Several years ago, I co-authored an article describing the growth of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) in government globally. (1) With the advent of COVID – 19, that growth has slowed. However, COVID – 19 has raised the issue of risk beyond the abstract. It has made it part of the dialogue worldwide. How much does wearing a mask reduce the risk of catching COVID – 19? How much risk is there to children if schools are reopened? What is the long-term risk to the economy of keeping it locked down?

Several years ago, I co-authored an article describing the growth of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) in government globally. (1) With the advent of COVID – 19, that growth has slowed. However, COVID – 19 has raised the issue of risk beyond the abstract. It has made it part of the dialogue worldwide. How much does wearing a mask reduce the risk of catching COVID – 19? How much risk is there to children if schools are reopened? What is the long-term risk to the economy of keeping it locked down?

These are common questions most people around the world ask almost daily. In addition, there is the Black Lives Matter defund the police movement in the United States. The response to which raises the question of public safety. At which level of police force reduction does the increase risk of crime and violence outweigh any social objective? The responses to these questions have significant implications for government policy and administration.

Even when the virus is under control because people have become conditioned to consider risks, the concern about risks will still be there. Moreover, the administrative process of managing the risks to the organization will become more of a focus. This is in part due to the need for governments to realign their activities with the reduced resources caused by the COVID – 19 shut down. For instance, the Brookings Institute estimates that revenue for state and local governments in the United States will decline $155 billion in 2020, $167 billion in 2021 and $145 billion in 2022. (2) At the same time that these declines are occurring, the demand that policing and other public services be reformed will likely continue. Consequently, ERM’s use will start expanding again in the public sector.

This reinvigoration can be seen in the issuance on February 4, 2021, of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s “Enterprise Risk Management Maturity Model”. Thomas Brandt, the Chief Risk Officer of the United States’ Internal Revenue Service, in his preface to the document indicates the reason and expectations.

“We are, of course, facing the enormous challenges of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which may have lasting impact on how we operations. We are also living through a period of increasingly rapid changes resulting from the digitalization of the economy, the emergency of new technologies and the challenges of climate change among others. … The ability to identify, understand and mitigate risks appropriately is more important than ever. My hope is that this new maturity model will help us in understanding our capabilities in this area in an objective and testable manner, to provide staff and senior leadership with an overview of their administration’s maturity level, including in comparison to their peers, and to inform decision-making going forward.” (3)

Also, in 2021 the American National Standard in conjunction with ASQ published “Guidelines for evaluating the quality of government operations and services”. (4) While the guideline stresses quality management, it contains a risk maturity standard.

These two guides demonstrate that ERM is being pushed in government. But the administrative mechanism management uses to encourage ERM use will help determine how quickly and where ERM spreads.

Oulasvirta and Anttiroiko in a study of ERM’s use by local government in Finland, (5) determined ERM was not widely used. The slowness of its spread is related to a lack of belief in its viability and a lack of a mandate.

This piece looks at the mechanisms used to influence ERM’s adoption by local governments in two Australian states. The states are New South Wales, and Tasmania. They represent slightly different approaches to the implementation of ERM. New South Wales is mandating that local governments adopt ERM. Tasmania is using the encouragement approach.

To provide more context to the framing of the ERM process in each state, it is important to look at what is happening with respect to ERM’s application at the Australian Commonwealth level.

While the focus of this piece is on government, it should be noted that issues related to adoption are often generic. Thus, the private sector can learn from the experiences of government.

The Commonwealth’s Application of ERM

In 2013, the Commonwealth of Australia adopted the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The act focuses on “governance, performance and accountability of Commonwealth entities”. Specially the focus is on the use and management of public resources.

For instance, Division 2 Subdivision A 16 Duty to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control, indicates that Commonwealth entities must establish and maintain:

- “an appropriate system of risk oversight and management for the entity and

- an appropriate system of internal control for the entity; including by implementing measures directed at ensuring officials of the entity comply with the finance laws” (6)

The Act covers the Commonwealth, and all state, territorial and local governments within the Commonwealth. In 2014, the Australian Government Department of Finance issued “Commonwealth Risk Management Policy”. The policy is designed to meet the requirement specified in Division 2 Subdivision A 16 a. But it is limited to Commonwealth departments.

Commonwealth Risk Management Policy

To ensure the risk requirements are implemented effectively the policy specifies nine elements each department must implement. The elements are consistent with the elements in the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 31000:2018. The nine elements are:

- Establish a risk management policy.

