Teams, they are everywhere; sports teams, project teams, political parties, rock bands, military units, the list goes on. The team isn’t just about the people in the limelight it’s also about the backroom boys and girls who provide logistical, technical, administrative, and sometime moral support to the front men and women. Even the lone competitor or the one-man-band needs some support; everybody needs somebody sometime.

Teams, they are everywhere; sports teams, project teams, political parties, rock bands, military units, the list goes on. The team isn’t just about the people in the limelight it’s also about the backroom boys and girls who provide logistical, technical, administrative, and sometime moral support to the front men and women. Even the lone competitor or the one-man-band needs some support; everybody needs somebody sometime.

Within the variety of teams there is a spectrum of performance. We have so called ‘high performing teams’ at one end and ‘low performing’ ones at the other and a range in-between including fun, functional, dysfunctional, and ‘you get what you’re given’. High performing teams generally obtain better results than the low performing ones, but all teams obtain some sort of result. That is not to say that just because they are not high performers doesn’t mean to say their results aren’t good.

Our ‘high performers’ are made up of people with specific roles and complementary talents and skills who are aligned with and committed to a common purpose. Through collaboration and innovation, they consistently produce superior results by focusing on the tasks in hand. This focus is obtained by extinguishing radical or extreme opinions that could be damaging to progress and barriers to performance are effectively removed. An important part of such teams is the element of trust between members and the adoption of a participative leadership style. But why can’t teams with these qualities perform more highly, or more consistently than their possibly not-so-gifted competitors?

People! …Yes, plain and simple, people. People make up the teams, people manage them, people lead them and people judge them. The relationships between team members, the glue that binds them and the oil that allows them to move is about people, the trust between them, the tolerance they have for each other and the way in which leadership works for them.

Trust

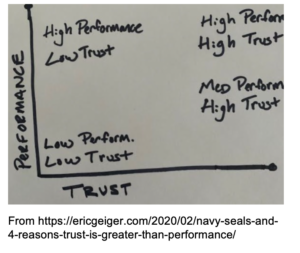

The US Navy SEALs (SEa Air & Land) have some very, very competent people and their teams work because of the character of those people. They even have a graph showing the relationship between the ‘competence’ of people, i.e. their performance, and the ‘trust’ they have won from, and share with their colleagues.

It may not be surprising to some, but there is a preference to have a team with medium performers and a high trust between team members than high performers with low trust. High trust enables rapid and effective communication, less time is spent explaining and discussing and, perhaps trying to find a hidden agenda or covering it up. ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going’ and trust identified in less arduous times is a prerequisite when situations get harder. Trust also allows for frank and unguarded relationships leading to, at least at some time or another, fun

It may not be surprising to some, but there is a preference to have a team with medium performers and a high trust between team members than high performers with low trust. High trust enables rapid and effective communication, less time is spent explaining and discussing and, perhaps trying to find a hidden agenda or covering it up. ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going’ and trust identified in less arduous times is a prerequisite when situations get harder. Trust also allows for frank and unguarded relationships leading to, at least at some time or another, fun

Trust is about having confidence in other people. It’s not necessarily about respect as respect can be demanded through positional authority and is based on how a person is perceived and thought of. We can respect some people and their opinions but not necessarily trust them. But trust must be earned as should respect, they are not gifts.

Trust requires an individual to be competent and know where and when they are ‘not-competent’, to be empathetic not necessarily sympathetic, and be able to instil confidence. It also requires an ability to look after other people’s best interests as well as the collective interests of a team and be responsible and accountable for their decisions. However, and possibly above all else, it requires honesty and ‘straightness’.

Trust can be hard to win, easy to lose, and once lost, possibly irrecoverable. Time may heal all wounds, but memories can last for generations and trust can take a lifetime to repair. People who trust each other tell their version of the truth and are unafraid to argue it. They know that through active communication there will be, at least, commonality of purpose. On the other hand, however, lying breaks trust and, even if it can be repaired, the break will always be remembered and may be a long-term point of weakness.

Tolerance

Tolerance is advocated everywhere. In todays’ self-proclaimed rainbow age of inclusionism as well as policies against discrimination based on age, disability, social background, race or religion, a team may well be diverse. But when it comes to team work these things shouldn’t matter; they may matter at a corporate level so that quotas are met and a KPI is ticked off, but working teams require working people no matter who or what they are or where they are from socially or geographically.

