Some interesting points about how organizations apply current standards such as Business Impact Analysis (Assessment) (BIA), risk assessment methodologies, compliance and planning has been written about lately. Each author presents good arguments for their particular methodology. Nassim Taleb created the concept of “Antifragile” because he did not feel that “resilience” adequately described the need for organizations to be ready to absorb the impact of an event and bounce back quickly.

Some interesting points about how organizations apply current standards such as Business Impact Analysis (Assessment) (BIA), risk assessment methodologies, compliance and planning has been written about lately. Each author presents good arguments for their particular methodology. Nassim Taleb created the concept of “Antifragile” because he did not feel that “resilience” adequately described the need for organizations to be ready to absorb the impact of an event and bounce back quickly.

According to McKinsey & Co., “Resilient executives will likely display a more comfortable relationship with uncertainty that allows them to spot opportunities and threats and rise to the occasion with equanimity.” Adaptive Business Continuity, according to its manifesto, is an approach for continuously improving an organization’s recovery capabilities, with a focus on the continued delivery of services following an unexpected unavailability of people, locations, and/or resources.

There seems to be a lot of controversy about some of the tenets of these various approaches.

In his book, “Antifragile Things That Gain From Disorder” Nassim Taleb (Prologue states: “Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk and uncertainty. Antifragility is beyond resilience and robustness.”

Taleb also wrote:

To have “skin in the game” is to have incurred risk (monetary or otherwise) by being involved in achieving a goal. In the phrase, “skin” is a synecdoche for the person involved, and “game” is the metaphor for actions on the field of play under discussion.

Of course, this has been one of my observations for a long time – organizations do not do a in depth assessment of risk or business impacts. They choose to limit their focus in these areas. We tend to see only that which we choose to see, hence the limitations of the BIA, risk management practices and planning practices (take your choice regarding planning approaches). When it comes to these practices, we preach “best practices” to adherents; yet few know the origins of the concept of “best practices”. Compliance guidance is also flawed in that most of it is reactionary to an event that has occurred; such as, Bophol, India; Exxon Valdez, BP Deepwater Horizon, Three Mile Island, etc.

Test Yourself

Here are twelve questions from Hans Rosling’s book “Factfulness”. I have omitted one question from the original list as it requires a series of maps in order to be answered. Take a piece of paper and answer each question. The correct answers are found in the “Reference” section herein. Now, no cheating – so don’t go look at the answers before you complete your answers. Rosling also points out that, you may not be able to beat a chimpanzee when it comes to the test. It seems that we may be systematically misinterpreting a lot of the things we are supposed to be expert about. Are we susceptible to the over dramatic risks that we face (i.e., the asteroid or meteor that could potentially destroy our data center)?

- In all low-income countries around the world today; how many girls finish primary school?

A: 20 percent

B: 40 percent

C: 60 percent

- Where does the majority of the world population live?

A: Low-income countries

B: Middle-income countries

C: High-income countries

- In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has:

A: almost doubled

B: remained more or less the same

C: almost halved

- What is the life expectancy of the world today?

A: 50 years

B: 60 years

C: 70 years

- There are 2 billion children in the world today, aged 0 to 15 years old. How many children will there be in the year 2100 according to the United Nations?

A: 4 billion

B: 3 billion

C: 2 billion

- The UN predicts that by 2100 the world population will have increased by another 4 billion people. What is the main reason?

A: There will be more children (age below 15)

B: There will be more adults (age 15 – 74)

C: There will be more very old people (age 75 and older)

- How did the number of deaths per year from natural disasters change over the last hundred years?

A: More than doubled

B: Remained about the same

C: Decreased to less than half

- How many of the world’s 1-year-old children today have been vaccinated against some disease?

A: 20 percent

B: 50 percent

C: 80 percent

- Worldwide 30-year old men have spent 10 years in school, on average how many years have women of the same age spent in school?

A: 9 years

B: 6 years

C: 3 years

- In 1996 tigers, giant pandas and black rhinos were all listed as endangered. How many of these three species are more critically endangered today?

A: Two of them

B: One of them

C None of them

- How many people in the world have some access to electricity?

