Despite our collective educational establishments that purport to teach so that people can learn, ‘education’ is not necessarily learning. Mark Twain wrote disparagingly that “Education consists mainly in what we have unlearned” and also that he never let schooling interfere with his own education. Education is not necessarily knowledge and real learning comes from the application of theory tempered with experience which will make for better decisions and better outcomes. Benjamin Franklin’s words from over 200 years’ ago “Tell me, I forget. Teach me, I remember. Involve me and I learn” still ring true today.

Despite our collective educational establishments that purport to teach so that people can learn, ‘education’ is not necessarily learning. Mark Twain wrote disparagingly that “Education consists mainly in what we have unlearned” and also that he never let schooling interfere with his own education. Education is not necessarily knowledge and real learning comes from the application of theory tempered with experience which will make for better decisions and better outcomes. Benjamin Franklin’s words from over 200 years’ ago “Tell me, I forget. Teach me, I remember. Involve me and I learn” still ring true today.

The more we are involved the more we learn and consequently we are all on some form of learning curve. Projects, being unique undertakings can be full of eventualities that require either new learning or an application of previously gleaned knowledge from some earlier experience. This humble realisation is rarely acknowledged and oftentimes conveniently forgotten by those who make decisions on the fly in the hope that their decisions will be correct, their hopes will eventuate, and they will not have to walk-back on their words. A line from the movie Apollo 13, “Let’s not make things worse by guessing”, indicates that even NASA working at the extremes of earthly risk try not to gamble and decide on the basis of hopes and prayers.

Learning Curves

A learning curve is the process whereby people develop a skill by learning from their mistakes. Nelson Mandela famously said “I never lose. I either win or learn.”; and this sums up learning. There are hundreds of quotes on the subject but, in summary, real learning comes from a combination of experience and failures. Henry Ford’s advice that “Failure is simply the opportunity to begin again, only more intelligently” hits the nail on the head when he referenced ‘intelligence’ which is the application of knowledge and knowing why things went wrong and addressing those wrongs to make a right.

“Nobody knows anything…“ said the moviemaker William Goldman somewhat derogatorily and then qualified it with “…Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.”

The making of a motion picture is one example of a project. The outcome of a movie and its receipt by critics and audiences may be a guess, but the directors, producers and writers alike will learn from any box-office flop and, hopefully, not repeat it. It’s the same in all walks of project management life.

In an essay by Leonard Reid on Adam Smith’s 1776 monumental text, ‘The Wealth of Nations’ it is explained that not one person on Earth knows how to make a pencil. The number of people, trades and skills required is beyond any individual but mankind can and does through the technological and economic collaboration of Smith’s “Invisible Hand”. In the world of projects with nobody knowing everything and most knowing only something, projects can be made to come together; albeit some well and some not so well.

But when things do go wrong “the learning curve” is often the reason given for any delays, making initial wrong decisions, and failure. It’s always easy to be wise after the fact and the ensuing blame in the inevitable witch hunt for the ‘guilty’, or those who would speak with a voice of reason, are a far cry from learning except for learning to keep one’s head down.

These ‘curves’ of learning are described in many ways and euphemistically are akin to hill walking. We use descriptors such as short and steep (having to learn quickly or with difficulty), or shallow and long (learning more slowly or needing more time). However, for some the curve can be flat as learning is put to one side on a plateau of complacency while for others it’s a downhill slope as clots thicken. Of course, there is the ‘unlearning curve’ where previously held beliefs or knowledge are analysed and reconstituted so that there is a true understanding rather than a superficial learning of ‘facts’ by rote and blindly following established norms.

Competence & Confidence, Enthusiasm and Experience

When confronted by an unplanned for, but not necessarily unknown situation, a decision maker can be faced with a dilemma; a quick decision in an absence of knowledge or a correct decision based on experience. The off-guard decision maker caught in the metaphorical headlights of a looming crisis is then required to wing-it with enthusiasm with a leap of faith after a cheap and not necessarily cheerful assessment of the situation. Of course, they can ask for assistance but in a toxic environment their career prospects may be at risk. There is always the ‘do nothing option’ and the hope that problems will go away but this, unless it’s a conscious decision with a justifiable position, may also result in career suicide.