- Establish a risk management framework.

- Define responsibility for managing risk.

- Embed systematic risk management into business process.

- Develop a positive risk culture.

- Communicate and consult about risk.

- Understand and manage shared risks.

- Maintain risk management capabilities.

- Review and continuously improve the management risk. (7)

To further the implementation process, the policy specifies components for each element. The components are essentially maturity or achievement levels. Element two – Establishing a risk management framework provides an example.

14.0 A risk management framework is the set of components and arrangements that provide the foundations and organization arrangement for designing, implementing, monitoring, reviewing and continually improving risk management throughout the entity.

14.1 An entity must establish a risk management framework which includes:

- an enterprise-wide risk management policy.

- an overview of the entity’s approach to managing risk.

- how the entity will report risks to both internal and external stakeholders.

- the attributes of the risk management culture that the entity seeks to develop, and the mechanisms employed in encourage this.

- an overview of the entity’s approach to embedding risk management into its existing business processes.

- how the entity contributes to managing any shared or cross jurisdictional risks.

- the approach for measuring risk management performance.

- how the risk management framework and entity risk profile will be periodically reviewed and improved.

14.2 The risk management framework must be endorsed by the entity’s accountableauthority. (8)

Section 14.1 lists the various components. The more components checked off, the higher the organization’s maturity level. This same maturity level approach is incorporated into an annual ERM self-assessment survey.

Comcover ERM Self-Assessment Survey

To reinforce ERM implementation, Comcover, a section of the Department of Finance, conducts a risk management self-assessment survey annually. The survey is essentially a risk maturity index which links with the requirements of the Commonwealth’s risk management policy. The linkage can be seen in the question and maturity index in the answer options.

Below is one of the questions from the annual Comcover benchmarking survey.

1.Question Objective: To determine whether your entity has a risk management policy and if so, is it documented, approved, and endorsed by your accountable authority.

Question Text: Does your entity have a risk management policy? Select all that apply.

- Your entity does not have a risk management policy.

- The risk management policy is drafted by awaiting senior management sign-off.

- The risk management policy is communicated to all staff to advise of any updates to the policy.

- The risk management policy aligns with relevant better practice standards.

- The risk management policy is reviewed and/or updated on an annual basis by senior management.

- The risk management policy communicated to all new staff upon commencement of employment.

- The risk management policy has been endorsed by your entity’s accountable authority. (9) (The 2021 Survey Questions have been changed. The Objective is the same. The question is: Which roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities for managing risk in your entity are formally defined and documented? The available responses are more focused and the list longer. They are drilling down to identify specific actors. For instance, Risk Champions, Dedicated risk function and Control and Treatment owners.) (10)

The benchmarking report has a six-level maturity model. The six levels are: fundamental (0-.99), developed (1-1.99), systematic (2-2.99), integrated (3-3.99), advanced (4-4.99) and optimal (5-6). The values in the parentheses are those associated with each level.