A: 20 percent

B: 50 percent

C: 80 percent

- Global climate experts believe that, over the next 100 years, the average temperature will:

A: Get warmer

B: Remain the same

C: Get colder

How did you do? According to Rosling’s experience in administering this and other tests, probably not too well. Why? Could it be that we give too much credence to what we think we know instead of investigating and getting more fact based about our activities? Realize that while the asteroid and meteor pose real threats to data centers, etc., the reality is that we are daily dealing with data disruptions on a small scale. These interruptions are cumulative in terms of time, money and the human resources required to fix them.

In my article, “Are We Missing the Point of Risk Management Activities” (2016), I offered three definitions or categories of risk. I present them briefly below. The complete article is available on the Internet.

Strategic Risk: A possible source of loss that might arise from the pursuit of an unsuccessful business plan. For example, strategic risk might arise from making poor business decisions, from the substandard execution of decisions, from inadequate resource allocation, or from a failure to respond well to changes in the business environment. Read more: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/strategic-risk.html. According to the post on Simplicable entitled, “22 Strategic Risks”, posted by Anna Mar, February 02, 2013 (http://business.simplicable.com/business/new/22-strategic-risks).

Operational Risk: The Basel II Committee defines operational risk as: “The risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.” According to Simplicable, Operational risk is the chance of a loss due to the day-to-day operations of an organization. Every endeavor entails some risk, even processes that are highly optimized will generate risks. Operational risk can also result from a break down of processes or the management of exceptions that aren’t handled by standard processes. It should be noted that some definitions of Operational risk suggest that it’s the result of insufficient or failed processes. However, risk can also result from processes that are deemed sufficient and successful. In a practical sense, organizations choose to take on a certain amount of risk with every process they establish. The following are a few examples of operational risk.

Tactical Risk: Tactical Risk is the chance of loss due to changes in business conditions on a real time basis. Tactics differ from strategy in that they handle real time conditions. In other words, a strategy is a plan for the future while a tactic is a plan to handle real world conditions as they unfold. As such, tactical risk is associated with present threats rather than long term conditions. Tactics and strategy are both military terms. Military organizations primary view tactical risk as the conditions on a battlefield. An army may identify strategic risks before a battle but tactical risks can only be identified as they unfold. The following are a few examples of tactical business risks.

Please refer to the article for more detail and examples of each of the risk categories.

Misconceptions – Risks, Threats, Hazards, Vulnerabilities (RTHV) Underlying Planning or Lack Thereof

To assess or not to assess? Standard accepted practices in risk management and business continuity planning have always stressed the need for risk assessment and for the Business Impact Analysis (Assessment) BIA as a fundamental step in the planning process. Experience has shown that these (risk assessment and BIA) often take too long to complete (time) and in the end are actually quite incomplete. In addition, the three levels that I have mentioned – Strategic, Operational and Tactical have changing goals and objectives based on business results, operations and management focus.

The Adaptive approach to continuity planning lists ten principles:

- Deliver Continuous Value

- Document only for Mnemonics

- Employ Time as a Restriction, Not a Target

- Engage at many Levels within the Organization

- Exercise for Improvement, not for Testing

- Learn the Business

- Measure and Benchmark

- Obtain incremental direction from Leadership

- Omit Risk Assessments and Business Impact Analyses

- Prepare for Effects, not Causes

Where one controversy starts is with the principle of omitting Risk Assessments (RA) and Business Impact Analysis (BIA). It is prudent to conduct a business impact analysis (assessment) (BIA) and to constantly assess the risk landscape to be able to link apparently non related issues, events, etc., to create a mosaic of risk complexity that can be addressed at multiple levels. In probability theory and mathematical physics, a random matrix (sometimes stochastic matrix) is a matrix-valued random variable—that is, a matrix some or all of whose elements are random variables.

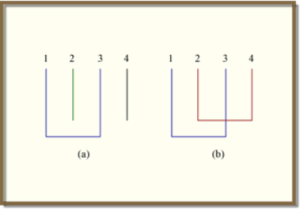

The power of infinite random matrix theory comes from being able to systematically identify and work with non-crossing partitions (as depicted on the left). The figure on the right depicts a crossing partition which becomes important when trying to understand the higher order terms which infinite random matrix theory cannot predict. (Figure by Prof. Alan Edleman.)

