Many years ago, while giving a presentation to representatives of the Chinese Finance Ministry my translator hit a bump as she attempted to translate something I was saying about accountability. I was a young consultant, fresh from a Chemical Industry career, and like all my fellow practitioners, I spoke accountability as a first language.

Many years ago, while giving a presentation to representatives of the Chinese Finance Ministry my translator hit a bump as she attempted to translate something I was saying about accountability. I was a young consultant, fresh from a Chemical Industry career, and like all my fellow practitioners, I spoke accountability as a first language.

I found it fascinating that a concept so basic and fundamental could seem so complex and difficult to understand in this foreign land and culture.

But that was long ago, and I am much wiser now. I now understand that it was never basic, never simple, and never easy to understand. Not in China and not anywhere. But darn it, it should be! A recent article about five factors affecting accountability triggered a search of what resources are available on the Internet about accountability.

Wow! It is unbelievable how much energy is devoted to the subject. There is a federal accountability act, provincial accountability laws, an accountability website, a citizen for accountability lobby group, an accountability research corporation, an accountability project, accountability courses, countless accountability bills, reports, studies, programs, services, documents, and posts and, of course, consultants. A search of images on Google yields even more mind-numbing visual representations. There are Deming cycles, pyramids, wheels, triangles, question marks. It looks incredibly complex.

None of these materials, however, clarify what accountability is or what it takes to establish it.

What it is, or should be

The very definition can undermine accountability.

The wiki definition of accountability is ‘…answerability, blameworthiness, liability, and the expectation of account-giving….’ The negativity underlying this definition is disheartening. If this is what accountability is, who on earth would want to accept it? After all, these are just synonyms for blame. Blame is the single biggest force driving efforts to duck, avoid, evade, divert, or subvert accountability. Any organization that uses this definition (do I hear ‘government’ here?) is almost certain to wrestle with establishing any accountability at all.

A healthier definition might be Webster’s, which defines accountability as, ‘…an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions…’ This is a little better, but still smacks of blame.

A positive perspective change everything

The preferred definition that I have used over the years is, ‘…. the act of determining responsibility for the results of actions – as a foundation for ensuring future success…’ The differences should not be too subtle:

- It is not about actions, but the results of actions (you can watch actions, but you have to measure outcomes).

- It is not about past results, but understanding how past outcomes can be used to improve future results (blame all you want, but the real purpose has to be change, not fault).

- It is not just about negative results, failures, but can be about positive results as well and can celebrate success as much as recognize failure. (There has to be an inherent fairness, a willingness to recognize success to be truly accepted).

This definition can be assigned to an individual, a group or an organization. It can be assigned by a second party, or it can be embraced by those performing the actions themselves. Most of all, it is NOT just about blame. When failure is indeed involved, large or small, accountability is, or should be, about understanding the root causes and making sure that whoever was involved does not make the same mistakes in the future.

The Basic Elements Are in Fact Very Simple

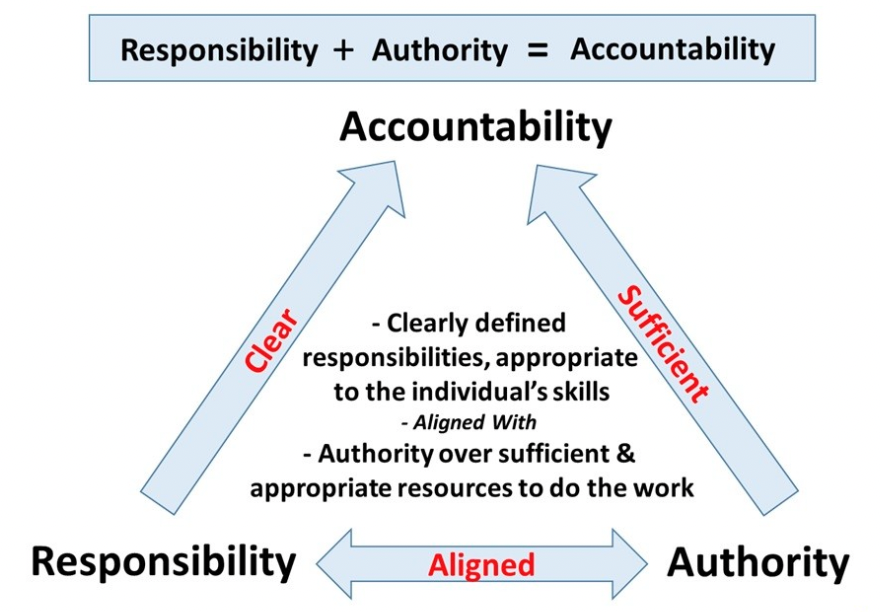

Clearly accountability can be made complex, but it does not have to be. In fact, the ultimate basis for accountability can be deconstructed down to two very basic elements:

- Responsibility: Before I can be truly accountable, I must first be clearly responsible.

- Authority: I can only be accountable if I am empowered with the resources necessary to do the work.

