Almost 50 years ago Dr. W. Edwards Deming announced that systems management was fundamental to what we can now call quality science[1], and he introduced a “system of profound knowledge[2]” as a framework for transformation of our organizational work and our entire economy[3]. He said that “An integral part of the system of profound knowledge is appreciation for a system.” But while his system of profound knowledge got a lot of attention for about 10 years, interest waned when no one could figure out how to structure or measure systems.

Almost 50 years ago Dr. W. Edwards Deming announced that systems management was fundamental to what we can now call quality science[1], and he introduced a “system of profound knowledge[2]” as a framework for transformation of our organizational work and our entire economy[3]. He said that “An integral part of the system of profound knowledge is appreciation for a system.” But while his system of profound knowledge got a lot of attention for about 10 years, interest waned when no one could figure out how to structure or measure systems.

Instead, the quality profession went only down the road of process science, inventing business process improvement, re-engineering, and now lean six sigma and its highest honor – the Black Belt. And while all these practices are valuable and laudable, they have left behind most of the promise of quality – and the greatest part of its benefit for the next century.

Despite the work of Peter Senge[4] that heralded a “system of management” that governs modern institutions,” and his observation that learning organizations must be founded on system management, no firm structure of managing systems has ever been provided – until now.

This lack of knowledge has come to an end through an emerging branch of quality science being developed by the author, and the American Society for Quality Government Division. That body of knowledge, structured system management, is the basis of a developing new standard for the Quality of Products and Services in Government, which is being developed for submission to the American National Standards Institute by the end of this year. The standard document can be downloaded at http://my.asq.org/links/1591629693.html

Current professional knowledge of systems is generally limited to the role of managers to align processes and operations, to behaviors that encourage the use of DMAIC, and to their use as control mechanisms for the comprehensive and top-down leadership frameworks of ISO and Baldrige. While any of these system management practices may rest on the use of procedures, milestones, and structure, they are not founded on standard analytic tools as are processes. And because of the failure to apply analytic tools to our key systems, we have missed the opportunity to document best-known operational practices, to standardize those practices, and to build in performance and feedback systems.

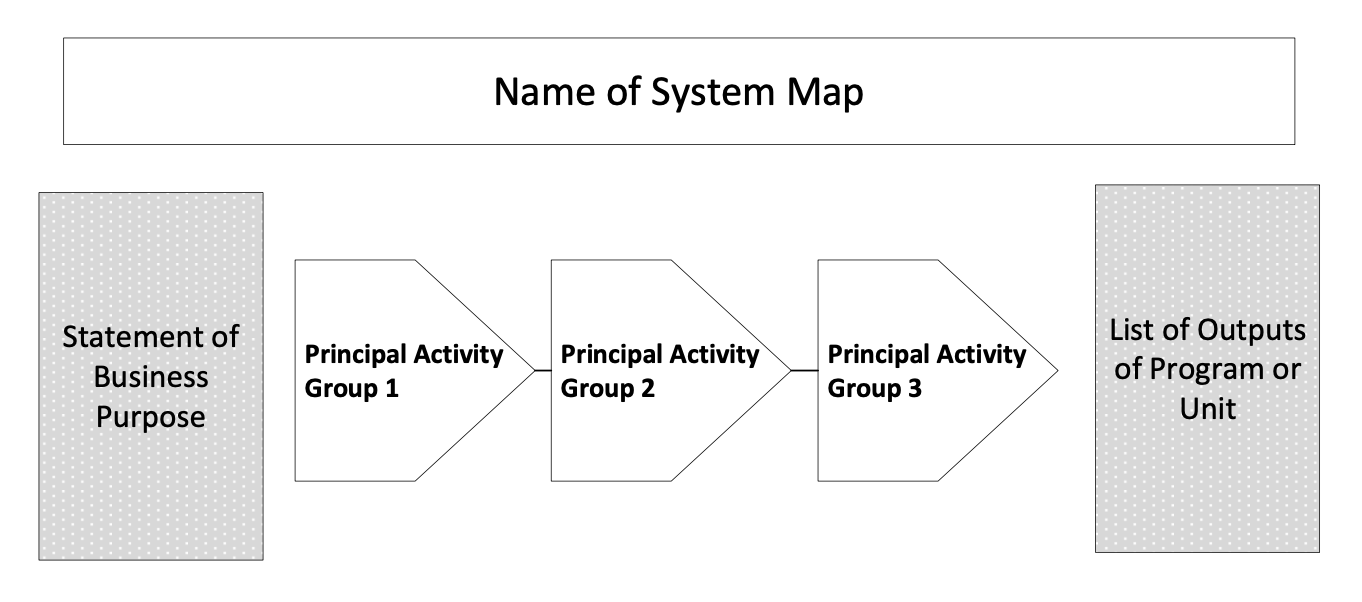

Our beginning point is the understanding that all systems are defined by an ‘aim’ or objective – what they are intended to accomplish. This is something that should be easy and natural for every executive position and program office to document. The first step is therefore one of defining its intended outputs (measurable work products) and outcomes (the impact of those products on the larger world). This becomes the first step in creation of a system map.

