In part one we saw that China has made great strides in terms of product quality, notably in the tech sector. But it still has a long way to go in other products. Driven by the growing middle class, who like all middle class buyers want value for their money, and by the Chinese government’s desire to improve the tarnished “made in China” brand, there is a strong interest in improving product quality.

In part one we saw that China has made great strides in terms of product quality, notably in the tech sector. But it still has a long way to go in other products. Driven by the growing middle class, who like all middle class buyers want value for their money, and by the Chinese government’s desire to improve the tarnished “made in China” brand, there is a strong interest in improving product quality.

According to Xinhua, the official press agency of the Chinese government, “With an insufficient supply of high-end products and services, great efforts will be required to improve quality, according to the plan released by the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council. The focus of the plan is on improving the quality of services and products, especially farm produce, food, medicine, consumer goods, and equipment.”

And a research report released at the 14th Conference on the Latest Trends of Sustainable Development in Beijing on April 18, 2018 (“Stage Report on the Development of China Corporate Sustainability Index”), shows that the majority of companies in the research emphasized the importance of high-quality products and services in their publicly released information, and about half have introduced specific measures to improve quality, such as applying more rigorous quality management systems and strengthening staff training.

And a research report released at the 14th Conference on the Latest Trends of Sustainable Development in Beijing on April 18, 2018 (“Stage Report on the Development of China Corporate Sustainability Index”), shows that the majority of companies in the research emphasized the importance of high-quality products and services in their publicly released information, and about half have introduced specific measures to improve quality, such as applying more rigorous quality management systems and strengthening staff training.

According to our contacts, China doesn’t have a quality strategy per se, not like Japan did, if we want to draw that comparison. There is no Chinese equivalent of W. Edwards Deming, Joseph Juran, Eiji Toyoda, Kaoru Ishikawa, or Taiichi Ohno. But maybe there doesn’t need to be. It isn’t as if Chinese companies are going to have to bootstrap their quality initiatives. The Chinese have already been exposed to and implemented concepts like lean or the Toyota Production System. Ohno visited the First Automotive Works (now FAW) in China back in the 1970s and 1980s, and outside firms continue to work with Chinese companies to implement modern quality strategies.

“The large firms have learned from the Japanese; they know about the Toyota Production System or have trained under the system when working at Japanese joint ventures,” says Stanley Chao author of Selling to China (iUniverse, 2012). “I’ve witnessed Chinese manufacturers having daily meetings to discuss these holistic quality methods, where along the line can they improve, what to add to prevent failures, etc. Big companies see the pros of preventing failures and shutdowns.”

Renaud Anjoran, general manager of Sofeast, a quality assurance and engineering firm based in China, agrees. “There are obviously some China-based factories, including some fully Chinese-owned, that do [implement advanced quality techniques]. From my observations, it always comes from foreign influence—generally, large customers’ requirements. Unfortunately, this is a tiny, tiny fraction of all manufacturers in China—well below 1 percent.”

Made in China 2025

Although the biggest drivers for implementing a more process-oriented approach in Chinese manufacturing may well be the influence of foreign manufacturers bringing in these techniques, and the need for manufacturers to implement these techniques if they want to succeed, the weight of the Chinese government itself can’t hurt.

The latter can be seen in China’s “Made in China 2025” initiative, which does have a quality component, although it’s difficult to learn much about it. (You can read a synopsis of “Made in China 2025” in Laurel Thoennes’ article, “Made in China 2025.”) According to the Chinese government website, China wants to improve consumer goods quality by, among other things, adopting a wider range of global standards during the next five years. According to the new guideline, more than 95 percent of consumer goods in major sectors will meet international standards by 2020.

In 2016 Premier Li Keqiang mandated that “government departments should enhance coordination, while enterprises need to have stronger emphasis on quality, branding, R&D, and marketing. They also need to create mass awareness on branding.” Regarding new guidelines on improving consumer goods standards and quality, which were initiated by the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection, and Quarantine (AQSIQ), Li also stated the importance that the quality of consumer goods made in China “withstand the test of the market.”