The power of infinite random matrix theory comes from being able to systematically identify and work with non-crossing partitions (as depicted on the left). The figure on the right depicts a crossing partition which becomes important when trying to understand the higher order terms which infinite random matrix theory cannot predict. (Figure by Prof. Alan Edleman.)

It would be wise to begin to consider random matrix theory with respect to risk identification and assessment. The complexity we face today with a globalized society is that risks are shared more and more, even though we have less and less awareness of the manner in which risks are shared. A good example of this is the international supply chain system. While organizations have their own supply chain; the combination of all organizations supply chains creates an entirely different risk exposure. Just think in terms of movement in the supply chain. Shippers (air, rail, ship, overland, etc.) are all trying to maximize their resources from an efficiency perspective. This has led the shipping industry to build mega-container ships, which require different portage and logistics capabilities. Shippers are handling multiple organization’s supply chains, moving products to a wide audience of customers. While efficiency is increased, risk is also greater due to the potential for a “single point of failure” resulting in the loss of the ship and cargoes.

All that said, the traditional BIA and RA need to be rethought so that the process does not get bogged down in the details that really have little impact on the business. By this I do not mean that the results of how many workstations, computers, printers, copy machines and other output should be discarded. However, if you have a purchasing/logistics department this information should be readily available from their records.

Effective continuity and risk management programs cannot be designed to satisfy everyone. Instead, they need to clearly identify how the implementation will support the achievement of the organization’s goals and objectives (strategic). Once planners and risk managers understand what is needed to sustain business operations during a disruption they can begin to identify risks and potential business impacts more readily and rapidly. This is where the recent McKinsey & Co., article “Bridging the gap between a company’s strategy and operating model” brings some relevance into play. Here is a quote from the article:

“Once a company understands where it creates the most value, it must identify the specific institutional competencies it needs. This usually means getting specific about what it needs to be able to do to deliver on the most important parts of the value chain.”

If you really think about that statement, it is the essence of the focus of business continuity planning and risk management. Understand where we create the most value – now assess the risks and potential business impacts to a disruption of the ability to create value; build plans that are flexible and adaptable to the situation and the resources available, constantly monitor and assess risks (think like a commodities trader) to create Risk Parity.

Risk Parity is a balancing of resources to a risk. You identify a risk and then balance the resources you allocate to buffer against the risk being realized (that is occurring). This is done for all risks that you identify and is a constant process of allocation of resources to buffer the risk based on the expectation of risk occurring and the velocity, impact and ability to sustain resilience against the risk realization. You would apply this and then constantly assess to determine what resources need to be shifted to address the risk. This can be a short term or long-term effort. The main point is that achieving risk parity is a balancing of resources based on assessment of risk realization.

Risk Parity is not static as risk is not static. When I say risk is not static, I mean that when you identify a risk and take action to mitigate that risk, the risk changes with regard to your action. The risk may increase or decrease, but it changes due to the action taken. You essentially create a new form of risk that you have to assess with regard to your action to mitigate the original risk. This can become quite complex as others also will be altering the state of the risk by taking actions to buffer the risk. The network that your organization operates in reacts to actions taken to address risk (i.e., “Value Chain” – Customers, Suppliers, etc.) all are reacting and this results in a non-static risk.

Resources Today—and Where?

I will quote again from McKinsey & Co. in the May 2019 article, “Bubbles pop, downturns stop”:

“Your business context is and will remain uncertain. But if you get moving now, you can ride the waves of uncertainty instead of being overpowered by them.”

Here again is the essence of what risk management and business continuity planning should focus on. It is uncertainty that will drive much of the reactive response to a disruptive event. Here again, the Adaptive approach has two principles that start to address this uncertainty. One of the principles states: “obtain incremental direction from leadership”. Leadership needs to be involved more than incrementally when responding to disruption that threatens the organization’s ability to execute on its goals and objectives. This does not mean micro-managing the response. It means that leadership is informed and can provide a higher level of direction based on a broader understanding of the impacts to business operations. The other principle states: “prepare for effects, not causes”. Effects are often times immediate, generally are short term (once the fire is out and damage assessed, the recovery phase starts, right?). Consequences may not be immediately apparent (i.e., asbestos exposure, agent orange exposure, etc.) and can lead to long-term crisis operations.

