he Safety culture is rightly a preoccupation for health and safety professionals. It’s not a luxury; it’s not even a choice. Every organization has a safety culture, but not all ensure the workforce is adequately protected. The holy grail of a strong safety culture allows those managing an organization’s duty of care to employees the chance to oversee a system in which everyone takes responsibility for their own health and safety and each other’s.

he Safety culture is rightly a preoccupation for health and safety professionals. It’s not a luxury; it’s not even a choice. Every organization has a safety culture, but not all ensure the workforce is adequately protected. The holy grail of a strong safety culture allows those managing an organization’s duty of care to employees the chance to oversee a system in which everyone takes responsibility for their own health and safety and each other’s.

In that ideal state, the health and safety practitioner become a business partner, offering specialized advice where it’s needed and monitoring innovations in risk assessment and control that might benefit the organization.

Few safety managers work in businesses that have achieved this safety culture nirvana; most are still on the path, working to improve employees’ and managers’ consciousness of risk, and build their willingness to share its management. This paper is aimed at that majority and suggests three priorities to focus on to build a positive culture.

Major influencers

No one person can build an organization culture on their own. But some people are inevitably more influential than others. If people look to you as the occupational health and safety specialist, then they are more likely to take a steer from you on safety culture than from, say, the head of accounts.

The old saying in sales that “people buy from people” runs true for most other things. People believe people they trust and respect and, most of all, people who talk their language. How you talk (and sell) to people is a vital part of your impact on safety culture.

EHS professionals have a singular reach inside organizations; they can “access all areas” from the C suite to the shopfloor and the layers of management in between. But that privilege brings its own challenges. It means having to learn the language that resonates with each of those different groups. And that, in turn, means trying to understand what motivates them.

Adjust your EQ.

That ability to imagine yourself in someone else’s shoes and to see things through their eyes, is one of the main components of emotional intelligence, also known as EQ. It is one of the most valuable, attributes a business leader can have. If you can achieve that perspective, whether you are dealing with executives, middle managers, or frontline operatives, then you are more likely to shape your messages to suit that group and to carry them with you.

One thing that is unlikely to engage people at any level of the organization is the language of regulation. Telling people, they must do things because “the law says so” may earn you compliance in the short term, but it’s no way to build a culture in which safety is an organizational value, and where everybody sees themselves as playing an important part in keeping themselves and their colleagues safe.

After completing the annual 5 Star Health & Safety Management System™ Audit, I make a point of talking about the companies HS&E culture and demonstrate how the culture has improved.

Key indicators

Knowing what motivates people at work often involves understanding what they are evaluated on by their managers. The safety director at an airport once explained to me that he and his peers on the board were all tasked by their CEO with “creating excellent passenger journeys”. This KPI shaped his fellow directors’ discussions – people usually manage what they are measured on.

When the safety head was seeking support to improve housekeeping standards at the terminal, he didn’t talk about the potential liabilities under the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992. Instead, he painted a picture of the impact on travelers starting their dream holiday or an important business trip, having to skirt a cordoned-off areas on the concourse where someone was being attended by paramedics because they had slipped on an unmapped spill and hurt their back.

Convincing operatives and supervisors to take safety seriously involves showing them you understand the other pressures they are under – such as production deadlines – and working with them to find safe systems that don’t slow them down unnecessarily. It may also be about making worker safety personal to them, giving real-life examples of people who have had accidents or developed long-term health conditions doing similar jobs, and the impact it has had on their lives. It is a positive message to show that good occupational health and safety isn’t an abstract aim and that it’s about the organization wanting everyone to thrive and go home in the same condition they came to work because they are valued.

If you can convey those messages, tailored to fit the different constituencies in your organization and couched in language they recognize, you will be on the path to developing an evolved safety culture. If you can persuade others with influence in the organization to do the same, you will traverse that path a whole lot faster.

Walking the talk

If talking to people in terms they understand and that resonate with them is important, even more so is showing them by your actions that you mean what you say. Especially if you are one of those setting the direction of an organization.