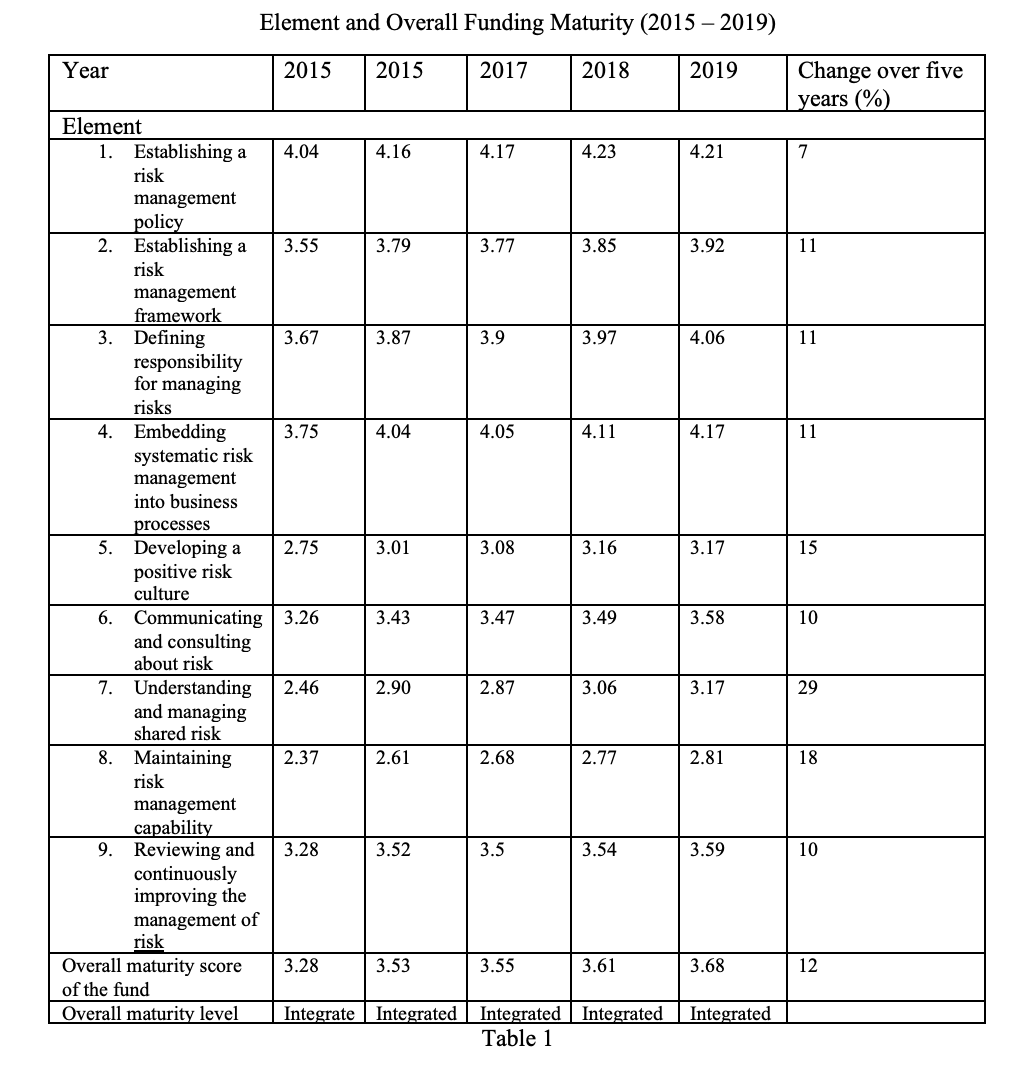

By conducting the survey annually, management can track ERM performance over time. Table 1 shows the results of the Comcover 2019 benchmarking report for 2015 to 2019. As can be seen, the results are aligned with the nine elements in the risk management policy.

The report indicates that the Commonwealth departments moved from a maturity score of 3.28 in 2015 to 3.68 in 2019. This is an indication that ERM is being taken seriously and being integrated into administrative practices.

While the Commonwealth’s Risk Management Guide can be seen as an ERM implementation model for all lower levels of government, it is not a mandated. State and local governments have the option of adopting ERM or not.

One of the states which has followed the Commonwealth model is New South Wales (NSW). It has not only adopted ERM, but it is mandating that local governments in the state adopt ERM. Another state, Tasmania, has taken a slightly different approach. Its primary risk management focus is environmental issues and project management. However, it does encourage local governments to implement ERM.

New South Wales

New South Wales is the most populace state in Australia. In 2019 it had a population of 8.13 million. In 2012 the NSW Department of Treasury issued “Risk Management toolkit for the New South Wales Public Sector”. The toolkit is designed to implement a New South Wales risk management policy issued in 2005. A core requirement of the 2005 policy states:

“Risk Management Standards – this covers the requirement to implement a risk management process that is appropriate to the needs of the department of statutory body and consistent with the current risk standard, i.e., AS/NZS 4360:2004 Risk Management.” (10) (AS/NZS 4360.2004 was incorporated into ISO 31000.Thus the Australian risk management standard is ISO 31000:2018.)

The policy further states. “To comply with the Policy, the department head or governing board of the statutory body must review existing arrangements for internal audit and risk management against the ‘core requirements’ and take steps to either establish relevant governance structures where these do not exist or align existing governance structures with the new requirements.” (11)

New South Wales Compliance Audit

In 2018, the NSW Auditor General conducted an ERM compliance audit of the Ministry of Health, the NSW Fair Trading function, the NSW Police Force, and the NSW Treasury to determine the degree of ERM implementation. The audit determined that all agencies are taking steps to strengthen ERM’s implementation. All had management policies and funded administrative activities to oversee ERM implementation. The audit determined that 65.5% of the employees reported that senior management communicated that managing risks effectively is a priority.

