Cultures rise and cultures fall. That’s a fact. We’ve had the Aztecs and Mayans of Central America, the Hittites of Asia Minor, ancient Egypt and its pharaohs as well as classical Greece and the times of Alexander the Great. Genghis Kahn and his Mongol hoards created an empire and cultures that once dominated much of the known world.

Cultures rise and cultures fall. That’s a fact. We’ve had the Aztecs and Mayans of Central America, the Hittites of Asia Minor, ancient Egypt and its pharaohs as well as classical Greece and the times of Alexander the Great. Genghis Kahn and his Mongol hoards created an empire and cultures that once dominated much of the known world.

In more recent times we’ve experienced a few short-lived cultures. Some, albeit too politically and morally sensitive to mention, only lasted for a matter of years despite proclaiming that they would last a millennium.

The common denominator in these ancient and modern cultures is a dependence on some individual or another who established the culture and maintained its evolution be it successful, unsuccessful, positive or negative. When maintenance stops, just as with a machine it will fall into disrepair and ultimately break down. Breakdown is a result of external forces leading to abandonment, or being banned, or engulfment. It also comes from within as cultures wane rather than wax. People cling to memories of greatness and bask in their own cultural complacency.

But it’s not just civilizations that come and go, it’s also businesses and projects. When an inspirational founder or rejuvenator leaves then the essence or spirit of an organisation may well leave with them. Wannabee successors may try to emulate their predecessor, but they aren’t the real thing and may not fill the shoes. Copies may work for some, for others it’s a poor substitute, and for others it’s just a forgery. Sub-cultures and cliques can form unless an organisation’s culture has sufficient capacity, or mass, to accommodate the change. If it can’t then an organization may well stagnate and, like other bygone cultures, fade into obscurity.

Culture & Cultural Mass

Cultures are about behavior, but cultures are initiated by the attitude of those who create them and about whom stories are told, and identities are formed. Behaviour can be easy to copy; adopting the corporate dress codes, adapting to idiosyncratic rituals trappings and jargon help to develop a culture and people can easily go with the flow of these outward trappings.

Such branding however is not attitude; attitude drives behavior that inevitably leads to consequences both good and bad. Behaviour can, in some circumstances, be changed. For example, most people who join the armed forces or other disciplined forces change from civilians to soldiers. The prison system attempts to change criminal tendencies, but the hardened criminal may never really change. As they say, “once a thief, always a thief”.

However, outside of prison and army boot camps it’s a difficult ask to change the attitude of those who would prefer to go with the cultural flow of an organisation in blissful unawareness that the culture is changing or has changed. There needs to be some mass, some anchor that realizes change is occurring and has the attitude to address it. This is about the wherewithal to realise that culture needs maintenance and doing something about it. Such a stance can be difficult and is not for the fainthearted who prefer to follow rather than lead or don’t know how to get out of the way.

Culture must adapt to the consequences that arise from behavior. Cultures that are self-satisficing become arrogant and believe in their own superiority and ability which results in arrogance and satisfactory underperformance. BYOB in this case doesn’t mean ‘bring your own beer’ but “believe your own bullsh*t’. Attitude can be seen as a problem but when it comes to driving organisational performance and getting the best from people it’s all about attitude.

Indispensable & Indispensability

It is said that nobody is indispensable. If anybody’s ego grows to the point where they believe that they are then, as the late poet Saxon Nadine White-Kessinger allegorized, they aren’t,

Take a bucket and fill it with water,

Put your hand in it up to the wrist,

Pull it out and the hole that’s remaining,

Is a measure of how much you’ll be missed.

This is true but how often does a person leave an organization and the hole or gap they leave takes a long time to close or is never closed properly. It is not they who believe they are indispensable but the people around them who fail to fill the gap.

Some say that in any group some form of leader will take over but, and depending on the leadership style, or lack thereof, a subculture of just doing enough to get by or avoiding the spotlight of responsibility and accountability can develop. It’s under these circumstances that indispensability becomes an issue and the question of the dispensability of a key individual(s).

There are a couple of heuristics related to how people contribute; there’ the 1/9/90 rule and Price’s Law. The 1/9/90 rule, while related to social media networks argues that only 1 percent of users actively create content, 9 percent contribute by commenting or sharing and the other 90 percent are silent spectators. How often do we find that if the 1 percent who provide the drive leave then, at least for a while, the remaining 99 percent rudderless. In large organisations this “1 percent” is usually more than one person, but what about in smaller enterprises?

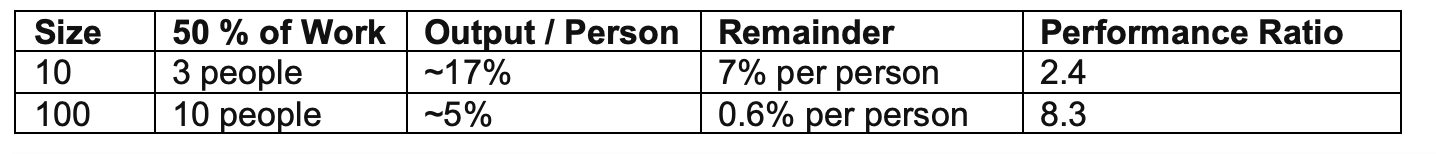

Here we have Price’s Law and that “the square root of the number of people in a domain do 50% of the work”. For example

If Price’s Law is allowed to rule, then we find that organisations will rely on a few good individuals rather than the entire team. A good team is greater than the sum of its parts. If organisations rely on a small “cultural mass” when one person leaves the mass may well become insufficient to maintain the whole culture…just like yogurt!

Performance – the Conclusion?

Organisations and teams, and even nations, focus on their performance from either an inward perception or an outgoing one. How do they rank against their peers? How far ahead are they in terms of profit, GDP, market standing or ESG ratings? Is their share price increasing and are they in the ‘top 100’ in some financial rag or other?

Performance ultimately depends on people. People adapt to the environment in which they work and adopt the prevailing culture. A culture’s stability depends upon its “cultural mass”. If the mass is small and dependent on one or two individuals the culture and associated performance may not last. There may be some inertia should any leader or other figurehead leave but unless others with ability step-in, or step-up, then any inertia won’t last for long.

And if nobody steps in then factionalisation may become the order of the day. This leads to fractionalisation of the many and marginalisation of a few but ultimately the sum of the parts is less than the whole that it should be. The missing component of course is the critical mass that glues any entity together.

Long-term performance requires succession planning and either the grooming or acquisition of the right attitudes to maintain the cultural mass. In large organisations this may require questioning aspects of the culture but on smaller ventures with transient workforces then this can be critical to the shorter term performance of projects. But no matter what the size of the organisation your performance depends on your culture and maintaining its cultural mass.

Bio:

Malcolm Peart is an UK Chartered Engineer & Chartered Geologist with over thirty-five years’ international experience in multicultural environments on large multidisciplinary infrastructure projects including rail, metro, hydro, airports, tunnels, roads and bridges. Skills include project management, contract administration & procurement, and design & construction management skills as Client, Consultant, and Contractor.