The progressive “death of deference” triggered by social changes in the second half of the 20th century put an end to the perception that those in leadership positions were superior to those they lead. The social stratification, summed up in phrases such as “knowing your place” and the warning not to get “ideas above your station”, dissolved. The class system that replaced it was once described by futurist Peter Cochrane as a simple division between those who spend money to save time and those who spend time to save money. The reality may be a little more complicated, but the important distinctions are certainly economic.

This new class system is true of business too. Anyone working at operational level knows that a manager is paid more than them and that an exec is paid a lot more. But they don’t inhabit separate universes; the days of the executive washroom – and in many businesses, the corner office – are past.

Tone at the top

Those at the top of businesses don’t operate according to a completely different set of rules. That means that in building or maintaining a strong safety culture, senior staff must be seen to be modelling the behavior they ask of everyone else.

The trope of senior managers failing to wear safety helmets on visits to construction sites is a well-worn one – old hat, you could say, but the point it encapsulates is important. If managers don’t wear PPE, or stay on pedestrian routes in depots, everyone who is there to see will take their cues from that, whatever they have been told. “Do as I say, not as I do,” is a direction that doesn’t even work with children – with adults it’s disrespectful and counterproductive.

Similarly, there is no value in starting meetings with a mandatory “safety moment” if it’s clearly treated as a distraction, something to be got out of the way before the important matters. Even when they begin well, it’s easy for these practices to become stale in time. It’s the safety practitioner’s job to find ways to make them fresh and stimulating.

Keeping leaders committed to their roles in building safety culture, in walking the walk sometimes literally, in turning up for site safety tours and having proper conversations with local staff about their work and the risks involved – is a sales job. It involves selling them on the idea that safety is not a priority, subject to shifting levels of attention, but a value, fundamental to the working of any business a leader manages.

Of course, the best way to get that message through the department heads is by convincing their bosses, since that’s who they take their biggest cue from. That may be a tough ask for a safety professional, but this is why the safety and health membership bodies put so much weight on the need to develop influencing skills as well as keeping on top of the technical parts of the job. But it’s a tougher ask to develop and maintain a strong safety culture without tone at the top.

“safety is not a priority, subject to shifting levels of attention, but a value, fundamental to the working of any business a leader manages. ” Louis Westermann

Firm foundations

When I’m talking to people about the dangers of misplaced safety and health and interventions, I often use the analogy of trying to put cherries on a rotten cake. It’s not a pleasant image but it’s intended to highlight the futility of, as an example, organizations spending effort promoting general employee health and wellbeing, when their controls to stop the same employees from exposure to excessive physical or mental stress, are patchy at best. You cannot build securely on weak foundations. It’s true for occupational health and it’s equally true for safety culture.

We have already looked at how important it is to use the right language to influence OSH culture and how leaders must be seen to “walk the talk”, following the standards they set the rest of the workforce.

Mundane as it may sound, the foundation stone of safety culture is consistently providing the controls to keep people healthy and safe. From the top of the hierarchy down, stopping or reconfiguring hazardous processes, educating people to deal with the hazards you can’t design out, supervising them where necessary, and finally providing sound protective gear, procured to a standard rather than just a price.

