Management is not a one-sided coinage, it has an upside and a downside, and all is perceived and judged on the level of the conscious mind. It is about maximising gain while minimising loss in all its forms significant to stakeholders. It is at the basis of commercial activity and inseparably dances together like conjoined associates born out of management exercising choice.

Management is not a one-sided coinage, it has an upside and a downside, and all is perceived and judged on the level of the conscious mind. It is about maximising gain while minimising loss in all its forms significant to stakeholders. It is at the basis of commercial activity and inseparably dances together like conjoined associates born out of management exercising choice.

We may ask, is it like two sides of an evenly matched sports game or does one side dominate the other or take the lead at the management ball? And if so, what are the implications of it being that way and how do we balance prospect and risk? What should motivate a choice amongst alternative paths? Are we formulating problems in the simplest ways and using appropriate concepts and language?

To answer this, we need to get down to fundamentals, and use simple logical concepts and definitions understandable to the person travelling on the Clapham Omnibus, free of mathematics, confusing jargon and snake oil.

If we are ever to properly make sense of managing under uncertainty it must be logical, simple and intuitive. If our brains still end up hurting, then we have failed. But before we look at what satisfies this objective, we should look at muddle-based thinking which pervades much of current management thinking.

Muddle-based thinking

Poor management grammar, illogical, imprecise, ambiguous and often conflicting concepts and definitions retard the understanding and practice of management. It is like the early understanding of ‘science’ before it was consolidated into a coherent, axiomatic and principles based integrated body of knowledge. In contrast, the body of management knowledge is fragmented, and many believe it is not fit for purpose. The management professions are open to accusations of being self-serving rather than serving the greater good and society. Organisations are challenged with having to distinguish between a management product or service that delivers high value and those which are no more valuable than snake oil. The following are typical examples that contribute to muddle-based thinking that threaten the performance of every organisation globally whatever its type and size.

‘Cart before the horse’ is a figure of speech meaning doing things the wrong way around or with the wrong emphasis. The idiom is about confusing cause and effect, and this is what ISO does when it refers to ‘risk and opportunity’ rather than ‘opportunity and risk’.

‘Cart before the horse’ is a figure of speech meaning doing things the wrong way around or with the wrong emphasis. The idiom is about confusing cause and effect, and this is what ISO does when it refers to ‘risk and opportunity’ rather than ‘opportunity and risk’.

Organisation are not created with the primary purpose of taking risk. Apart from potential natural catastrophes, organisations incur risk because of the pursuit and exploitation of opportunities to fulfil the purpose of the organisation. Just as we talk about horse and cart, we should be talking about opportunity and risk indicating that management is principally about exploiting ‘opportunity’ with ‘risk’ as a subordinate but still very critical issue. It is upside takes the lead at the management ball!

Organisations are created, nurtured and maintained to fulfil a purpose that delivers value to customers via goods and/or services. The key component of any business plan is to demonstrate how the organisation will be able to do this viably by exploiting potential opportunities to create value. Its ability to do this depends on the intelligence and creativity of the organisation. An effective business plan will also demonstrate how it will address the avoidance or control of risks arising from the organisation’s creation or its endeavours to exploit one or more opportunities in achieving its objectives.

Risks are a consequence of opportunities and not the other way around. Some people may be uncomfortable with this assertion especially if their role in an organisation is to focus only on one or more aspects of risk. However, it is what each of us naturally does soon after we are born. We traverse the spectrum of positive and negative human emotion as we surf the upsides and downsides of life i.e. situations and things which give rise to feelings of pleasure and/or discomfort or pain. As we continue to explore, learn and become more skilful, we become naturally motivated to maximise the potential for gain (pleasure, happiness et cetera) while minimising the potential for loss (displeasure, harm, pain etc). Our prime motivator is gain and not loss, although we can be overpoweringly demotivated if the potential for loss is major.