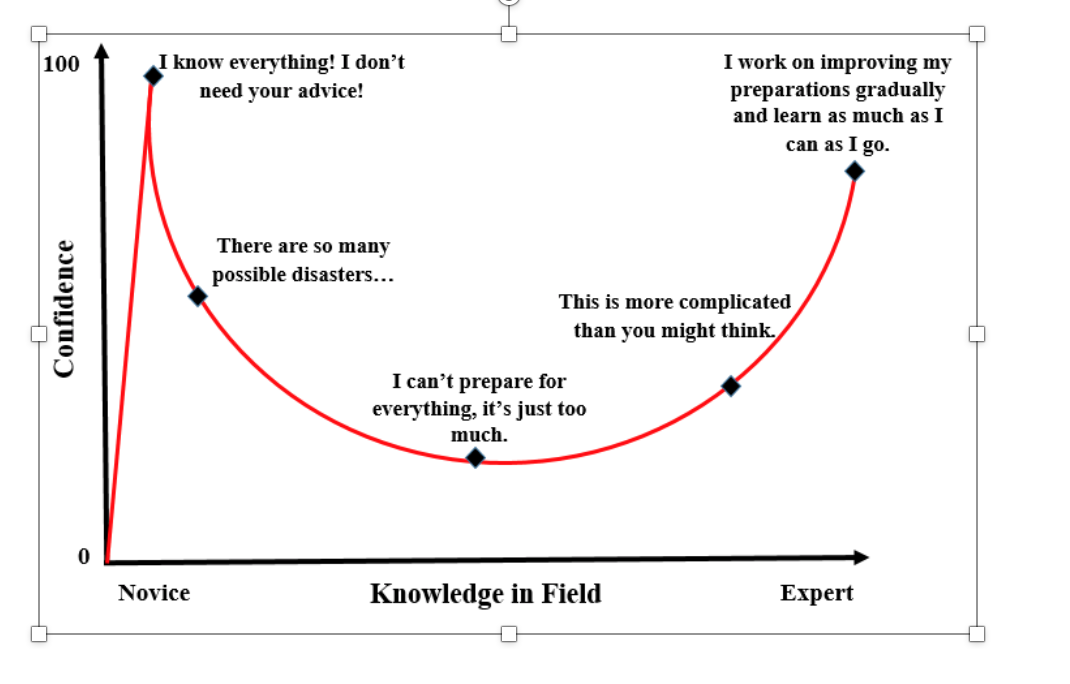

In the enthusiasm that an untoward situation triggers, or possibly the well disguised panic that ensues, rapid assessments are made. “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing” and the Dunning–Kruger effect should be heeded.

Overconfidence results in a delusion that everything is known but, as with most subjects after the initial confidence there is a realisation that there is more to a situation than meets the eye. This is followed by a further realisation that things are more difficult than they first appeared. From this depth of despair eventually comes the enlightenment that although there is a complication, learning is essential for competence.

An early decision based on overconfidence and enthusiasm is unlikely to demonstrate competence. Alternatively, a voice of experience that would ask the right questions of the right people in in doing so could well obviate the risk of an inappropriate or even wrong decision. But where does this voice come from?

If decision makers surround themselves with an entourage of ‘yes men’ then a collective lack of knowledge or competence can certainly speed up the rate at which everything is “known”. The risks of an overconfident project team who are learning ‘on the job’ can be far reaching and far from reasonable and rational. The ‘voice of reason’ may seem like a cry in the wilderness and far from the madding crowd but the problem is, will it be heard and even more problematically, will it be heeded?

Unlearning Curves

Although learning starts with education our first lessons are about the fundamentals; they are ‘elementary’ and never forgotten and are the foundations for the progression of learning and developing intelligence and intellect. This development is influenced by other things including who teaches, when and where it was taught or learned, and the ‘school of thought’ under which learning takes place. How we are taught and by whom can depend on beliefs and assumptions, and although there are many different approaches, no one approach is right despite zealous advocates of their singular view of ‘the right way’.

We learn that sometimes what we have learned is not applicable or, and hopefully rarely, we find it’s just plain wrong. It’s then that we need to change our approach and unlearn. As with any bad habit there is no point in holding onto it just because you spent a long time doing it. Unless we ‘unlearn’ and try different approaches we will not be able to sort the wheat from the chaff. Of course, when we must ‘unlearn’ good things because of some toxic micromanagerial idiosyncratic and blinkered approach then this is far from healthy and a basic travesty.

The ‘learning curve’ may be seen as a risk but the ‘unlearning curve’ is an opportunity to put wrongs right. The challenging of “conventional wisdom” and “established norms” in the light of situations that arise may be necessary. After all we probably ended up in that situation in the first place because of a prevailing culture and routine processes or adopting a “just do it” and ‘learn as you go’ entrepreneurial approach and hoping for the best.

Unlearning is difficult as it not only challenges the status quo but requires a change of approach, attitude and mindset. This typically takes time, but can be expedited through the positive experience of some mind-blowing revelation as the lights are suddenly turned on or, more often through mortification when the proverbial penny drops. Some people, as with marketing will be early adapters who quickly follow the innovators while the diehards who hark back to the ‘good old ways’ will be the laggards who may adversely influence the majority of acceptors be they early or late.

Conclusions

Nobody knows everything…but that doesn’t mean to say that you can’t find out and engage those who will know and allow the risks associated with a potential lack of technical, managerial or societal knowledge to be mitigated.

It takes time to learn and how to learn. A learning curve may be associated with a particular project but also applies to personal and corporate learning. The analogy with hillwalking is true and often the clutter of knowledge that is collected hampers our ascent. In an environment of incompetence, those who believe they have learned it all may stultify the further learning of others. This can obviate the ability and willingness to adapt and learn more; in the battle for survival of the fittest the risk of extinction and failure may well become an inevitability.

The clutter of corporate and personal knowledge may be seen as an enterprise asset but if it prevents further learning then some unlearning may be necessary. Lessons learned in by-gone projects could be history and despite being heritage may well be outdated and inappropriate. Learning new knowledge and adapting it to new projects rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach may be required. ‘Unlearning’ may be essential in order to create a leaner and meaner approach to dealing with unforeseen or surprising situations and enabling proper and timely decisions.

If we don’t learn and unlearn there could well be some failure in one form or another. On a positive note, and in the words of the entrepreneur Malcolm Forbes: “Failure is success if we learn from it”. However, in the cold light of projects, failure is rarely understood to be a learning opportunity and whichever learning curve you are on, the acquisition and application of necessary knowledge is not only steep but oftentimes precipitous.

Bio:

Malcolm Peart is an UK Chartered Engineer & Chartered Geologist with over thirty-five years’ international experience in multicultural environments on large multidisciplinary infrastructure projects including rail, metro, hydro, airports, tunnels, roads and bridges. Skills include project management, contract administration & procurement, and design & construction management skills as Client, Consultant, and Contractor.