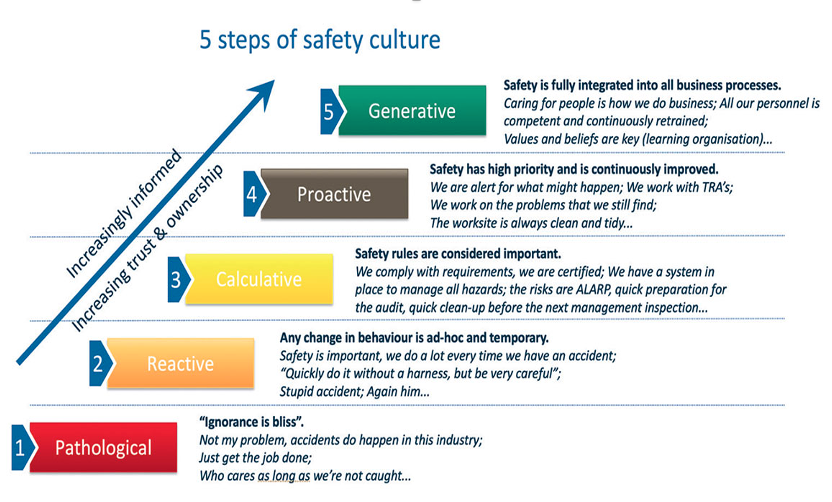

Compliance plus

If this sounds very much like what any employer is supposed to do to meet their statutory obligations, that’s because it is. But that quality and consistency of what safety law calls “arrangements” and the United States and Canada calls “standards” to stop people being hurt is also necessary to build a strong safety culture; If this sounds very much like what any employer is supposed to do to meet their statutory obligations, that’s because it is. But that quality and consistency of what safety law calls “arrangements” and the United States and Canada calls “standards” to stop people being hurt is also necessary to build a strong safety culture; necessary but not sufficient. Equipping people to work safely is not enough to propel your organization down the Bradley curve or up the safety ladder to the point where employees are actively looking out for their own and each other’s safety and welfare. But if you don’t do it all, the other effort is probably a waste of time, like covering a moldy cake with glacé cherries.

Although using the right language, or senior management wearing the right PPE, are important, they weigh lightly against the message people get from the basic provision of training and equipment. There is even an argument that this foundational provision of safe working conditions is the main driver of the safe behavior and attitudes that are key to a strong safety culture.

My good friend Dr Dominic Cooper has researched safety culture for more than 20 years – more than half the time the concept has been around – and written and lectured widely on the subject. In his book Improving Safety Culture, a Practical Guide (BSMS 2001), Dr Cooper breaks down safety culture into three components:

Situational aspects – the physical environment and organizational policies and controls to manage safety.

Psychological aspects – how employees feel and think about safety.

Behavioral aspects – what employees do (or don’t do) to maintain and improve safety.

The elements all influence each other, but Cooper argues that the main lever any organization can use to change safety culture is to improve the situational aspects. Thorough managerial commitment to optimize safety, with adequate funding and other resources, is the biggest influence on an individual’s actions, he argues.

And the practice of safe behavior – when employees perceive it as a work requirement because of all the attention and resourcing it receives – means that the psychological aspect naturally follows. Cooper says that when people change their behavior, over time they automatically change their attitudes and beliefs. So arguably the most critical thing safety professionals can do, both for workforce safety and for safety culture, is to make sure those basic protections are consistently applied across the organization.

Of course, to do so, they need a reliable flow of data on numbers trained and training effectiveness, corrective actions closed out and all those other inputs that are often described as leading indicators.

Sadly, in many organizations with highly evolved systems for inventory control or HR management have OSH managers still relying on basic spreadsheets. That’s not sufficient to monitor the temperature of OSH provision in an organization. Good data flows are essential to the checking component in the plan-do-check-act model that forms the template for safety programs – and for many other business processes.

There are plenty of building blocks for a good safety system and a strong safety culture but basic provision of safe systems, and the information to check that provision are the ones to lay first.

Conclusion

Organizations are made of people and people behave differently in different combinations and environments. As a result, safety culture management is always contextual and the directions in this paper have necessarily been broad to allow for those variations in context. But because organizations are all made of people, there are common patterns in their cultural development, whether the activity is retail or road mending.

So, if you concentrate on setting in place the building blocks of providing appropriate protection, using suitable language for safety messages, and encouraging leaders to set the right example, you should succeed in strengthening your safety culture.

Bio:

Dr. Bill Pomfret of Safety Projects International Inc who has a training platform, said, “It’s important to clarify that deskless workers aren’t after any old training. Summoning teams to a white-walled room to digest endless slides no longer cuts it. Mobile learning is quickly becoming the most accessible way to get training out to those in the field or working remotely. For training to be a successful retention and recruitment tool, it needs to be an experience learner will enjoy and be in sync with today’s digital habits.”