Organisations are simply superorganisms, and like people, the choices have to be identified so that goals can be delivered. It is necessary to then assess the prospect(s) of them being realised and the associated risk(s) for each opportunity before deciding which to accept. E.g. when taking a holiday, what opportunities are open to us and what are the associated benefits and risks? Our prime motivation is to seek ways that give us pleasure and only then consider ways that a holiday could go wrong. It is natural to look at several holiday options and compare the prospects and risks associated with each holiday option.

Similarly, when contemplating starting or operating a business, we must start by determining its purpose and then follow by assessing the prospects and risks in meeting this objective. Before adopting any opportunity, the stakeholders need to be satisfied that the potential gain (upside) sufficiently outweighs any potential loss (the downside) and that any potential loss is acceptable to all stakeholders especially those able to exercise influence and power over company operations.

In addition to intelligence and creativity, effective and efficient management critically depends on the way that we define concepts and order our individual and collective thinking. Thinking about ‘opportunity and risk’ rather than ‘risk and opportunity’ is avoiding unhelpful muddle-based thinking and is just one of many examples of the importance of always putting the horse before the cart and respecting the cause and effect nature of the world that we inhabit. As it happens it is something that we all naturally tend to do with varying degrees of proficiency but in managing organisations, it must be orchestrated.

Positive risk

‘Risk management professionals’ and ‘quality professionals’ alike in recent years have been trying to expand their fields of influence across the general conduct of management. Even the accountancy profession is embracing issues beyond pure financial matters. The worth of an acquisition is now being understood to have multiple dimensions and values.