The audit did find several problems with implementation. For instance, it found that risks were being “managed in silos with little involvement of the central risk function.” (12) Thus, while ERM is well entrenched in NSW governmental operations, problems still exist after six years.

The NSW’s ERM approach is consistent with that of the Commonwealth. Both are based on ISO 31000. Both have voluntarily adopted ERM. Both see ERM as an important administrative tool, which can improve performance and manage costs. The NSW’s approach to spreading ERM to local government was initially encouragement as a best practice. This approach changed in 2019 when it mandated that local governments adopt ERM.

The next three sections outline the evolution to the ERM mandate.

Local Government Department Risk Guides Audit

In 2010, the NSW Division of Local Government issued Internal Audit Guidelines. The forward of the guideline states:

“Internal audit is an essential component of a good governance framework for all councils. At both a management and councilor level, councils must strive to ensure there is a risk management culture. Internal audit can assist in this regard.” (13)

The guideline goes on to state:

“The Division of Local Government’s Promoting Better Practice Program reviews have frequently made recommendation to actively encourage councils to undertake a comprehensive risk management plan across all functions of the council to proactively identify and management risk exposures.” (14)

The audit guidelines make several things clear. One is that the audit process is important to facilitating a good governance framework. The second is that the Division of Local Government is promoting ERM in the Better Practice Program. A 2012 “Promoting Better Practice Program Self-Assessment Check List” shows the linkage between the two.

Better Practice Self-Assessment Check List

The check list identifies the practices which are considered “Better Practice”. (15) The Governance Module has sections with questions related to ERM and audit practices. Under the Risk Management section four questions are listed. These questions are designed to facilitate the adoption of ERM. The four questions are:

- Does Council have a risk management plan that addresses all key business risks facing council?

- How was the risk management plan prepared?

- Has the council assigned responsibility across the organization for implementation of risk management plan?

- How does council monitor risk management plan and progress against risk management strategies?

Under the Internal Audit section one fundamental question is asked. “Does council have an internal audit program? Under this question are six subsets. One of these is: “Internal audit plan identified and examines key risks in risk management plan.”

The self-assessment check list is an attempt to encourage local governments to voluntarily adopt ERM. It also encourages local government to link the audit process with ERM.

This voluntary approach was changed in 2019, when the Division of Local Government mandated ERM. In the process of mandating ERM the Division strengthen the linkage between ERM and the annual audit.

New South Wales Local Government Mandate

In 2019, the Division of Local Government issued a discussion paper “A New Risk Management and Internal Audit Framework for Local Councils in NSW”. The framework lays out nine requirements and specifies actions local government must implement by 2026.

The nine requirements are.

- Appoint an independent Audit, Risk, and Improvement Committee.

- Establish a risk management framework consistent with the current Australian risk management standard.

- Establish an internal audit function mandated by an Internal Audit Charter.

- Appoint internal audit personnel and establish reporting lines.

- Develop an agreed internal audit work program.

- How to perform and report internal audits.

- Undertake ongoing monitoring and reporting.

- Establish a quality assurance and improvement program.

- Councils can establish shared internal audit agreements. (16)

Under each requirement is listed action steps each council is to take. Under Requirement 2: Establish a risk management framework consistent with current Australian risk management requirement is listed eight steps. These are:

- Each council (including county council/joint organization) is to establish a risk management framework that is consistent with current Australian standards for risk management.

- The governing body of the council is to ensure that the council is sufficiently resourced to implement an appropriate and effective risk management framework.

- Each council’s risk management framework is to include the implementation of a risk management policy, risk management plan and risk management process. This includes deciding council’s risk criteria and how risk that falls outside tolerance levels will be treated.

- Each council is to fully integrate its risk management framework within all of council’s decision-making, operational and integrated planning, and reporting processes.

- Each council is to formally assign responsibilities for risk management to the general manager, senior managers, and other council staff and to ensure accountability.

- Each council is to ensure its risk management framework is regularly monitored and reviewed.

- The Audit, Risk and Improvement Committee and the council’s internal audit function are to provide independent assurance of risk management activities.

- The general manager is to publish in council’s annual report and attestation certificate indicating whether the council has complied with the risk management requirements. (17)

The mandate requirements are like the steps outlined in the Commonwealth and NSW Risk Management Policies. The NSW mandate also places the responsibility for risk management with the Audit Committee.

