- There is money to be made in solving a pain that people are experiencing — doctors, plumbers, turnaround specialist, etc. What’s more, it is easier to solve a known pain than a potential pain. It’s easier to locate the pain.

- It is also easier to justify a financial expenditure to fix a broken thing than to write a business case to solve a potential problem that may never eventuate at all. It is hard to justify the cost of preventing something that has yet to occur.

- People love to celebrate problem-solving achievements over problem prevention non-event. We can quantify the achievements — eg. we saved $200K, etc. There is no tangible event or achievements to link any celebrations to as it has been ‘neutralised’ before it ever materialised. The achievements of a solved problem are hard to quantify.

- Context matters. We know that people may do things differently at work from how they would at home. So, it is hard to pinpoint exactly when a problem could arise.

- “One death is a tragedy. One million is a statistic.” When risks are presented as real, we tend to emotionally feel and take action. People give more money to help one or two identified orphaned children than to help “all those orphaned children all over the world”. A problem that has occurred feel more real than an abstract problem that may never materialise.

- We worry more about risks that threaten us directly than risks that only threaten others. For example, while the majority of people believe that climate change is real and already happening, many aren’t willing to do much. A real problem that has impacted our hip pocket or caused pain to our body now requires our immediate attention and action.

- People are overly optimistic about things when they are far enough in the future. “She’ll be right, mate” is a frequently used idiom in Australian and New Zealand culture that expresses the belief that “whatever is wrong will right itself with time”, which is considered to be either an optimistic or apathetic outlook. When we can’t see the details and appreciate the future outcome, it is easier to talk about now.

The compliance games we play

We tend to focus on immediate threats that are occurring now in front of our eyes rather than on risks or events that are far in the future.

If we have determined that a severe pandemic is a once-in-a-century event (which is not), then this particular risk event would be logged in the organisation’s risk register as a high-consequence, low-probability event.

Organisations often focus on probability rather than on the consequence. It is our human tendency to be overly optimistic about future things and events.

We can mistakenly see this “once-in-a-century likelihood” as meaning that this event will occur many years into the future and it could, therefore, be disregarded.

This tendency has resulted in many organisations, and even governments, failing to take high-consequence, low-probability events as seriously as they should. There is a failure to plan, a failure to prevent a problem or to prepare themselves.

But do follow the trends and tell-tale signs

The first case of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was detected in Wuhan city in China sometime in December 2019.

On 30 December 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issued an urgent notification to medical institutions under its jurisdiction, ordering efforts to appropriately treat patients with pneumonia of an unknown cause. It appears to be viral and patients are to be in isolation.

In the meantime, Government officials in Hong Kong and Taiwan detailed what’s known from mainland China sources and infectious disease news on sites such as FluTrackers, Avian Flu Diary and ProMED Mail.

Together with the previous history of pandemic outbreaks, there were already clear signs that a crisis of this magnitude would likely eventuate (rather than unlikely) in the future for organisations and governments to deal with. It wasn’t a question of if, but when.

Unfortunately, in typical human reaction and complacency, many people adopted a wait-and-see or do-nothing approach. They waited for the problem to crystalise or materialise at their doorstep before any action was taken.

Many people cited the need (aka excuses and incompetence) to get more certainty, clarity or confirmation about the extend of the problem. It does sound good at the time.

But the speed at which the coronavirus spread gave not much time for decision-makers to solve the problem or react to the crisis. And many started blaming China instead of taking responsibility for their inaction and incompetence!

As we have experienced, the majority of governments and organisations were caught off guard, unprepared. Many paid a premium price for their inaction.

The lock-downs that hastily came thereafter to mitigate the public health crisis have only triggered severe recessions and unemployment in many economies.

Millions of workers became unemployed overnight.

Many businesses had to close temporarily or permanently.

Millions of livelihoods were destroyed.

Overnight, many economies were plunged into darkness and severe public debt that will burden many generations to come.

There is enough information out there to know that a problem is already coming

Let us look at project management as an example of how we can use existing or available information to prevent problems from ever occurring.

According to a 2017 report from the Project Management Institute (PMI), 14% of IT projects fail. However, that number only represents the total failures. Of the projects that didn’t fail outright, 31% didn’t meet their goals, 43% exceeded their initial budgets, and 49% of projects were late.

Problems about product quality and slipping deadlines are common in product development programs but, the context varies. By anticipating known problems and developing out of the box solutions, we can effectively prevent many of the known problems from occurring and reaping the benefits.

To complete a project successfully, we need to put in place plans or mitigations to address the key causes of many project failures even before projects commence. These known failures have been well documented. We can’t say that we did not know about these potential causes of project failures.

This can lead to the top-down approach to managing project risk rather than the bottom-up approach of risk identification and management using ISO 31000 risk management process.

Develop a checklist of known causes of projects before the commencement of the project. Apply this checklist by implementing and monitoring mitigations well before project problems arise in the future. Problem prevention should be the focus instead.

Granted, no one can accurately predict the future. But in the business world, things are a bit more predictable as long as you take the time and effort to carefully assess known variables and apply past lessons.