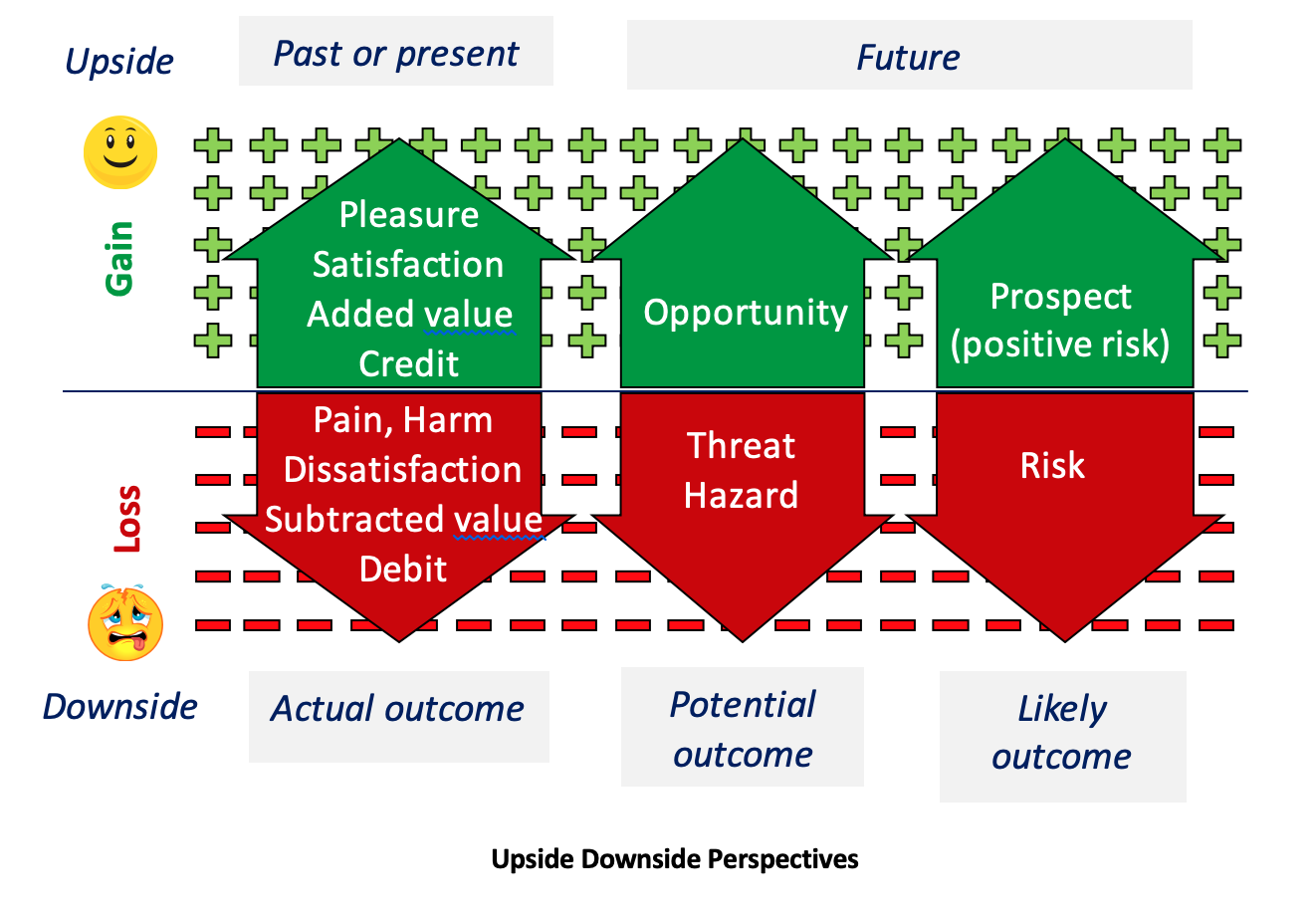

The risk profession has attempted to expand its scope of influence by adopting the term ‘positive risk’ which causes widespread confusion because it is a double-negative. Positive risk means the negation of potential loss i.e. potential gain, so why not give it an appropriate name like prospect which means the opposite of risk. An accountant uses gain and loss terms like credit and debit and not positive debits or negative credits so why is this double negative speak used and tolerated? The risk profession appears to be attempting to brand the upside and downside aspects of management operating under uncertainty in terms of its negative origins with no regard to its impact on effective management.

So why is positive risk being a double negative bad for the practice of management? A double negative is where two forms of negation are used in the same sentence and in English is normally considered bad grammar and to be avoided. The brain hates double negatives because it gives it more work to do in making sense of what has been said – avoiding double negatives simplifies communication and comprehension. Like grammar in general, management grammar is also critically important, but much neglected by management professionals who habitually make simple concepts more complicated than is necessary. The lesson is to avoid double negatives such as ‘positive risk’ in management grammar and keep things simple by using prospect and risk to express upside and downside respectively when operating under uncertainty.

Ironically, the experts on prospect (positive risk) are normally in the sales and marketing department whose job is to turn prospects into sales. They help form strategies and tactics to maximise the likely gain to the company which is essential to the bottom-line!

Irrational risk aversion

We can become irrationally overshadowed or even overwhelmed by fear associated with risk and can impede our acting constructively and achieving optimal outcomes. Successful people are much more focused on the prospects of gain in all its forms and treat the management of the associated risks rationally. We should not be preoccupied with the management of darkness (the absence of light) rather than focusing on how to bring in the light. If the big picture is seen as just avoiding ‘risk’ it will result in management paralysis. It would be like ancient cavemen choosing to remain in the cave while starving to death. The prospect of obtaining food must take the lead and the risk of being eaten in its pursuit must not be allowed to overshadow right action to survive.

Risk appetite

Many risk practitioners talk about the ill-conceived non-sensical and counterintuitive concept of risk appetite which is defined as the level of risk that an organization is prepared to accept in pursuit of its objectives, and before action is deemed necessary to reduce the risk. As humans, we have an appetite expressing how much food we desire but we don’t have a desire for risk because we cannot rationally desire downsides (risks) by definition. Humans therefore cannot have a risk appetite. Food appetite is a minimum to provide satisfaction not a maximum to be tolerated. Why do risk practitioners use language which is counterintuitive and illogical?

Other risk practitioners use the concept of risk tolerability which attempts to balance the upside (prospect) with the associated downsides (risks) and is logical and intuitive. We tolerate a level of risk because the associated potential gain (prospect) sufficiently outweighs it.

However, human behaviour is determined by more than balancing prospect and risk perceptions. We may also have a utility for variation, stability, change, boredom, gambling etc which feed into policy and decision making but it should not be ill-named as risk appetite. Comprehension critically depends on meaningful, precise and intuitive language.

