A widespread desire to improve organizational performance may be sated by focusing on a key set of executive imperatives—necessary and high priority actions. Personal experiences reveal that an essential focus on creating excellence in people, processes, and the working environment reaps tremendous benefits and enables executives and their organizations to achieve desired objectives.

A widespread desire to improve organizational performance may be sated by focusing on a key set of executive imperatives—necessary and high priority actions. Personal experiences reveal that an essential focus on creating excellence in people, processes, and the working environment reaps tremendous benefits and enables executives and their organizations to achieve desired objectives.

From our long careers as program managers in high tech new product development and from working with a wide variety of organizations world-wide, we observed a wealth of executive practices, some effective for improving organizational performance and many not. A distillation of executive imperatives provides fodder for achieving more optimized results.

From our long careers as program managers in high tech new product development and from working with a wide variety of organizations world-wide, we observed a wealth of executive practices, some effective for improving organizational performance and many not. A distillation of executive imperatives provides fodder for achieving more optimized results.

A search for and concerted effort to improve project management is an internal activity within an organization aimed at operational effectiveness. This is a necessary but not sufficient effort to create a truly excellent organization. What is also required is an overt, explicit effort to achieve successful outcomes THROUGH project management. When executives in an organization come to recognize the importance and phenomenal contribution of project, program and portfolio management, they benefit from bountiful harvests.

Creating excellence IN project management occurs when sponsors appoint appropriate project leaders and they apply methodologies, viewpoints, insights, and leading practices to optimize project-based work. This goal is necessary because projects are the means to achieve almost anything in every organization. Without good project, program, and portfolio management, achieving results is tenuous. Traditional efforts are not sufficient in an environment where internal and external forces are both driving and restraining performance in an accelerating manner. Organizational maturity requires that executives reduce organizational “toxins” and create “green” organizations, using a systemic approach.

Assess the Environment

The imperative facing executives in all organizations is not only to embark on a quest to manage project management processes, but also to create a “green ecosystem” as an environment that encourages project-based work and to eliminate pollutants and “toxic” actions that demotivate project managers and their teams. This means searching with unrelenting curiosity for leading practices. It also means, when these practices are revealed, that executives are prepared to take action.

Progressively improving practices, also called organizational maturity, requires that project leaders and management reduce organizational “toxins” and create “green” organizations. “Green” in this context extends the physical, tangible thinking about project work into the non-physical, intangible personal working relationships that affect our working environments. In this sense, in an “ecosystem” that allows good project management to grow, “green” is good.

Without the “green” foundation, organizations experience failures, overruns, and dissatisfied stakeholders. These “toxic” project environments are usually permeated by political practices that create uneasiness and frustration among all except those who wield these negative practices with power.

A “green ecosystem” creates an environment for consistent, predictable, and sustainable success. It eliminates “toxic” substances and provides projects with a physical and mental context that allows them to prosper. This allows management to focus on overall organizational success, not just on individual project performance. People then feel like they are constantly contributing to organizational and personal knowledge and creating growth.

Executive Actions

Senior managers often insist on doing things their way, even though they are new to that position or portion of the business and do not understand project management. People who apply sound project management practices and achieve consistent successes are extremely valuable, if not in scarce supply. The executive imperative is to tap the collective wisdom, recognize talented individuals within the organization, and get out of their way.

Common in many situations, projects operate with little formal control or have been given solutions to produce that were unclear or perhaps even wrong. This amounts to working on a solution in search of a problem. Such situations invariably create resistance from stakeholders. Taking time to interview key stakeholders and as many senior managers as possible surfaces real problems that need solving and identifies true definitions of success that meet stakeholder requirements.

Recognize that when people accept a project assignment without a clear problem statement that everyone agrees upon, they are being set up for failure. It will take courage, time, and effort on their part to push back. Effective negotiating skills are necessary; if not present, support training to develop these essential skills.

The executive imperative is to engage in negotiations, clearly define problems, prioritize the importance of solutions to those problems, and set expectations.

Successful executives are open to coaching from below—they not only welcome these inputs but actively seek them. In order to get an agenda implemented, they know project sponsorship represents an opportunity to turn a vision into reality through a set of assigned resources

The executive imperative is to support organizational learning, even at the risk of tolerating some failures. Sponsors at all levels set the tone for how failure and learning are perceived. Take the time to share thinking, standards, and expectations. Provide appropriate rewards, not only for successes but also for failures that led to heightened understanding about risks, things to avoid, and innovative approaches. The goal is to establish higher priority for continuous learning that gets recycled into new best practices.