New South Wales Statistical Assessment

Administrative documents tell one story. Given that these requirements are to be implemented by 2026, it is worth looking at the status of ERM’s use by NSW local councils. A review of 133 local governments in NSW indicates that 41 or 30.8% have an ERM policy. Of these 41, twenty-five or 58% have developed a framework or process. Thus, just 18.8% of local government in NSW have gone beyond a simple policy.

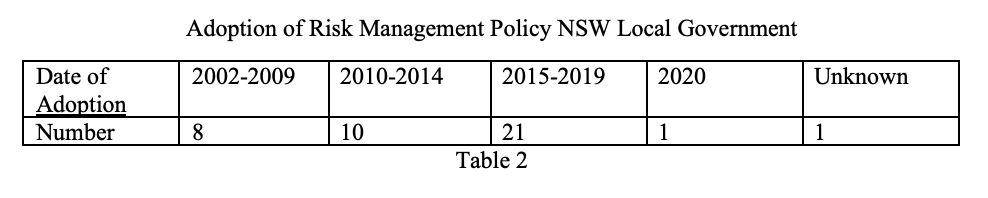

Table 2 shows the number of local governments with a Risk Management policy by the implementation date. As indicated, the earliest adoption of a risk management policy is 2002. The latest is 2020. Fifty-six percent of the local governments have adopted a risk management policy within the last five years. This indicates that while ERM is being adopted, it is a relatively recent occurrence.

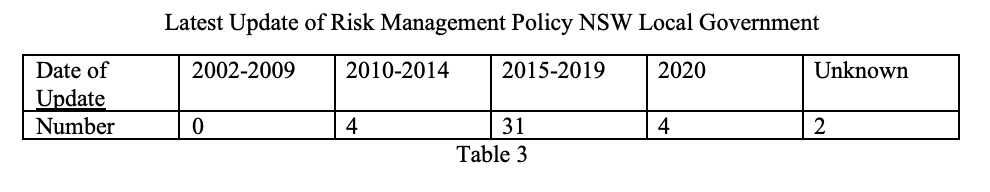

Table 3 shows the last year for the most recent policy update. As the table shows, 85.4% of these local governments have updated their policy within the last five years. Thus, ERM policies are being updated regularly. The Wagga Wagga City Council and the City of Willoughby exemplify the similarity in ERM policy and the continual policy updating.

Wagga Wagga City Council

The earlier adopters generally revise their Risk Management policy every two years. For instance, the Wagga Wagga City Council initially adopted the Risk Management policy in October 2002. It was last updated in February 2018. The policy states:

“Council recognizes that whilst risk is inherent in all its activities, the management of that risk is an integral part of good management practice and fully supports risk management as a central element of its Good Governance Framework. Therefore, all Wagga Wagga City Council departments and operations will adopt a risk management approach consistent with AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009 in their planning approval, review and control processes.” (18)

The risk management model used is ISO 31000. In the case of Wagga Wagga, the ISO 31000 model is revision 2009. However, as will be noted with the City of Willoughby below, the latest version ISO 31000:2018 will ultimately be adopted.

City of Willoughby

The city of Willoughby adopted its Risk Management Policy in June 2019. Under Policy Principles it is stated:

“Consistent with the Australian Standards, Organisation for Standardization 31000.2018, Risk Management – Guidelines (‘AS ISO 31000.21018’), these principles guide risk management practices in Council.

We will:

- Integrate risk management practices into all Council activities, including planning, decision making and project management process.

- Design and maintain a risk management framework that is structured, fit-for-purpose and dynamic.

- Consult with stakeholders and incorporate their perceptions, knowledge, and views.

- Make decisions about risk using the best available information, including historical and current data, experience, forecasts, and future expectations.

- Consider human and cultural factors.

- Continually improve the risk management framework, through learning and experience.” (19)

Both municipalities view ERM as an important part of their operation. Until 2019, the approach used to encourage local governments to adopt ERM in NSW was to emphasize best practice. This changed with the 2019 mandate. This mandate will force the remaining seventy percent of local governments to implement ERM.

Tasmania on the other hand, is an example of the continued use of local government voluntary compliance under a “Good Governance Guide”.

Tasmania

Tasmania is an island south of NSW. As of 2019, the population was 537,000. Tasmania does not list a risk management policy on its website. Under risk management there is indication that the focus of risk analysis using ISO 31000 is environmental. With respect to ERM, the Local Government Division in 2018 issued the “Good Governance Guide”. The guide was produced for local government elected officials. “It aims to help build a better understanding of, promote and enhance good governance in local government.” (20)

The guide includes ten elements. Five are listed below.