Here is where the potential value of business continuity and risk management can be leveraged. The organization needs to have a readily available pool of resources (human, financial, equipment, etc.) to continue the business operation. While being insured (Business Interruption, Contingent Business Interruption insurance, etc.) is important, having the ability to reconstitute the business operation is critical. Insurance is not a guarantee of immediate payment of claims.

Part of the planning and risk management process should be to answer what the distinctive institutional capabilities are and where they are located. Questions posited in the McKinsey article (cited above) include answering:

“Which functions and capabilities should reside within the corporate center versus within the business units? Who should be empowered to make key decisions and manage the budget or allocation of resources? What are the most critical roles within the organization, and do we have the best people assigned to those roles?”

According to the McKinsey article “Bubbles pop, downturns stop”, a resilience nerve center aims to do three things well:

- monitora small number of material risks and use stress tests to orient the company, early, toward downturn-related economic impacts

- decidehow the organization will manage these impacts faster

- executeby organizing teams into agile, cross-functional units that drive toward clear outcomes, create forums for faster executive decision making, and monitor the results through value-based initiative tracking

Getting past the limitations of traditional performance approaches oriented around head count and cost will require fresh thinking about boosting productivity.

“Disruption happens, we cannot really control its occurrence; however, the way that we respond is something we can control. The consequences to disruption can, in many ways, be minimized by foresight and astute analysis of those things not readily connected.”

Concluding Thoughts

Being in compliance does not negate risk. I think that we have to overcome the compliance mentality and to understand the nature of risk better. I will conclude by offering the following seven points:

- Recognize that your risks are not unique

Risks are shared by every organization regardless of if they are directly or indirectly affected. To treat your risks as unique, is to separate your organization from the interconnected world that we live in. If you have a risk, you can be assured that that same risk is shared by your “Value Chain” and those organizations outside of your “Value Chain”.

- Whatever you do to buffer the risk has a cascading effect (internally and externally)

Your organization needs to be in a position of constantly scanning for changes in the risk environment. When you buffer a risk, you create an altered risk. By altering the risk exposure, your network (i.e., “Value Chain”) now has to address the cascade effects. The same is true for your organization; as the “Value Chain” buffers risk it is altered and you are faced with a different risk exposure.

- Risk changes as it is being buffered by you and others

As mentioned above, risk changes, it alters, it morphs into a different risk exposure when you or others do something to buffer against the risk being realized. Your challenge is to recognize the altered form of risk and determine how to change your risk buffering actions to protect against the risk being realized and your organization not having the right risk treatment in place.

- Risk is not static

If we look at commodities trading, we begin to understand the nature of speed and its ability to move throughout an organization rapidly. Commodities are complexity personified. Markets are large (global) in scale and trading is nearly constant (i.e., 24 X 7 – 24 hours a day and 7days a week). This makes identifying and managing risk a challenge that can be daunting to many. In many conversations with commodity traders I came to conclusion that their ability to see risk as a continuum, constantly changing, opaque and rapid in its impact creates a mindset of constant vigilance and offsetting of risks.

- Risk is in the future not the past

During the cold war between the United States of America and the former Soviet Union, there were thousands of nuclear warheads targeted at the antagonists and their allies. The result, the concept of mutually assured destruction was created. The term was used to convey the idea that neither side could win an all-out war; both sides would destroy each other. The risks were high; there was a constant effort to ensure that “Noise” was not mistaken for “Signal” triggering an escalation of fear that could lead to a reactive response and devastation. Those tense times have largely subsided, however, we now find ourselves in the midst of global competition and the need to ensure effective resilience in the face of uncertainty.

We are faced with a new Risk Paradigm: Efficient or Effective? Efficiency is making us rigid in our thinking; we mistake being efficient for being effective. Efficiency can lead to action for the sake of accomplishment with no visible end in mind. We often respond very efficiently to the symptoms rather than the overriding issues that result in our next crisis. Uncertainty in a certainty seeking world offers surprises to many people and, to a very select few, confirmation of the need for optionality.