A more forceful declaration was reported by Xinhua: “The government will intensify quality control, strengthen control of intellectual property right infringements as well as the manufacturing and selling of fake and shoddy goods.”

The mention of intellectual property rights and shoddy goods sounds like it was most likely written for Western ears. When asked if all this talk of improving quality and addressing intellectual property rights was just window dressing, Dan Harris, an attorney with Harris Bricken and a leading authority on legal matters related to doing business in China, tells us that he has no doubt that the Chinese government is serious about this effort. However, “I have my doubts as to whether (and even how) government desires and exhortations will translate into better quality from China’s factories, especially for foreign buyers,” says Harris.

While not doubting that China wants to improve its brand, Anjoran doesn’t believe Made In China 2025 is addressing quality. Rather, it seems to rely on automation itself as a means to address quality rather than a quality-by-design or quality process approach.

“Let’s say it clearly: Quality is not a central theme in Made in China 2025,” says Anjoran. “It is seen as a logical consequence of automated processes.”

And certainly, while automation contributes to consistency, and artificial intelligence (AI) can enhance that consistency, what’s missing is attention to the human element. What’s lacking are skilled equipment maintenance specialists (e.g., electricians, control specialists, mechanics), says Anjoran, and there seems to be no progress on this front. “Chinese manufacturers are encouraged to invest in automated equipment, not to train the people who will ensure this equipment will keep running as expected and make good products.”

Chao agrees, adding that the goal of Made in China 2025 is self-sufficiency, and to get away from buying foreign products and components, particularly in high-tech, robotics, AI, pharma, and the internet.

“The real point of Made in China is for China to move up the food chain,” says Chao. “For example, rather than just supplying the chemicals for pharma products, China wants to make the actual medicines.”

The importance of this goal can be seen in the very recent near collapse of Chinese telecommunications giant, ZTE. The United States banned the sale of U.S.-made parts to the company for a period of seven years because of ZTE actions stemming from conspiring to sell U.S. technology to Iran and North Korea. And with all its eggs in the United States’ basket, the ban left the company high and dry and faced with laying off nearly 80,000 employees.

Putting aside the illegality of ZTE’s actions that spawned the ban, when a Chinese company depends on U.S. parts to keep it afloat, it has to question whether it shouldn’t be making those parts domestically. And if it is going to do that, then the quality of those parts must be on par with what it is getting from the United States. Supply chain math is the same no matter where you are. It all boils down to balancing price, performance, and risk.

As an aside, if ZTE and other Chinese manufacturers increasingly turn to Chinese producers to provide tech products, where does that leave U.S. companies that source to China? You can hear in their own words what some small-business owners have to say about that in Ryan Day’s article “Sino-U.S. Trade: Truth From the Shop Floor.”

Shifting quality

In some cases, the issue of addressing quality is simply sidestepped. One interesting side effect of China’s middle-class boom and rising wages is that the production of mass-produced, often low-quality products is slowly moving to other countries. “With wages in China rising an average of 13.3 percent from 2000 to 2013, many of our customers and others have relocated manufacturing to lower-cost developing countries, namely India and Vietnam,” says John Niggl, client manager at InTouch Manufacturing Services, an American-owned company that provides product inspection and related quality control services for overseas manufacturers. “Products which are relatively labor intensive to manufacture, such as garments, have been among the first to leave China. And products that require more sophisticated quality control and production processes have gradually taken their place.”

In a sense this has shifted the quality equation. If the overall quality of Chinese products was brought down by certain product categories, and production of those products moves from China to other countries, the result is an overall improvement in quality for China.