Beginning with the definition of purpose, we start to look for a path of how ‘we” (the system modelers) create the desired end product through intermediary value creation steps (or milestones) – which we will call principal activity groups. Specifying and documenting these principal activity groups is NOT the same as process mapping, because we recognize that systems do not always follow a singular path, and that much of its required workflow must be interpretive or dependent on intervening variables. The best interpretive model for a system map is a project plan, which has major stages of creation that are widely interpretive.

So the system map for budget management and creation may include principal activity groups of:

- Communications with production departments on needs and uses

- Management expenditures against current budget

- Projections of Future needs

- Money management and controls

- Reporting to higher authorities

Clearly these selected principal activity groups are NOT the same as process steps and are not necessarily sequential – and may or may not be done in parallel. However, the science of such a system map is reflected in the fact that each one can have clear and measurable output requirements, which is one recognized basis of quality practice. This approach is consistent with the ADLI (approach, deployment, learning, and integration/ innovation) presented in the Baldrige Excellence Framework[5], which is perhaps the best-know established model for system mapping.

The system workflow methods, in a manner similar to process mapping, is generally shown as inputs, leading to the defined principal activity groups of the office, leading to outputs, as follows:

Jumping ahead, we can see that the next steps lead to an inventory your current management efforts, and the current repetitive practices you use (standard operating practices, guidelines, procedures, and similar) to create the desired outputs and outcomes required. This is called the creation of a best known operational plan, and can be built in a consensus manner with subject matter expert input, or in a more structured method as described next.

Jumping ahead, we can see that the next steps lead to an inventory your current management efforts, and the current repetitive practices you use (standard operating practices, guidelines, procedures, and similar) to create the desired outputs and outcomes required. This is called the creation of a best known operational plan, and can be built in a consensus manner with subject matter expert input, or in a more structured method as described next.

The more granular mean of creating the best practice operational plan comes from application of basic cause and effect methods to determine the ‘causes of success’ for each principal activity group. These are referred to as “influencing factors” instead of causes.

Influencing factors should represent the planned actions that will positively influence best outputs within each principal activity group, and that are the ‘causes’ of its success. For most quality professionals this will require a bit of ‘different thinking’, because most of us have reverted to the near exclusive use of cause and effect for the determination of error causes, and in system mapping we are using cause and effect for the causes of ‘success’.

In any event, influencing factors within any system may indeed identify a key process, and that is to be expected! The importance of defining the influencing factors is that these better document the required precedents of system success (our best known operational best practice) and can also show us the leading measures (really indicators) of our future success.

