Risk is seen by different people in differing lights over a wide spectrum from the risk averse ‘riskophobes’ to the daredevils who are ‘riskophiles’. We also have those who don’t have a strong opinion or view regarding some risk or another who are fair game to risk extremists who attempt to push their views upon the masses and manipulate beliefs.

Risk is seen by different people in differing lights over a wide spectrum from the risk averse ‘riskophobes’ to the daredevils who are ‘riskophiles’. We also have those who don’t have a strong opinion or view regarding some risk or another who are fair game to risk extremists who attempt to push their views upon the masses and manipulate beliefs.

There is many a Chicken Licken who will advocate that the sky is falling, at least somewhere, or that the end is nigh as some superbug or other will end life as we know it. We have warmongers who rattle the cages of pacifists, pacifists who annoy the warmongers and, environmentally, there is the net-zero-carbon-lobby who oppose those who are right. The world is in a constant state of turmoil as the ugly head of some threat or other is quickly heralded by politicians, activists, or the media only to be countered by conspiracy theorists. If the appropriate level of fear or controversy isn’t established the threat is just as quickly forgotten.

If, or rather when, such threats be they real, false, or fake, lose their newsworthiness and become old hat then life becomes business as usual. New news is then ‘discovered’ to keep us human beings occupied and detract from our real purpose on the planet – whatever that may be. In the absence of any ‘real news’ we are fed with ‘shock-horror’ to distract us from dealing with the real risks around us.

“Elephant Runs Amok During Temple Festival”. “Great White Decapitates Diver”. “The Shuttle Explodes; All 7 Die”. Such shocking headlines are attention grabbing. They, almost immediately, capture our human interest in the macabre with an obvious risk factor.

Risk, strictly speaking, is the product of the probability of likelihood and severity of consequences. But the likelihood of many of us being exposed to sharks, elephants or space exploration is, statistically, low and for many of us so remote to be almost impossible.

The risk is obviously high, because of the consequences. Just because the consequences occur in a dramatic way doesn’t mean that the risk is any higher. Spectacular may be newsworthy but despite the newsworthiness these shock-horror risks are small. And when we consider the 8 billion of us on the planet, they are nothing to cause too many people too much concern.

Size Isn’t Everything

On the other hand, we don’t see headlines such as “Deadly Mosquitos Kill Millions” or “Hunger Kills Every 10 Seconds”. Elephant and shark attacks and exploding rockets are obviously more spectacular but the consequences are the same.

The Challenger shuttle disaster in 1986 was attributable to the failure of a 7mm diameter O-Ring. The O-rings are one of some 2.5 million parts in the space shuttle system and small. However, on that fateful day, the size of the media interest in the mission overshadowed the known risks of operating in the record low temperatures that prevailed. With the chance of an incident forecast at 1 in 100,000, what could go wrong…

The microscopic malaria parasite and endemic hunger due to ignorance, and sometimes ill will, are just as severe but they have the added side effect of a prolonged and suffering death. Risk is not proportional to size. The Pug, Frank, in the movie Men in Black astutely observed that “When’re you [humans] going learn that size doesn’t matter? Just ‘cause something’s important doesn’t mean it’s not very very small”.

“The Devil is in the detail” goes the saying. In the postmortem of any failure, we regularly find that the fatal flaw is down to some point of detail, a gap in some process, or the exercising of judgement based upon somebody’s perception of risk as opposed to context and perspective.

Perception & Perspective

The riskophile has the optimistic view that risk is something that happens to other people while the riskophobe is pessimistically paranoid. Both extremes don’t realise that Murphy’s Law is not selective as to who or what it governs, and this includes for opportunities!

Risk is not an exact science. The mathematical determination of probability and likelihood as well as the use of statistics and forecasting using past and current data may be exact and precise but it’s not necessarily accurate.

A ‘forecast’ is what should have happened if what actually happened didn’t. The correctness of any forecast and the decision made depend on how a decision maker perceives a risk, or opportunity, and when, how and from where it is seen.

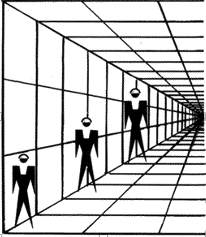

Take for example the three figures in the sketch – which is taller? Is the sketch to scale or is just an optical illusion created by an apparent vanishing point.

Time also puts risk into perspective. To use another quote from Men in Black “Fifteen hundred years ago everybody knew the Earth was the center of the universe. Five hundred years ago, everybody knew the Earth was flat, and fifteen minutes ago, you knew that humans were alone on this planet. Imagine what you’ll know tomorrow.”

The risks and perceptions of yesteryear are history, risk perspective changes with time. Mankind had delusions of galactic grandeur, we believed mariners would sail off the edge of the world, and we now realise we are an infinitesimally small player in the grand scheme of things.

Conclusion

On a more worldly footing, Stalin is attributed with saying, “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic”. This possibly addresses the human factor and perception. Many of us will appreciate the loss of a person or a few people but how many can grasp the enormity of hundreds of thousands?

Can we humans perceive where and who we really are and, on a philosophical note, what we are here for?

Arthur C Clarke wrote “I’m sure the universe is full of intelligent life. It’s just been too intelligent to come here”. Given how we, as the self-proclaimed dominant species on the planet behave, he had a good point. We take great risks in striving for earthly greatness but conveniently forget that, in the universal or possibly multiversal scheme of things, we are perhaps insignificant. Our perceived big risks are really very little and, while not exposed to elephants running amok, we fail to see the metaphorical elephant in the room.

Bio:

Malcolm Peart is an UK Chartered Engineer & Chartered Geologist with over thirty-five years’ international experience in multicultural environments on large multidisciplinary infrastructure projects including rail, metro, hydro, airports, tunnels, roads and bridges. Skills include project management, contract administration & procurement, and design & construction management skills as Client, Consultant, and Contractor.