How to work with suppliers

The answer to the question, “Has Chinese product quality improved?” is yes. Quality has improved in certain sectors: high-tech, garments, and some luxury items. Quality has remained the same in others, and in some cases the “quality problem” has simply left the country. Technologically, the country is growing by leaps and bounds, and more of its urban citizens are being raised from poverty and joining the middle and upper-middle class. As its citizens now demand quality from their own producers and the government is increasingly being pressured by market forces to improve its brand, the idea of quality no longer seems to be an abstract, luxurious attribute but a must-have in today’s market.

But many, some would say most, of China’s manufacturers still have a long way to go to improve their quality. Although the expertise and technology exists to do that, there are still too many small manufacturers willing to cut corners on materials and processes to maximize profit, say our consultants.

This means that companies doing business in China still need to be careful about working with Chinese suppliers, at least initially. Working with smaller Chinese manufacturers is different than working with Western manufacturers. In the West we are comfortable with doing an initial on-site survey of a contract manufacturer, then a first-article inspection of the contracted product, and then trusting the contractor to do the right thing. Maybe we do some random site visits to make ourselves more comfortable. And of course, if the manufacturer breaks the law or the contract, we can always take legal action.

This relatively hands-off approach doesn’t work with many Chinese suppliers, say our consultants. At least initially, more time must be spent vetting, laying out specifics, agreeing on protections, and intensely overseeing the manufacturing process, the raw materials, and in some cases the contract manufacturer’s supply chain.

With that in mind the consultants in this story have made some common-sense recommendations on how to handle relations with Chinese manufacturers.

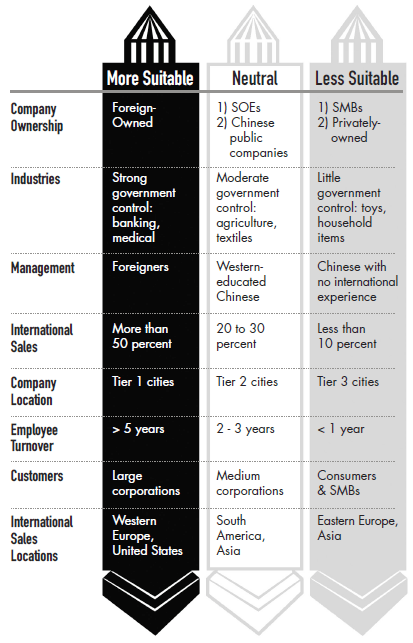

Figure 1: Selecting companies as partners. Source: Stanley Chao |

Stanley Chao, author of Selling to China

• Know that a contract is basically unenforceable in China. In short, the Chinese know you don’t have much recourse so are not afraid of any of the “punishments” implemented. Once you know this, it allows you to find other ways to protect yourself.

• Find alternative ways to protect yourself by implementing self-enforcing procedures: Hire your own staff to do work-in-progress quality checking, do sub-supplier audits, do your own sample testing before final shipments, and inspect invoices and purchase orders from their sub-suppliers. Better yet, place the orders yourself for your supplier. These measures should also be added to the contract. In short, take trust out of the equation.

• Hire a Chinese specialist to handle your China suppliers, someone who has experience in China; can read, speak and write Chinese; has experience with your specific industry or product; is able to “read” your supplier—i.e., who is he, where did he come from (the Mao Generation concepts I write about in my book); and can spend time in China getting to know your supplier intimately.

• Look for long-term solutions. Find a partner, not just a supplier, that you want to work with for years. If you look for short-term and cheaper answers, you’ll get shoddy, cheap product. Find this partner, make an investment in the partner, and show an interest to want to make that partner a better manufacturer. In return, you’ll get a reliable and dedicated partner.

• Lastly, take the time to explain to your Chinese supplier why you want things done in a certain way. Because of generational gaps, cultural differences, and language barriers, the Chinese often simply don’t know why you want things done a certain way and so look for shortcuts not knowing the ramifications of what they are doing.