Tolerance is about interaction between people and ‘getting along’. People must be willing to interact so that a team ‘gels’ otherwise there will be conflict; not necessarily out-and-out hostility or physical threats but a failure to communicate rationally. Team members must be able to listen to the views of others and be prepared to have constructive debate leading to collaboration rather than destructive argument leading to conflict and ostracization. If the latter occurs a team will not be a team and performance problems may well ensue.

We all make mistakes, and nobody (despite personal opinions) is perfect. Similarly, in a team, perfection is a difficult call and transgressions will be made. In high performing teams these transgressions will be seen as an opportunity for the team to come together and learn rather than cast blame and look for scapegoats. These lessons learned will ensure that mistakes, while possibly being forgiven will, unlike breaches of trust, not be forgotten.

Tolerance doesn’t mean that things should just be tolerated – i.e. allowed to happen without any interference. Ignoring somebody or something that’s wrong won’t make it go away and it must be challenged and corrected. But, in any group of individuals some will be better than others at some things and, if a team is well structured the weaknesses of some will be offset by strengths from others

Leadership

Leadership, according to Field Marshall William Slim is an art. It’s a function of a leader’s spirit, personality and vision coupled with an ability to and an inherent fitness to command. There are many other views on the topic and most emphasise the need for individual strengths and ‘doing the right thing’ rather than the more mechanical functions of management and ‘doing things right’.

A leader does not always have to be present, but their persona must and, using Slim’s view, their spirit must be conveyed. Spirit is the essence of life, and just as when a life is lost, leadership becomes most significant when it is absent. Leadership is essential and it doesn’t matter how many people are in a team or how many processes and procedures are adopted, we should remember the words of the Greek playwright, Euripides, 24 centuries ago: “Ten good soldiers, wisely led, will beat a hundred without a head”. It’s all about leadership and ‘good’ people who can both trust and tolerate each other.

There is often talk in many organisations of ‘the leadership team’ which is also just ‘a team’ despite being made up of appointed leaders from other, subordinate teams. The same elements of trust, respect and tolerance are required and perhaps more so. Even the leadership team requires ‘leadership’. Leadership, as with management by committee may arrive at a solution, or a hybrid of solutions eventually. However, time waits for no committee to come to consensus and a leader’s intervention will inevitably be required if a decisive decision is to be made in time.

The leadership of a team can sometimes be through participation but on occasion a ‘leader’ on a metaphorical horse stepping into the breach is required to take command. If leadership for any reason is absent this leads to factionalisation, petty politics, and possibly discrimination against individuals whose views are different. Once the rot sets in it can be difficult to stop and a team’s performance will drop, if not plummet.

Conclusions

When forming a team it’s important to remember that, despite being ‘old hat’, the 1965 observations of the psychologist Bruce Tuckman regarding the developmental sequence of forming, storming, norming and performing still rings true; it takes time to mould a team and we still don’t have an AWAM (Add Water And Mix) solution . It also takes time for people to get to know each other how they work. It also takes time to develop both respect and, possibly above all, trust.

Trust and respect are complex values and feelings based on belief and emotion, but they tend be binary; we either do or we don’t; it’s not about liking somebody or even friendship. Without trust and respect the chances of people tolerating each other will also be sorely tested. Tolerance has its limits, particularly if the truth is hidden or cocooned in deceit. When the truth is lost then trust quickly follows; the once tolerant become intolerant and dysfunctionality can quickly set in.

Dysfunction can be mitigated when there is leadership that instils a belief in what is being done and why it’s being done so that a team spirit can be nurtured and developed. Of course, if weaknesses occur that cannot be offset against strengths then any ‘dead wood’ will have to pruned so that the rest of the team is not exposed to any decay.

Any team will have strengths and weaknesses, albeit comparative, but in a good team the strengths should mitigates the weaknesses and members will be mutually supportive. As Aristotle purportedly recognised over 2,300 years ago, ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’ emphasising the value add of teams rather than a group of individual individualists.

Bio:

Malcolm Peart is an UK Chartered Engineer & Chartered Geologist with over thirty-five years’ international experience in multicultural environments on large multidisciplinary infrastructure projects including rail, metro, hydro, airports, tunnels, roads and bridges. Skills include project management, contract administration & procurement, and design & construction management skills as Client, Consultant, and Contractor.