A further executive imperative is to be conscious about the appointment of project managers. Different types of projects require different personalities for their management. The project manager that is “currently available” might not be the best choice for the project at hand—availability is not a skill set. Product centered projects, like engineering and construction projects, require managers who are sensitive to what goes on in the team and the projects, while at the same time know what to do and have the guts to do it. Product and process centered projects, like in IT and Telecom, require managers who are engaged communicators with emotional and social skills, as well as an attitude for developing others. People centered projects, such as organizational change or many business-related projects, require motivated role models who are good communicators, that is, individuals that people naturally turn to when they have questions or concerns (Müller & Turner 2010).

Vital Ingredients

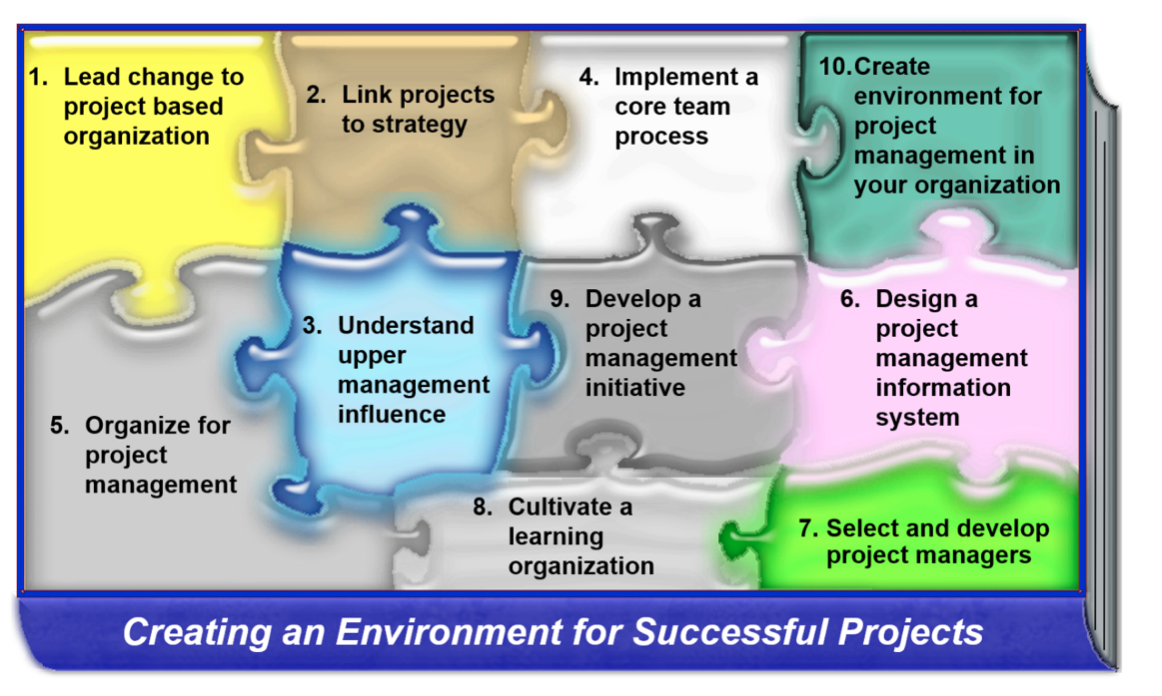

I (Englund 2019) often present ten vital ingredients or pieces of a puzzle that comprise an environment for successful projects (see figure). The pieces, however, will not stay together without glue. The glue has two vital ingredients: authenticity and integrity. Authenticity means that managers mean what they say. Integrity means that they do what they say they will do, and for the reasons they stated to begin with. It is a recurring theme in every environment where people interact that authenticity and integrity link the head and the heart, words and action; they separate belief from disbelief, and they often make the difference between success and failure.

Major upheaval requires authenticity and integrity on the part of all managers. Most change efforts do not fail from lack of concepts or from lack of a description of how to do it right. Most change programs fail when managers are hoist on their own petard of inauthenticity and lack of integrity. This failure happens because, when involved in the situations where managers violate authenticity and integrity, people sense the lack of resolve, feel the lack of leadership, and despair of the situation. When managers speak without authenticity, they stand like the naked emperor: they think they are clothed, but everyone else sees the truth. When managers lack integrity, they do not “walk the walk,” they only “talk the talk.” People sense the disconnection and become cynical.

Management cannot ask others to change without first changing themselves. Implementing a more project-friendly environment and perhaps creating a project office depend upon resolve to approach needed changes with authenticity and integrity.