It’s all about targeted flexibility, the art of being prepared, rather than preparing for specific events. Being able to respond rather than being able to forecast, facilitates early warning and proactive response to unknown Uknowns.

I think that Jeffrey Cooper offers some perspective: “The problem of the Wrong Puzzle. You rarely find what you are not looking for, and you usually do find what you are looking for.” In many cases the result is irrelevant information.

Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber would define this as a Systemic Operational Design (SOD) problem – a “wicked problem” that is a social problem that is difficult and confusing versus a “tame problem” not trivial, but sufficiently understood that it lends itself to established methods and solutions. I think that we have a “wicked problem”.

As Milo Jones and Philippe Silberzahn in their book “Constructing Cassandra: Reframing Intelligence Failure at the CIA, 1947–2001” write, “Gresham’s Law of Advice comes to mind: “Bad advice drives out good advice precisely because it offers certainty where reality holds none”” (page 249).

The questions that must be asked should form a hypothesis that can direct efforts at analysis. We currently have a “threat” but it is a very ill defined “threat” that leads to potentially flawed threat assessment; leading to the expending of effort (manpower), money and equipment resources that might be better employed elsewhere. It is a complicated problem that requires a lot of knowledge to solve and it also requires a social change regarding acceptability.

Experience is a great teacher it is said. However, experience may date you to the point of insignificance. Experience is static. You need to ask the question, “What is the relevance of the experience to your situation now?”

- The world is full of risk: diversify

When it comes to building your risk and/or business continuity program, focusing on survivability is the right approach, provided you have thoroughly done your homework and understand what survivability means to the organization. The risks to your organization today are as numerous as they are acute. Overconcentration in any one area can result in complete devastation.

- Recognize Opacity and Nonlinearity

The application or, misapplication, of the concept of a “near miss” event has gained increasing popularity and more importance than it should have. A risk manager’s priorities should be based on recognizing the potential consequences of a “near miss” event, not on determining the cause of the event. While causality is important, due to today’s complexity and the nonlinearity of events, determining causality can become an exercise in frustration. Instead we need to focus on consequence analysis and recognize that as risks evolve change begins to occur, collateral factors come into play, uniqueness is created in the way that the evolution of risk occurs. The nonlinear evolution of risks combined with reactions to events to transform potential risk consequences.

I don’t disagree that analysis of “near miss” events can benefit the organization and facilitate progress in reducing risk exposures in the future. Investigating “near misses” is often hampered by the nonlinearity and opaque nature of the event itself. Thereby rendering any lessons learned less than helpful in reducing risk exposure and more importantly risk realization consequences. “Near miss” events will not have exactly the same chain of causality as a risk event that actually materializes into an impact with unforeseen consequences.

Recognizing and analyzing all “near miss” events isn’t a realistic option. This is due in part to the fact that we do not experience events uniformly. A “near miss” to you might be a non-event to someone who deals with similar situations regularly (see my article: “Transparent Vulnerabilities) as the event becomes transparent to them.

Take a look at the exhibit below from McKinsey (“Bubbles pop, downturns stop”) and then take a hard look at your current risk management and business continuity programs. Now, ask yourself, “Do we address any of this in our current business continuity planning/risk management programs?

Geary Sikich – Entrepreneur, consultant, author and business lecturer

Contact Information: E-mail: G.Sikich@att.net or gsikich@logicalmanagement.com. Telephone: 1- 219-922-7718.

Geary Sikich is a seasoned risk management professional who advises private and public sector executives to develop risk buffering strategies to protect their asset base. With a M.Ed. in Counseling and Guidance, Geary’s focus is human capital: what people think, who they are, what they need and how they communicate. With over 25 years in management consulting as a trusted advisor, crisis manager, senior executive and educator, Geary brings unprecedented value to clients worldwide.