- Act with the highest ethical standards.

- Foster trusting and respectful relationships.

- Show a commitment to risk management.

- Make good decisions that promote the interests of the community.

- Commit to continuous improvement. (21)

Under the Robust Risk Management Section, it is stated:

“Risk is inherent in all aspects of a council’s activities. Risk management is therefore an integral part of good governance, good management practice and decision making in local government.” (22)

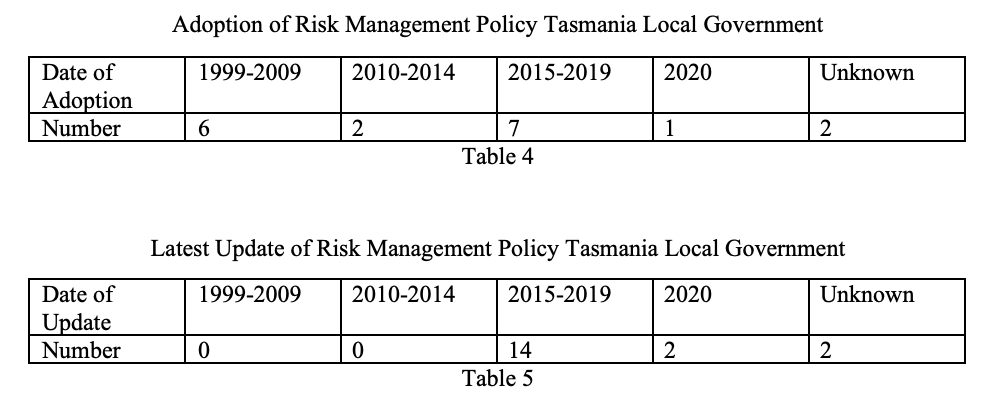

Of the 29 local government areas in Tasmania 17 or 58.6% have adopted a risk management policy. Table 4 shows the initial date of adoption. Table 5 shows the latest update. The earliest date of adoption is 1999. The latest is 2020. All but two, have updated their Risk Management Policy within the last five years. The remaining two do not provide dates on their policy. Thus, they are unknown for either adoption or update.

The Northern Midlands and Glamorgan Spring Bay Councils

The Northern Midlands Council implemented its risk management policy in 1999. The Glamorgan Spring Bay Council implemented its risk management policy in 2020. The revision process follows that of local governments in NSW. For instance, Northern Midlands Council revised their policy in 2000, 2005, 2008, 2013, 2016 with a review scheduled in 2020. Northern Midlands Risk Management Policy includes a performance review statement. It states:

“Council will ensure that there are ongoing reviews of its management system to endure its continued suitability and effectiveness in satisfying the requirements of AS/NS ISO31000):2009 Risk Management- Principles and Guidelines. Records of all reviews and changes shall be documented for future reference.” (23)

The Northern Midlands Council also “recognizes that risk management is an essential tool for sound strategic and financial planning and the ongoing physical operations of the organization.” (24) Similarly, the Glamorgan Spring Bay’s vision “is to have a mature risk management framework which is embedded in the organisation’s culture, enabling risk management principles and practices to be seamless in all planning, decision making and operations” (25)

There can be no doubt that local governments in NSW and Tasmania have voluntarily adopted ERM. They have linked the risk management format with ISO 31000. The difference is that NSW in 2019 mandated local governments adopt ERM. The mandate will further ERM implementation in NSW.

Given the mandate, a question is: Does Tasmania need to mandate that local government adopt ERM for it to spread? A review of the 17 local government areas which have adopted a risk management policy, indicates that 14 or 82.4% have an implementation framework. The framework is generally consistent with ISO 31000. This would indicate that a sophisticated ERM process is being voluntarily adopted.

Conclusion

In Australia, ERM is viewed as an important part of government activities. It is being implemented by governments at all levels. Moreover, there is considerable consistency in the ERM approach used. That approach is ISO 31000. Further, the application of ISO 31000 is well intrenched in the Commonwealth federal and NSW state government administrative agencies. At the local level, 58% in NSW have an ERM framework. In Tasmania, 82.4% of the local government areas also have an ERM framework. This is important because the framework tells management and employees what is expected of them. It also ensures that the ERM process implemented is consistent with ISO 31000.