The executive imperative is to avoid “integrity crimes” that cause disconnections between beliefs and actions. An integrity crime will most likely not send a person to jail but will erode all confidence that followers have in their leader.

Rethink Failure

We believe in a need to rethink views about failure. Truly, the only failure is if we fail to learn from each and every project, regardless of the outcome. An imperative is to assess how an organization views “failures.”

A more enlightened view that creates an environment for more consistent, predictable, and sustainable success is to be a learning organization that views every project as a means to improve. The focus is on overall organizational success, not just on individual project performance. People then feel like they are constantly contributing to organizational and personal knowledge. The point is to “get it right the last time”—meaning that experimentation, trial and error, bad ideas, foolishness, fun times, craziness, scrappiness, collaboration, and creativity—all have their space to operate, finally leading to successful outcomes.

Increased learning appears when people receive more feedback. The executive imperative and case for feedback hinges on establishing shared values and putting them into practice. The results will be extraordinary. Craft, with participation from all key stakeholders, a clear, concise, convincing, and compelling vision statement about portfolio success. Help all project and program stakeholders visualize how their roles contribute to that success. Early in each project, take the time to emphasize the importance of each person’s contribution. Make, and ask for, explicit commitments to be accountable for overall success and to extract the optimum contribution from each other. Demonstrate these values profusely every day, both by soliciting feedback from and providing it to others. Regularly recognize results that project and program teams contribute to organizational success. The executive imperative is to create an environment of support—a nurturing ecosystem.

Much more explicit executive support is needed in modern organizations if they truly wish not only to survive but to prosper by creating value through project-based work. It may be necessary give up a sense of control in order to get results. Control, after all, is an illusion. Nature is firmly rooted in chaos. People try to convince themselves, and their bosses, that they are in control of their projects. They may come close to this illusion, and project managers usually are far more knowledgeable about the project or program than anyone else. Try as they may, however, the fact remains that far more forces are at work in our universe than people can ever understand or control. This does not relieve executives or people in their organizations of the obligation to achieve results. What should executives do?

Take Action

Focus on results and constant course corrections to stay on track. Capture the minimal data required to keep informed. Seek information that supports action-oriented decision-making. Just because it is possible to capture and report every conceivable piece of information does not mean that should be done, nor can most organizations afford to do so. It is ill conceived luxuries that support “feeling comfortable” through excessive reports and metrics. Continuous dialogue with stakeholders and reinforcing intended results helps relieve anxieties.

Establish a portfolio management process that links execution to strategic goals, defines criteria for project selection, prioritizes projects and programs, and communicates this information to all project stakeholders. Furthermore, sponsors need to engage in negotiations about objectives and constraints for each project, clearly define problems, prioritize the importance of solutions to those problems, and set expectations.

Creating excellence in project management includes upper managers creating an environment and/or project manager taking the initiative to manage the sponsor role. Sponsor activities and behaviors vary with the organization. Many studies point to the lack of good project sponsorship as a major case of difficulties and problems on projects. Well-executed sponsorship by senior executives brings better project results. Be part of a team to make this happen through a defined sponsor selection process, a development path, on-going mentoring, constructive evaluation and feedback, and applying knowledge management.

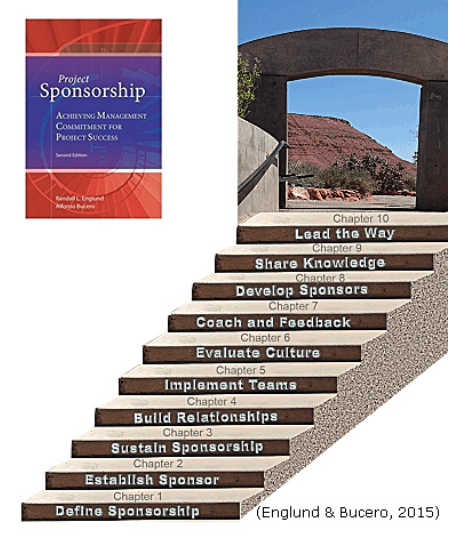

Excellence in project sponsorship may be obtained by following a set of ascending steps. These steps start with defining the sponsorship role, establishing agreed upon criteria for sponsor selection, and continuing with various ways of developing enhanced sponsor performance (see figure).

The executive imperative is to get educated on the role of project sponsorship and to set specific goals within the organization about what it means to achieve excellence in project sponsorship, such as all sponsors fully vetted through a training course, 100% of projects have sponsors assigned and active throughout the project, and sponsors present summary of benefits achieved through projects and programs at quarterly reviews.