Geary is well-versed in contingency planning, risk management, human resource development, “war gaming,” as well as competitive intelligence, issues analysis, global strategy and identification of transparent vulnerabilities. Geary has developed more than 4,000 plans and conducted over 4,500 simulations from tabletops to full scale integrated exercises. Geary began his career as an officer in the U.S. Army after completing his BS in Criminology. As a thought leader, Geary leverages his skills in client attraction and the tools of LinkedIn, social media and publishing to help executives in decision analysis, strategy development and risk buffering. A well-known author, his books and articles are readily available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and the Internet.

References

https://innolution.com/resources/glossary/antifragile

https://innolution.com/blog/agile-risk-management-antifragile

https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mathematics/18-338j-infinite-random-matrix-theory-fall-2004/

https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/23/079/23079901.pdf?r=1&r=1

https://www.adaptivebcp.org/manifesto.php

Apgar, David, Risk Intelligence – Learning to Manage What We Don’t Know, Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

Davis, Stanley M., Christopher Meyer, Blur: The Speed of Change in the Connected Economy, (1998).

Dionne, Georges; Risk Management: History, Definition and Critique (March 2013 – CIRRELT-2013-17);

Edelman, Dr. Alan; Crossing partition figure, Infinite Random Matrix, Random Matrix Theory, MIT Course Number 18.338J / 16.394J

Jones, Milo and Silberzahn, Philippe, Constructing Cassandra: Reframing Intelligence Failure at the CIA, 1947–2001, Stanford Security Studies (August 21, 2013) ISBN-10: 0804785805, ISBN-13: 978-0804785808

Kami, Michael J., “Trigger Points: how to make decisions three times faster,” 1988, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-033219-3

Klein, Gary, “Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions,” 1998, MIT Press, ISBN 13 978-0-262-11227-7

Marks, Norman; Time for a leap change in risk management guidance, November 5, 2016

Rosling, Hans with Rosling, Ola and Ronnlund, Anna Rosling; Factfulness Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things are Better Than You Think; Flatiron books, New York, New York. ISBN 978-1-250-10781-7 (hardcover), ISBN 978-1-250-12381-7 (ebook). First edition April 2018

Test Questions Answers: 1 – C, 2 – B, 3 – C, 4 – C, 5 – C, 6 – B, 7 – C, 8 – C, 9 – A, 10 – C, 11 – C, 12 – A

Sikich, Geary W., Graceful Degradation and Agile Restoration Synopsis, Disaster Resource Guide, 2002

Sikich, Geary W., “Integrated Business Continuity: Maintaining Resilience in Times of Uncertainty,” PennWell Publishing, 2003

Sikich, Geary W., “Risk and Compliance: Are you driving the car while looking in the rearview mirror?” 2013

Sikich, Geary W., ““Transparent Vulnerabilities” How we overlook the obvious, because it is too clear that it is there” 2008

Sikich, Geary W., “Risk and the Limitations of Knowledge” 2014

Sikich, Geary W., “Can You Calculate the Probability of Risk?” 2016

Sikich, Geary W., “Are We Missing the Point of Risk Management Activities?” 2016

Sikich, Geary W., “Complexity: The Wager – Analysis or Intuition?” 2015

Sikich, Geary W., Remme, Joop “Unintended Consequences of Risk Reporting” 2016, Continuity Central

Tainter, Joseph, “The Collapse of Complex Societies,” Cambridge University Press (March 30, 1990), ISBN-10: 052138673X, ISBN-13: 978-0521386739

Taleb, Nicholas Nassim, “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable,” 2007, Random House – ISBN 978-1-4000-6351-2, 2nd Edition 2010, Random House – ISBN 978-0-8129-7381-5

Taleb, Nicholas Nassim, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets, 2005, Updated edition (October 14, 2008) Random House – ISBN-13: 978-1400067930

Taleb, N.N., “Common Errors in Interpreting the Ideas of The Black Swan and Associated Papers;” NYU Poly Institute October 18, 2009

Taleb, Nicholas Nassim, “Antifragile: Things that gain from disorder,” 2012, Random House – ISBN 978-1-4000-6782-4

Taleb, Nassim N., Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life, February 27, 2018 ISBN-10: 042528462X, ISBN-13: 978-0425284629

Threatened by Dislocation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eWKDGamtoIE

www.risk.net/operational-risk…