Antidote to muddled-based thinking

The most important thing is to comprehend how current ways of thinking are flawed and to build a coherent, integrated and unified basis of management thinking that is fit for purpose. We may not achieve this overnight but the sooner we address this quest the sooner progress will be made to delivering enhanced value making organisations more successful.

The following subsections suggest a more logical joined-up management thinking to address the upsides and downsides when operating under uncertainty. The big challenge is to carry over the intuitive way that we manage as individuals into the superorganisms that we refer to as organisations. The key thing is that what is managed naturally within the individual must be orchestrated within an organisation via its leadership and management system.

Upside-downside thinking

‘Upside’ and ‘downside’ are commonly used management conceptual classifications for potential satisfactory and unsatisfactory outcomes. Smiley and sad faces are commonly used to link these outcomes to the appropriate positive and negative emotional reactions. We learn this naturally during babyhood as we explore and traverse the nature of reality and attempt to optimise our happiness. This exploration of reality is motivated by our basic needs and was elegantly modelled by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in 1943. We are continually presented with opportunities to satisfy needs but also with related threats and is the principal basis of the Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) strategic planning tool.

Prospect and risk – upsides and downsides operating under uncertainty

Prospect and risk are the likelihood and degree of potential gain and likely loss respectively and is in effect deterministic ‘quality’ operating under uncertainty. We desire a quality of life, quality goods and quality services etc but their delivery and associated outcomes cannot be realised with 100% certainty. However, in some instances the small departure from 100% can be ignored if the consequence is not significant to stakeholder satisfaction. However, where this is not the case quality must be managed within an arena of uncertain gain and loss i.e. prospect and risk respectively.

Irrespective of the degree of uncertainty the upsides and downsides cannot be managed in isolation of each other and the upside always takes the lead at the management ball..

Why are upsides and downsides inseparable?

If upsides are desirable and downsides undesirable, why can we just not seek out the upsides and leave the downsides? If only we could, but the world is subject to Natural Law and the upsides and downsides pervade all human activity and actions inextricably interlinked on the level of the conscious human mind where judgements of good and bad are made. Amongst other things, we can have conflicting freedoms of action, needs, expectations and aspirations creating unavoidable gain-lose situations. E.g. in a competitive environment, an organisation can win new customers while another loses them. Innovation can bring potential benefits but also have negative outcomes and sometimes they are unforeseen and unintended. An action to improve the environment may restrict a habitat for a human family to live in. Whenever an option is identified for potential upsides (gain) from a given perspective, there are inevitably associated potential downsides (losses). One stakeholder’s upside can be another’s downside! Stakeholders may also disagree about how large a given upside or downside is – it is all relative to the stakeholder individual or group.

More technically, this may be understood in terms of the individual’s or group’s utility which is a measure of perceived worth or value. Holiday makers may have a low utility for rain while a farmer’s utility may be high. While utility can be diverse in some instances it can significantly converge e.g. the worth of nurturing and not harming humankind and protecting the global environment. This is a very strong shared upside and much of regulated risk control reflects this strong societal value. Hence basic health and safety, environment, human rights risks controls are generally established as non-negotiable. However, when the potential degree of upside is significantly high, we may tolerate an increased downside.

Closely shared utility also tends to align with that of religious organisations, ethical frameworks and that of the ‘Ultimate Stakeholder’.

This is the complex reality of the real world which is often ignored when using simplistic analytical models. While modelling brings understanding and insights, we need to be conscious that whatever we apply has limitations and should not be used to illegitimately justify an action.