Get Prepared

Success starts with a strong commitment to improve. Leaders become better prepared as sponsors of major projects by taking inventory of their talents, skills, and behaviors and putting appropriate action plans in place. The executive imperative is to get educated on what project sponsorship means and to set goals for effective sponsorship.

The ideal situation is proactive sponsorship—having project sponsors who are committed, accountable, and serious about the project, knowledgeable, trained, and able not only to talk the talk but also to walk the walk. Such people are trustworthy in all respects. Their values are transparent and aligned with the organization and its strategy. Such sponsors protect the team from disruptive outside influences and back the team up when times are tough.

Know that results are possible but may not follow a clearly defined path. Avoid “toxic” practices that demotivate project teams. An executive imperative is to focus on creating excellence in people, processes, and a “green” working environment. Believe that these efforts will reap the results that the organization is chartered to produce. Set a goal to create excellence in project sponsorship.

Focus

Focus on ultimately creating excellence THROUGH projects, programs, and portfolios. Creating excellence through project management means achieving greater results from project-based work…which helps an organization realize competitive advantage by executing strategy through projects in a portfolio…and significant advancements in maturity of people, processes, and the environment of a project-based organization. Consciously apply executive imperatives as necessary ingredients that make the difference for improved organizational performance. Pay attention to the vital ingredients that make the difference in creating sustainable success.

Build a Supportive Ecosystem

In this article, we use an executive management lens to shed light on building an environment for successful projects, programs and portfolios. We address the most crucial executive actions, look at the ingredients needed for success, and outline the need for actions and focus. This resembles an ecosystem—a community of interacting organisms and their physical environment. Just as in nature, trees, flowers, and animals need a suitable ecosystem in order to develop, grow and bloom. So do projects. This is not new; many well-known writers, such as Peter Senge, have used this analogy before. However, it is important that we remember it, in order to learn from it. For example, I (Englund) equate how a gardener creates the environment for plants to grow: by consciously selecting quality plants, providing suitable soil, fertilizer, light, air, and water. The roots of the plant allow nutrients to flow from the soil to the branches and leaves, where they interact with sunlight for the benefit of the plant and its environment, e.g. by turning carbon into oxygen.

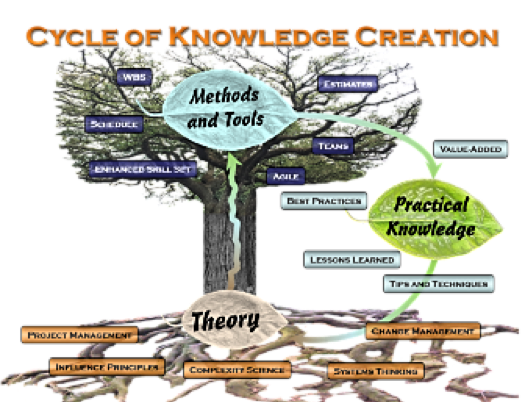

Similarly, managers participate in a cycle of knowledge creation (see figure) when they provide an ecosystem for projects, where the roots are the project management education, theory, and experience, which flow up to the branches as practices and methods, which interact as leaves with the projects and its stakeholders to create something meaningful—outputs and outcomes.

A command and control approach is still favored by many leaders. Imagine commanding a plant to “grow!” The assigned leader and objectives are clear. But what is the result? A gardener has to create an environment for the plant to flourish—he or she cannot command it to grow. Likewise, a manager in an organization has to create an environment for project success.

The natural sciences address this phenomenon through a well-known concept named genotyping and phenotyping. It says that all objects start with their particular genetic combination which allows them to grow and prosper. But it is the environment in form of light, water, air, and sustenance that hinders or supports the genetically given development. So, plants that are genetically equal when they are seeded (as genotypes) will develop differently (into phenotypes) when exposed to different environmental circumstances. Projects are not different. Joslin and Müller (2015) showed that projects can only grow and prosper when their environment allows for it. The environment should take care of the particular set of genes (such as project type, size, geography, and stakeholders) to allow them to develop into successful endeavors. It is executive management that puts this “ecosystem” in place. It is upon them to put the right soil, water and light in place in the ways described above, so that they themselves can prosper and bloom through more successful projects.

Success requires investment in an innovative infrastructure (theories, methods and tools) and the practical application of knowledge into results (fruit). The low hanging fruit is easy to harvest. Sustainable results take more effort. Reaching higher branches may involve greater risks. Of course, weeds (unplanned, unexpected, or unwanted work) occasionally creep in and need to be removed, or they may take over the environment.