Crises seem to erupt quickly, but most take years to emerge

Anthony Fitzsimmons and Derek Atkins, in their book, Rethinking Reputational Risk, wrote, “Typically a crisis has multiple root causes, often systemic, that remain unrecognised and unmanaged but gradually accumulated over the years to make the organisation vulnerable to crises generally”.

Unfortunately, leaders and managers are often unaware that there is an incubation period between the circumstances leading to the risk outcomes, and the actual occurrence of the risk event. This can lead to failure to understand the actual cause of the risk event that the organisation is now experiencing.

Long incubation periods of a known uncertain event (risk) can also lead to complacency. The wait-and-see approach is not a problem-prevention solution.

Everything follows a pattern or trend. There is an incubation period for risks and problems to develop gradually over time. They will crystalise or materialise via a trigger event. Certain characteristics will slow emerge along the way, over time. Knowing where to look and what to look for will be the keys to pre-empting the problem before it occurs and softening its impact.

Minimising the chance of potentially unknown problems from arising

There are several things we could do to minimise surprises:

- Keep an open mind, give yourself time to react and think for yourself — Weighing the risks, benefits or even scientific details about mercury in swordfish, or nuclear versus fossil fuel power, are trickier calls. They demand a little more careful thinking. Keep an open mind so that your feelings and instincts don’t smother what the facts and evidence may have to offer. Get more information especially from neutral and reliable sources. Apply a little scepticism to the information and trends. News media tend to make things sound more dramatic than they are. Just assume that you don’t know as much as you need to know to make a good decision. Making better decisions is about learning something new, not just reinforcing what you already know and believe. Challenge your thinking.

- Cultivate open and honest communication — Be open to any news, information or trends. All news is good news. Encourage an open flow of information between team members and stakeholders. Don’t shoot the messenger, ever. Celebrate a transparent, open and honest communication culture. this will help everyone involved make solid contributions to a discussion.

- Encourage constructive feedback and opinions — Celebrate the diversity and inclusion of views, opinions and insights. Hire a diverse range of team members to get a rich exchange of ideas and opinions. Blind spots are everywhere.

- Learn from past mistakes and decisions — Sometimes, the answer to a current or potential problem will often resemble that of a previous problem or experience. Keeping thorough records and applying lessons learned can be vital to your success. It provides valuable insights and learnings for future decisions.

- Encourage collaboration — Getting input from people within and outside your team can be an excellent method for uncovering possible future problems. Celebrate diversity and inclusion!

- Imaging the outcome and identify barriers to achieving that outcome — This anticipation is the core of the risk management process. Identify any known uncertainties and implement mitigations to increase the likelihood of your success.

- Always test things out — Some changes may be necessarily done on the fly. Constant testing and evaluation will help to uncover hidden issues in an agile or flexible way. Assumptions that don’t hold true will become risks that must be acted on.

- Develop protocols for listening to alarmists (even though we won’t necessarily act on their warnings). Avoid knee-jerk dismissals of improbable warnings, trends and opinions. Prepare drills or scenarios for helping decision-makers anticipate the consequences of potential events and to gauge their significance and impact. If the warning has merit, take more notice and find confirmations. Deploy technology and data analytics to focus data-gathering on observed warnings.

- It is not about more data or information, but what you do with it that matters — While we may want more information before we make a decision, this wait-and-see approach could be detrimental. Knowing the point of the sufficiency of information is the key to an effective action-taking.

The bottom line — the complacency of decision-makers

The belief in black swan events comes with a delusion that once informed about a known uncertainty or threat, we will expeditiously take action. But we know that this isn’t true in practice.

The coronavirus (COVID0–19) pandemic was not an unexpected event. Alarm bells were already starting to ring in January 2020. In fact, alarm bells have been ringing well before 2020 with the numerous pandemics that the world has encountered and experienced. Many people have died from these pandemics.

Governments and organisations took the wait-and-see approach to problem-solving. Not many took immediate action to prevent the problem from occurring or planning for the inevitable.

When the problem did show up at our doorstep, everyone scrambled around frantically for answers and solutions. By then, it was too late. The coronavirus was unstoppable, especially in an interconnected world we lived in.

Many started to blame China as a way to divert attention away from their incompetence, complacency and inaction. Excuses started to emerge thick and fast.

Living in a fragile interconnected world — the proliferating of global networks, supply chains and interdependencies— have caused a severe worldwide domino effect that no one can stop. This pandemic spread like wildfire around the world. It has caused the greatest danger to our survival!

From my perspective, the problem isn’t a lack of data about known uncertainties and trends. It is just the complacency and inaction of decision-makers. Blaming others and giving excuses are just smokescreens for incompetent leadership.

Professional bio

Patrick Ow is a strategy execution specialist, corporate facilitator, personal coach, educator, and Chartered Accountant with over 25 years of international risk management experience.

He helps corporate executives and individuals execute their strategies and personal plans to get breakthrough results using The 7 Habits of Successful Strategy Execution. Visit https://executeastrategy.com or email patrick@executeastrategy.com for details.

Patrick has authored several eBooks including When Strategy Execution Marries Risk Management – A Practical Guide to Manage Strategy-to-Execution Risk (available in Amazon).

In addition to his professional work, Patrick has a personal passion for preparing individuals for the future of work.