Renaud Anjoran, general manager of Sofeast

For those buyers of OEM/ODM products that are not very different from what the manufacturer is already making, I would suggest:

• Identify and screen manufacturers that are a good fit for you (not too small or too large, not selling on markets widely different from yours)

• Qualify the manufacturer (do a background check, audit their quality system and their processes)

• Do all the work of defining your expectations, and make sure the people in the factory understand and confirm them. One common source of failure is the buyer has a relatively high standard but works with a factory that sells to buyers with a lower standard.

• Inspect and give feedback. Check quality early in production, at least for the first batch, and keep inspecting at least the first five batches

• Visit the factory regularly, ideally every two to three months. Get to know the key people, and keep them motivated to work with you. Look for changes between two visits.

Paul Midler, author of Poorly Made in China

• Do not accept everything at face value. The manufacturer may present a facade, and it’s important to find out what is taking place behind that facade.

• Vigilance. Factory owners will wait for the customer to become complacent before making certain moves.

• If the contract-manufacturer itself has raw-material suppliers, they may switch suppliers to cut corners, adversely affecting your product. They may not tell you when they do this. In some instances, it’s the sub-supplier that has done this without the supplier’s knowledge, and so when things go wrong, the manufacturer is truly innocent. But in most cases, because factory owners are incredibly savvy, they know all of the tricks and are fully aware of what they have delivered, even if the producer insists it was itself caught by surprise at a product failure.

• The supplier may learn of a method for reducing costs and will employ it, even if it increases product risk.

Although he has seen some change, Midler still believes there are shop owners who say they will do one thing but then do something else, and factory bosses who believe that what the customer (and the end consumer) don’t know won’t hurt him. However, Midler recently told us that the stories we read about in the news are are typically worst case scenarios. And that the reality is that many Chinese manufacturers still struggle to make a quality product, sold at a reasonable cost, and delivered within an acceptable time frame.

Mark Tanner, director of China Skinny

• Have a trusted person on the ground.

• If not from your business, ensure you have trusted partners in China to oversee QC and regularly visit.

• Trademark and copyright all intellectual property (IP). There are increasingly cases where the good guys are winning those cases in court. China is doing so much to grow its own IP that there is also self-interest in enforcing it. It won’t work every time, but better to have some protections than nothing.

• Regularly monitor common sales channels for your goods—e.g., e-commerce— and potentially, work with e-commerce platforms if relevant

• Have strong key performance indicators and service-level agreements in place with material disincentives to not meet them—and act fast and firm when they aren’t met.

“Whilst I think there are some enormous opportunities for U.S. manufacturers in China, they should be very careful about jumping into joint ventures and other deals requiring them to give away IP,” says Tanner. “There are success stories, but there are also countless examples where it didn’t turn out well. I would suggest they speak to an experienced advisor on the matter and read Chinese war strategies before making any decisions.”

Conclusion

There is no doubt that China has rapidly improved the quality of it’s products across key sectors, including some we didn’t even touch on here. (Chinese automakers have made gigantic strides, for example.) Much of the poor quality of the past can be seen as rooted in growth that far outpaced capability, as well as in the cultural vestiges of the Mao Generation, as Chao puts it. As younger, more affluent, and more world-savvy consumers enter the Chinese market and workforce, the faster quality improvements will accelerate.

Middle-class buying habits, coupled with Premier Li’s quality mandate and the need to improve China’s brand image will see China quickly meet or exceed consumers’ quality expectations worldwide. This is already happening in the tech sector and moving quickly into luxury items. And while mass-produced, low-end and low-quality products still abound, look for China to continue to outsource those items and instead focus on the higher quality and higher-priced products that its domestic market demands.

If China can please the largest retail market in the world—its own—“Made in China” will take on a completely different meaning, going from being scary bad, to scary good.

(C) Quality Digest. Used with permission.

Bio:

Dirk Dusharme is Quality Digest’s Editor in Chief. Article is originally published at:

https://www.qualitydigest.com/inside/management-article/made-china-scary-bad-scary-good-part-2-053018.html