Despite being well imbedded in Australian governments, the statistics indicate that there are some issues. In NSW only 41 or 30.8% of the 132 local governments have implemented ERM. Of these, 25 or 58% have an ERM framework. This low level of solid ERM implementation may be one reason the state of NSW is mandating ERM. It is obvious NSW believes the mandate will compel local governments to integrate ERM more completely into their administrative activities. Tasmania, on the other hand, has decided to continue to encourage ERM’s adoption.

Taking a step back and looking at the overall picture, there are eight policy implications. First, it is helpful if all governments are using the same ERM model. This provides consistency and the ability to translate the solutions to problems from one government to another.

The second is that the more detailed the ERM framework, the more likely that implementation will occur in a uniform manner.

Third, ERM is seen as part of good governance practice. This idea is being used successfully to encourage its adoption.

Fourth, an annual self-assessment survey using a maturity model, can provide agency mangers with comparative information. The annual assessment also keeps ERM implementation as part of management’s thought process.

Fifth, ERM compliance audits provide additional assessment on ERM implementation. It also ensures that self-reporting results are objectively assessed.

Six, the use of good governance practice while successful in ERM adoption, may not result in uniform implementation or widespread adoption. Consequently, a mandate may be useful. This is consistent with the Finish conclusions.

Seventh, to fully implement ERM and obtain a broad agency base maturity level, will take time. Even after five years, the Commonwealth and NSW still have agencies which have not reach full ERM maturity.

Eight, the Commonwealth of Australia and the states of NSW and Tasmania provide examples of the how ERM can be effectively implemented in government.

An issue which needs to be highlighted is that while initially NSW and Tasmania were using similar approaches for encouraging ERM’s adoption, the NSW’s mandate crates a divergent path from the voluntary approach. As a result, the adoption of ERM in NSW local government will likely increase. Tasmania’s encouragement of ERM’s adoption as an integral part of good governance will continue the voluntary approach. The fact that both approaches are being used, will provide national and state governments interested in having local governments implement ERM the opportunity to evaluate which is the most appropriate for their circumstances. The use of a voluntary approach versus a mandate can also be instructive to the private sector.

Endnote

Note: Some of the urls below do not link properly to the document. However, by entering the title of the document, it appears. It also seems that the Comcover 2018 self-assessment survey questionnaire is no longer available online. However, the 2021 questions are available as noted below. Finance Department. If not available from them, I have a copy which I will provide.

- Kline, James J. and Greg Hutchins, (2017). Enterprise Risk Management: A Global Focus on Standardization. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, Volume 36, Number 6, page 44-53.

- Sheiner, Louise and Sophia Campbell, 2020, “How Much Is COVID-19 Hurting State and Local Revenues?”, September 24, Brookings Institute, Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/09/24/how-much-is-covid-19-hurting-state-and -local-revenues/

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021, Enterprise Risk Management Maturity Model, February 4, Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications and products/enterprise-risk-management-maturity-model.pdf.

- ASQ/ANSI GI, 2021, “Guidelines for evaluating the equality of government operations and services”, Quality Press, Milwaukee WI 53203-2914.

- Oulasvirta, Lasse and Ari-Veikko Anttiroiko, (2017). Adoption of Comprehensive Risk Management in Local Government. Local Government Studies, Volume 3, pp. 451-474.

- Commonwealth of Australia, (2013). Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, No. 123, 2013, page 18. Retrieve from https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2013A00123

- Australian Government Department of Finance, (2014). July 1, page 9-10. Commonwealth Risk Management Policy, Retrieved from https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-11/commonwealth-risk-management-policy-o.pdf

- Ibid page13.

- Australian Government Department of Finance, 2018 “Comcover Risk Management Benchmarking Program 2018: Survey Questions”, Comcover, Department of Finance, One Canberra Avenue, Forrest Act 2603, Australia, Retrieved from: https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/documents/survey-questions-2018%20comover%20bnchmark%program.pdf

- Australian Government Department of Finance, 2021, “2021 Comcover Risk Management Benchmarking Program: Survey Questions”, Comcover, Department of Finance, One Canberra Avenue, Forrest Act 2603, Australia, Retrieved from: https://www.finance.gov.au/sies/default/files/2021-02/2021%20Comcover%Risk%20Management%20Benchmarking%20Questions.pdf

- New South Wales, (2012). NSW Treasury Risk Management Toolkit for NSW Public Sector Agencies. Retrieved from nswtreasury prod.acquia-sites.com/sites/default/files/pdf/TTP12-03a-Risk-Management-toolkit-for_the_New_South_Wales_Public_sector.