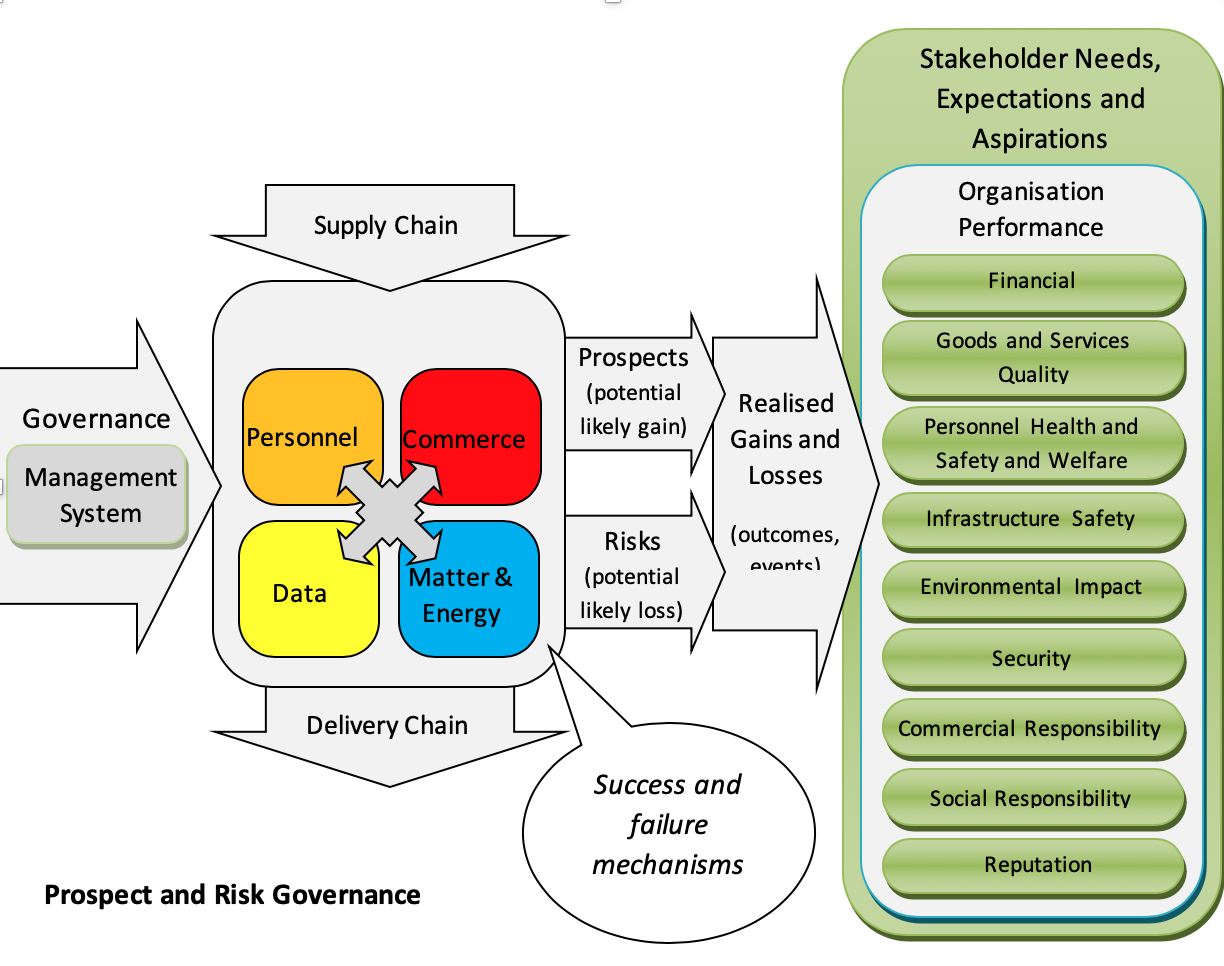

If we are to continually improve the theory and practice of management, we need logical valid axioms at its basis. A clear understanding of the origin and nature of upside and downside thinking needs to be part of it. The ‘Prospect and Risk Governance’ figure above gives an insight into how upsides and downsides may be managed in an integrate way.

What is acceptable prospect and risk?

Risk tolerance has no meaning unless it is linked to the related benefit (likely gain). We only tolerate a likely loss (risk) if the likely gain (prospect) sufficiently outweighs it. We take the significant risks of driving a car because the benefits are so valuable to us and society. Of course, If risks are low, the effort and time involved in managing them is generally accepted as not worth the effort.