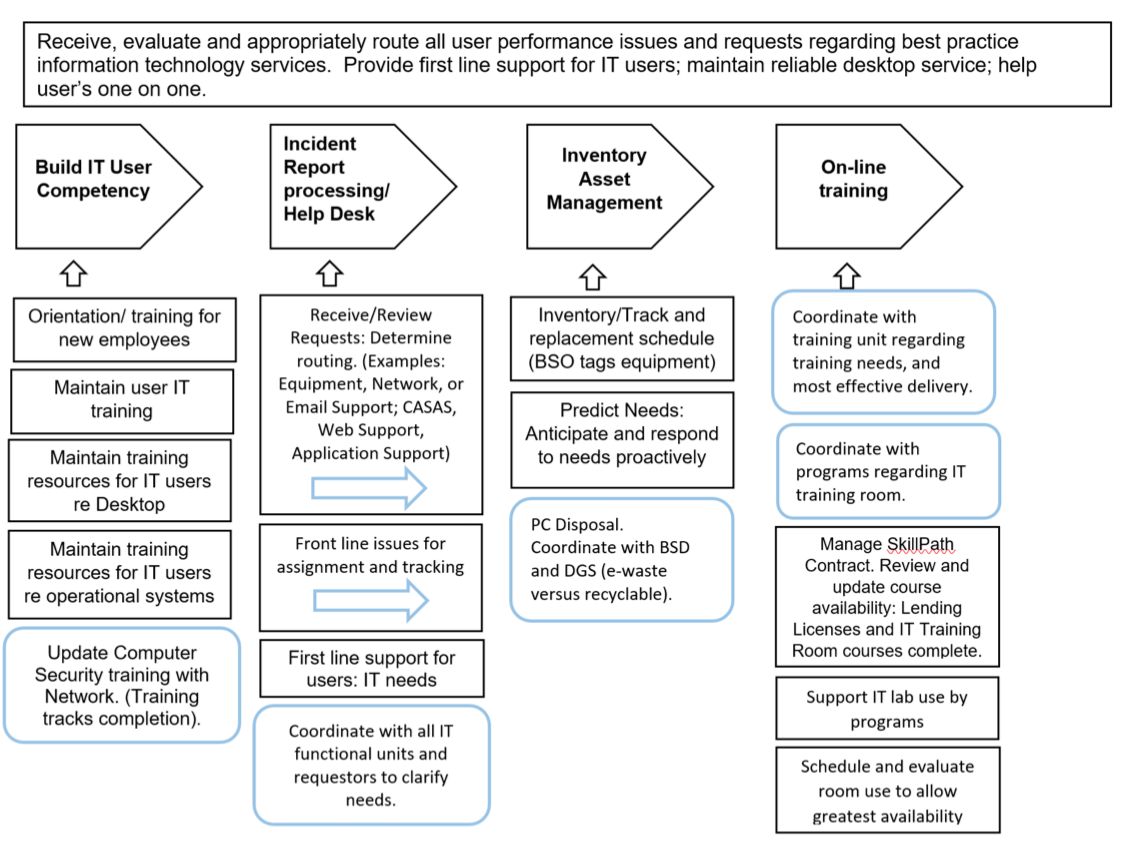

An example of a system map designed for an IT Help Desk is provided below.

Note that this map documents the system aim at the top, has established four principal activity groups, and that it has identified two key processes (with the arrow symbol) that are subordinate to the overall system management. In addition, note that the influencing factors in the boxes with rounded lines and blue shading indicate those activities that are co-dependent on other business systems.

Note that this map documents the system aim at the top, has established four principal activity groups, and that it has identified two key processes (with the arrow symbol) that are subordinate to the overall system management. In addition, note that the influencing factors in the boxes with rounded lines and blue shading indicate those activities that are co-dependent on other business systems.

In effect then, we can see a hierarchy of systems within each organization, in which each executive manager has a role to identify, standardize (to the extent possible), and improve the systems they manage and that are essential to the value creation proposition of their span of control. This can only be objectively done through a systems management framework, using documented empirical standards. Structured system mapping is the missing link for quality practice in the 21st Century, and holds the keys to broad new organizational benefits.

BIO:

Richard E. Mallory, MM, PMP, is a past Chair of the ASQ Government Division and is a Principal Consultant with Mallory Management in Sacramento, CA. He is author of three books on quality including “Quality Standards for Highly Effective Government,” Taylor and Francis Publishing, and Leadership Strategy: Creating Excellent Organizations, Trafford Publishing. He is a seven-time examiner for the US and California Baldrige Quality Awards. He can be contacted at rich_mallory@yahoo.com

Richard E. Mallory, MM, PMP, is a past Chair of the ASQ Government Division and is a Principal Consultant with Mallory Management in Sacramento, CA. He is author of three books on quality including “Quality Standards for Highly Effective Government,” Taylor and Francis Publishing, and Leadership Strategy: Creating Excellent Organizations, Trafford Publishing. He is a seven-time examiner for the US and California Baldrige Quality Awards. He can be contacted at rich_mallory@yahoo.com

[1] A term adopted by the ASQ Government Division with this definition: “The tools and knowledge associated with quality management with its origins in the Toyota Production System of the 1970’s, and embracing a broad body of professional knowledge focused on doing work right the first time. Used as the basis of the U.S. Baldrige Performance Excellence Program and the Japanese Deming Award. Embodied in the Body of Knowledge maintained by the American Society for Quality.”

[2] Deming, W.E. 1993. The New Economics. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering, pg. 94-118.

[3] Deming, W.E. 1988. Out of the Crisis.

[4] Senge, P.M. 1990. The Fifth Discipline. Doubleday. New York.

[5] Baldrige Excellence Framework, Baldrige Performance Excellence Program, National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2017-2018. Page 31.