The entire process begins with seeds and seed distribution. Seeds represent the potential for an organization. All growth starts small. It then builds linkages and grows organically. Additional growth comes from new branches on old trees. Success creates seeds that seek fertile ground to grow into new opportunities.

Many theories, methods and tools serve to nourish practices that lifelong students can put into action. It remains to close the loop—constantly feed the roots, refining and adding knowledge.

Be flexible and enjoy the ride!

Bio:

Randall L Englund is an author, speaker, educator, trainer, professional facilitator, and consultant for the Englund Project Management Consultancy (www.englundpmc.com). He draws upon experiences as a senior project manager with Hewlett-Packard Company (HP) for 22 years. He is co-author of seven books in the business and management field, teaches online graduate university certificate programs, and is a frequent seminar leader for the Project Management Institute (PMI). PMI awarded Randy with both the Distinguished Contributions Award and with the Eric Jenett Project Management Award of Excellence.

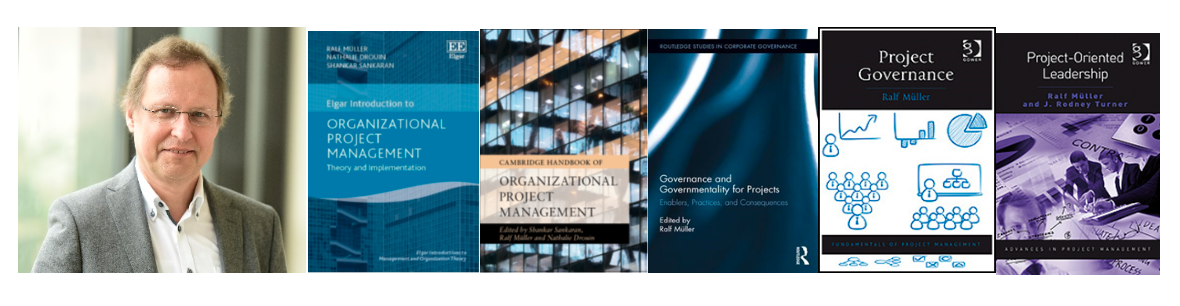

Dr. Ralf Müller is Professor of Project Management at BI Norwegian Business School and Editor-in-Chief of the Project Management Journal®. He lectures and researches worldwide in leadership, governance, and organizational project management. His research work appeared in more than 250 academic publications, including 14 books and was acknowledged with many awards, including several life-time achievement awards. Before joining academia, he spent 30 years in the industry consulting with large enterprises and governments in more than 50 different countries for better project management and governance. He also held related line management positions, such as the Worldwide Director of Project Management at NCR Corporation.

References

Englund, R. L., and Bucero, A. Project Sponsorship: Achieving Management Commitment for Project Success. (2nd ed.) Newtown Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 2015.

Englund, R. L., and Bucero, A. Patrocinio de Proyectos [Project Sponsorship—Second Edition]: Cómo alcanzar el compromiso de la Dirección para el éxito del Proyecto [Spanish edition]. Newtown Square, Pa.: Project Management Institute, 2018.

Englund, R. L., and Bucero, A. The Complete Project Manager: Integrating People, Organizational, and Technical Skills. (2nd ed.) Oakland, Calif.: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2019.

Englund, R. L., and Bucero, A. The Complete Project Manager’s Toolkit, updated. https://englundpmc.com/product/toolkit/, 2019.

Englund, R. L., and Bucero, A. The Complete Project Manager’s Toolkit. Oakland, Calif.: Berrett-Koehler, 2015.

Englund, R. L., and Graham, R. J. Creating an Environment for Successful Projects. (3rd ed) Oakland, Calif.: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2019.

Englund, R. L., and Graham, R. J. “From Experience: Linking Projects to Strategy.” Journal of Product Innovation Management, 1999, 16, 52–64.

Englund, R. L., and Graham, R. J. “Implementing a Project Office for Organizational Change.” PM Network Magazine, Feb. 2001, pp. 48–50.

Englund, R. L., Graham, R. J., and Dinsmore, P. C. Creating the Project Office: A Manager’s Guide to Leading Organizational Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

Englund, R. L., and Jain, A. “Leadership in Evolving a Project-Based Organization.” Indian Project Management Journal, Jan.–Mar. 2003, pp. 4–6.

Joslin, R., & Müller, R. “New insights into project management research: A natural sciences comparative.” Project Management Journal, 2015, 46(2), pp. 73-89.

Müller, R., & Turner, J. R. “Leadership competency profiles of successful project managers.” International Journal of Project Management, 2010, 28(5), 437–448.