Organisations exist to fulfil a purpose and mission but in order to achieve this, the organisation must address uncertainties contained in the prospects and risks associated with equitably satisfying the needs, expectations and aspirations of its stakeholders, and the uncertainties and variations in its internal structures and processes and in the external operational environment.

Prospect, risk and uncertainty pervade structures and processes relating to an organisation’s:

- Strategy, tactics and operations,

- Internal and external environment,

- People, commerce, data, matter and energy, and suppliers,

- Stakeholder needs, expectations and aspirations, including conflicts.

Good management requires effective and efficient decision-making and the direction and guidance of the structures and processes that deliver goods and services. This uncertainty must be considered in order to make optimal decisions relating to the impacts of operations on stakeholders.

Where the uncertainty of potential outcomes is significant, formal prospect and risk management assessment can help facilitate better judgements and decisions. It also makes the processes more transparent to stakeholders and aids independent review and approval where this is applicable.

An organisation must attempt to maximise prospect while minimising risk. As a minimum, there should be an aggregate net financial gain that is acceptable to the relevant stakeholders and will sustain the financial viability of the organisation. However, this is only part of what satisfies stakeholders – they may have personal values that are expressed through their needs, expectations and aspirations. Potentially these may span all the facets of an organisation’s performance such as finance, goods and service quality, personnel health, safety and welfare, infrastructure safety, environmental, security, commercial integrity, social integrity and reputation.

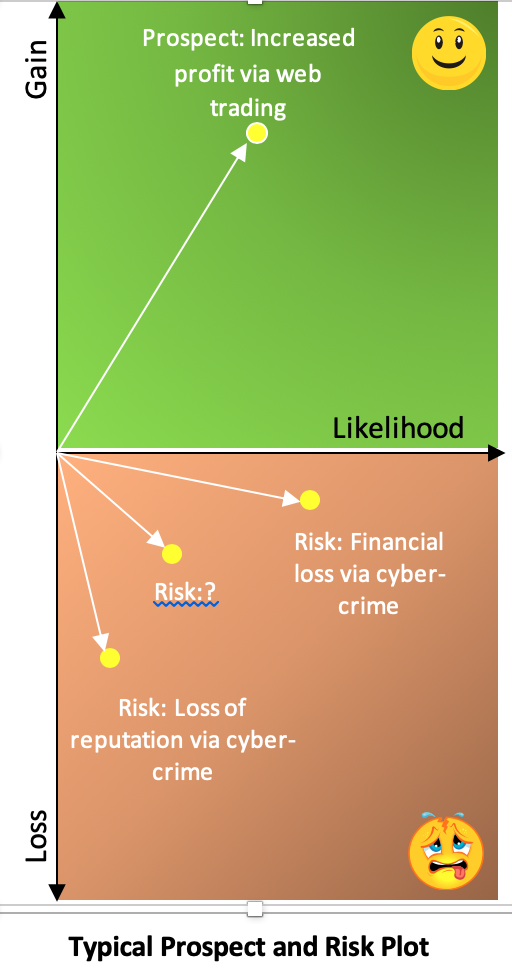

The organisation must ensure that not only the net likely gain is acceptable but also that any individual prospect or risk is acceptable as judged rationally or irrationally by any stakeholder. This is shown conceptually in the example Prospect and Risk Plot. It shows how prospects and risks can be plotted graphically on a diagram using coordinates representing gain/loss and likelihood of realisation. Curves may be plotted representing prospect or risk functions where the likelihood of various levels of gain/loss needs to be considered. An example of this is the plotting of natural disasters such as earthquakes etc. with different severities.