- New South Wales Treasury, (2009). Internal Audit and Risk Management Policy for the NSW Public Sector, Office of Financial Management: Policy & Guidelines Paper,TPP 09-05, page 1. Retrieved from https://arp.nsw.gov.au/assets/ars/8a049/tpp09-5_dnd.pdf Official internet site, http://www.treasury.new.gov.au/

- Ibid, page 6.

- New South Wales Auditor-General, (2018). Managing risks in the NSW public sector: risk culture and capability. April 23 page 8. Retrieved from https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/our-work/reports/managing_risks_in_the_NSW-public-sector-risk-culture-and-capability

- New South Wales Division of Local Government, (2010) Internal Audit Guideline, September, page 5. Retrieved from https://www.olg.nsw.gov.au/wp-cotent/upload/Internal-Audit-Guidelines-September-2010/pdf

- Ibid page 33.

- New South Wales Division of Local Government. (2012). Promoting Better Practice Progress Self-Assessment Check List. Retrieved from https://www.olg.nsw.gov.au/councils.governance/promoting-better-bractice/promoting-better-practice-review-reports/?Selected, 2012 Promoting Better Practice Self-Assessment Check List.

- New South Wales Division of Local Government. (2019). A New Risk Management And Internal Audit Framework for local councils in NSW: Discussion paper, page 4. Retrieved from https://www..olg.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/A-new-risk-management-and-intrnal-audit-framework-for-local-councils-in-NSW

- Ibid page 23.

- Wagga Wagga City Council. (2002). Risk Management Policy, Policy 079, page 2. Retrieved from https://wagga.nsw.gov.au/_data/assets/pdf.file/008/2222/Risk-Management-Policy-POL-079.pdf

- Willoughby City Council. (2019). Risk Management Policy. June 24, page 2. Retrieved from https://www.willoughby.nsw.gov.au/council/policies/policies-Publications/Risk-Management-Policy

- Local Government Division of Tasmania. (2018). Good Governance Guide. Page 7. Retried from dpac.tas.gov.au/-data/assets/pdf-file/0006/380427/Good-Governance-Guide-June-2018.pdf

- Ibid page 8.

- Ibid page 50.

- Northern Midlands Council. (2020). Policy Manual Risk Management, page 3. Retrieved from https://www.northernmidlands.tas.gov.au/sourve-assets/images/Risk-Management.pdf

- Ibid page 5.

- Glamorgan Spring Bay, (2020). Glamorgan Spring Bay Risk Management Policy 3.15. Retrieved from httsp://gsbc.tas.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/3.15-Risk-Management-Policy.pdf.

Appendix A Methodology

The data is based on a review of the local government’s website. The determination of whether a local government has a risk management policy was determined by review of three key words in the search bar. These were risk management policy, policies, and Enterprise Risk Management. The NSW and Tasmania list of local governments examined came from Wikipedia. The 133 NSW local governments used are four more than Wikipedia’s list which was accurate as of 2016. Because of this disparity it is difficult to determine the exact percentage of local governments covered. A guess is that the 133 cover at least 85-90% of the NSW local governments. The 29 local governments area in Tasmania cover all the cities and towns. In many cases they are the administrative councils for those cities and towns. Regardless of direct administrative activity, the 29 represent models for the cities and towns.

Bio:

James J. Kline has a PhD in Urban Studies. He is a Senior Member of ASQ, a Six Sigma Green Belt, a Manager of Quality/Organizational Excellence, and a Certified Enterprise Risk Manager. He has work for federal, state, and local government. He has over ten year’s supervisory and managerial experience in both the public and private sector. He has consulted on economic, quality and workforce development issues for state and local governments. He has authored numerous articles on quality in government and risk analysis. His book “Enterprise Risk Management in Government: Implementing ISO 31000:2018” is available on Amazon. He is the principle of JK Consulting. jeffreyk12011@live.com

This article examines the Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) administrative and philosophical approach taken by two Australian states. The states are New South Wales and Tasmania. While both have stressed that ERM is part of good governance, New South Wales has moved from a voluntary approach, used by both, to ERM’s adoption to a mandate. The mandate is consistent with the risk maturity level approach taken by the Commonwealth of Australia. All three ERM approaches are based on ISO 31000.