Both must be aligned. I often use this in a formula:

It is indeed that simple. But even in this there are layers that make it more complicated.

Responsibility

Responsibility requires clearly defined roles, but within which must be clearly defined performance expectations. The complicating factors are:

Responsibility for results must be unique in that more than one individual.

- responsible for doing something means neither will be accountable.

- Each job requires clearly defined performance metrics for each responsibility.

- Processes are required for setting reasonable, mutually agreed targets for those metrics.

- Mechanisms for capturing and reporting timely, accurate and relevant actual results against those targets within responsibility centers are essential.

- Most of all, responsibility needs to be aligned with skills and competencies.

In a world of flexible, agile organizations, perhaps the greatest barrier to accountability for performance is the ubiquitous job description term, “…and other duties as assigned….”. This is the ultimate accountability killer.

Common ‘responsibility’ gaps in accountability efforts

Organizations constantly wrestle with establishing accountability for performance, no where more so than in government with public servants. Things I have encountered in helping government clients establish accountability include the following.

- Responsibility is ad hoc, anecdotal, and casual, a result of long outdated (sometimes decades old) job descriptions.

There is no time for stuff like job descriptions. Managers just assume the employee knows what the job is today. More importantly, they assume that the employee sees it the same way, which is rarely the case, especially when something goes wrong. - Responsibility is shared, or worse, usurped by the very manager who would look for accountability.

Often the manager intervenes and takes on part of the role themselves, or directs so closely on what to do, when and how that the manager effectively assumes responsibility for the actions, and by extension accountability for the results. - Undefined work metrics, where the job tasks may seem clear but how they are measured is never defined.

Performance measurement might just be the fastest growing dimension of government management thinking today, but it is still in early stages and most government jobs have few metrics, and fewer still relevant. - Performance expectations are vague, absent, or unrealistic, with outcomes left unstated or goals unreasonable.

This is often the case where budgets are the only performance metric but are frozen or cut without changing expectations for service delivery. - Performance reporting in municipal government is still in embryonic stages compared to the private sector, with only the most basic level of responsibility accounting in many government organizations.

- Many still have the “I don’t need financial reports til September cause I have lots of budget for the year” attitude, but even with monthly reporting it is just dollars against dollars, with only very rare ability to match spending with service performance.

- The competency gap is a factor, not because staff are incompetent but because the world is changing so much and so fast that it is hard to find people with exactly the right skills for the current tasks, technologies, service expectations and resources.

It can be harder still to take the time to pull workers out of the daily whirlwind to make sure they are properly trained as the changes constantly shift what work is done and how.

How many of these might apply in your organization today?

Authority

Ultimately, you can be as clear as you want about what I am responsible for, but if I am not empowered with the resources needed to do the job, I will not, indeed cannot, be accountable for the outcomes.

- I must have sufficient resources for the tasks.

- I must have appropriate resources.

Common ‘Authority’ Gaps in accountability efforts

Many organizations get the responsibility part of the equation but fall apart with authority. It is not just a simple case of not giving enough money or people. It too can become more complex, with the most common situations described below.

- Cutting my staff but not adjusting expectations for results.

- Moving up my deadlines without recognizing that there is a trade-off – without additional resources, something won’t get done.

- Giving me additional tasks or pulling my staff off on other jobs without recognizing the impact on outcomes.

- Giving me outdated, ineffective or inappropriate resources and expecting them to do the job.

- Expected me to deliver but not letting me hire/train/develop the right competencies in my team (or myself) essential to the work; and

- Setting goals that require 2015 technologies but give me 1990 systems to achieve them. Any of these looks familiar?

Who is Most Often Accountable but Least Often Held Accountable?

I learned years ago that when staff reporting to me struggle or fail, the first place I should look for accountability is the mirror. What did I not do to make sure my staff could be successful? Was I clear what they were responsible for? Did I make my expectations for results clear? Did they know the results for themselves? Did I give them enough authority over resources? Where they the right resources?

All these things, which all relate to the details above for the two dimensions of responsibility and authority, are ultimately the responsibility of management. That doesn’t mean employees can blame it all on their bosses and not be accountable for results at all. It just means that they can only be accountable when their bosses have done their jobs properly in the first place. (Sounds like management heresy, doesn’t it? But I think it lines up perfectly with what Drucker said so long ago and so much better.)

Recap

So, how simple is accountability? Just a matter of aligning responsibility and authority. Ok, maybe a little more complex:

- Accountability requires clear responsibility with measurable, mutually agreed targets that can be reported against, assigned to employees properly skilled to do the work and empowered with sufficient and appropriate resources to perform the work.

Bio:

Dr. Bill Pomfret of Safety Projects International Inc who has a training platform, said, “It’s important to clarify that deskless workers aren’t after any old training. Summoning teams to a white-walled room to digest endless slides no longer cuts it. Mobile learning is quickly becoming the most accessible way to get training out to those in the field or working remotely. For training to be a successful retention and recruitment tool, it needs to be an experience learner will enjoy and be in sync with today’s digital habits.”