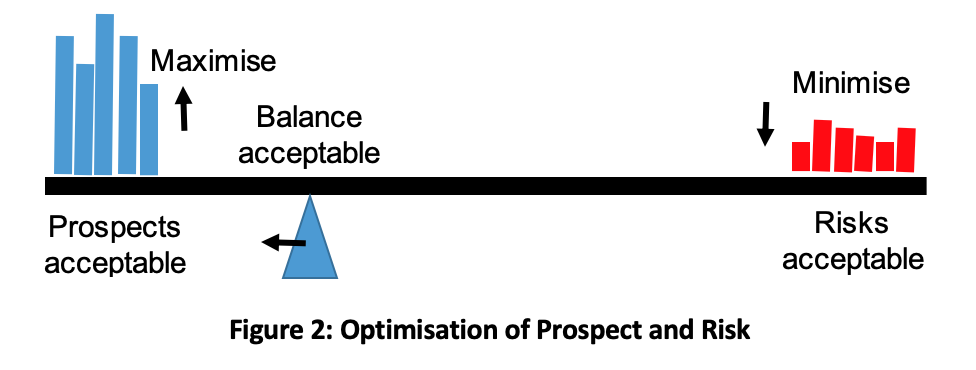

The optimisation of prospect and risk is shown conceptually in the figure above. Regarding any identified option, the organisation should ensure that:

- Stakeholder needs, expectations and aspirations and their potential to exercise power over the organisation’s activity is sufficiently understood, including that exercised through legislation,

- That the prospect(s) are sufficiently rewarding to warrant the commitment of resources,

- Any individual associated risk is acceptable to the relevant stakeholder(s) or may be equitably agreed by stakeholders,

- Overall, the net prospect is acceptable to the relevant stakeholders and will help sustain the organisation,

- Unless it is the only option, it is the best overall option when compared with others.

Re-educating managers and professionals

This article demonstrates that we can manage when operating under uncertainty in a more joined-up way conceptually and practically. It allows problems to be defined more logically and completely and facilitate better decision processes.

Organisations are not created to take risks. Risks are just the inevitable downside of seeking prospects to deliver an organisation’s purpose to equitably satisfy stakeholders while making the best use of resources [principle of integrated management].

We should be teaching managers and professionals how to be successful and not exhaustive lessons in failures to be avoided, although the nature of failure needs to be understood. We need to know how to avoid and minimise loss but not in isolation of the quest for prospects that deliver the purpose of the organisation and value. In order to be successful, managers need integrated 20:20 upside (prospect) and downside (risk) vision, understand the universal principles of management and the methodologies and tools to realise it. This needs a fundamental change in learning and development programs delivered via a universal simplified set of concepts and definitions. This cannot be achieved overnight but those who do it best and quickest will reap the rewards earliest and gain a competitive advantage.

We need to establish a integrated management learning and development frameworks that not only enhances the performance of management but also support the continual improvement of management theory and practice and reverse its fragmentation.

The universal management system standard MSS 1000 is based on the above integrated philosophy and may be freely downloaded via www.integratedmanagement.info/mss-1000. In contrast to ISO standards, it contains a full set of unified management definitions, , enabling precise communication and better comprehension of integrated management.

The figures contained in this article have been reproduced from Managing Data in an Evolving World – A guide for good data governance.

Biography – IAN DALLING

Ian Dalling DipEE, BA (Hons), CEng, MIMechE, MIET, MIOSH, FCIQ, CQP, RSC Chartered Electrical and Mechanical Engineer and Integrated Management Practitioner

Ian’s 50 years of experience has spanned design, construction, commissioning, operation, and decommissioning of nuclear power plants and other industry sectors. While at CEGB/Nuclear Electric, he was a senior authorised person for nuclear, mechanical and electrical systems up to 400 kV and held posts in operations, commissioning, management services, planning and quality assurance.

From 1990, he was a quality and risk management consultant with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. He managed the peer review of the decommissioning safety case for the UK Steam Generating Reactor, was the quality manager for a European Notified Body administering product safety regulations, and worked on a variety of safety cases and management systems for major organisations. He served on the European Process Safety committee and the British Standards Committee that developed the occupational safety and health standard (BS 8800:1996). He was a member of an international team that reviewed the safety management arrangements of the Lithuanian Ignalina RBMK nuclear power plant following the Chernobyl accident.

He has operated his own quality and risk management consultancy since 1999 with clients in the nuclear, construction, rail, oil and gas, medical devices, medical services and laboratory services sectors in the UK and overseas. He chairs the CQI Integrated Management Special Interest Group, which produced the universal management system standard MSS 1000:2014.