[This is the first of a series of seven articles on the topic of risk culture and how organisations can improve their performance through uplifting their risk maturity.]

[This is the first of a series of seven articles on the topic of risk culture and how organisations can improve their performance through uplifting their risk maturity.]

Interest in risk culture has been growing since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. It is a topic that is getting more and more spotlight.

Regulatory authorities are demanding that financial institutions improve their ‘risk culture’. Workplace health and safety authorities are urging organisations to improve their ‘safety culture’. Everyone is talking about having a ‘customer experience culture’. And the list goes on.

Organisations are also recruiting for positions like “Head of Risk Culture” and “Risk Culture Manager”.

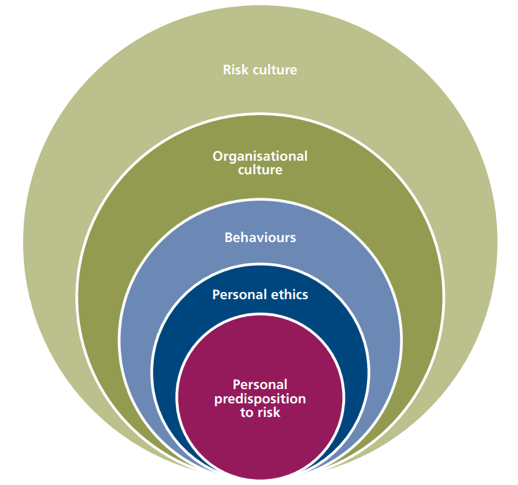

The first Google search result for the term “risk culture” comes from the Institute of Risk Management. The institute’s risk culture framework, pictured below, suggests that organisational culture is a subset of risk culture. (The Institute of Risk Management, 2012)

There is no explanation as to why and how organisational culture is a subset of risk culture, but it does not feel right.

Culture and organisational culture

Culture is the shared values, norms and expectations that govern the way organisational members approach their work and interact with each other. It helps them make decisions about how they should behave to fit in and succeed. (Human Synergistics, 2017)

Culture is about behavioural norms that are often unwritten rules about what works and doesn’t work. It relates to beliefs and assumptions about how organisational members have to behave to fit into and survive or thrive in the workplace and how they go about doing their jobs.

Organisational culture focuses more on how people believe they are expected to behave – the way that things are done in the organisation, and the unwritten rules that influence individual and group behaviour and attitudes. It is made up of organisational members’ shared values, norms, and expectations about how they should behave and interact with each other, how decisions should be made, and how work activities should be carried out.

One organisational culture, many outcomes

Many discussions and literature have centred on the need for a ‘risk culture’, a ‘customer service culture’ or even an ‘innovation culture’. This misunderstanding can lead to the thinking that there is more than one culture in an organisation.

In reality, organisations only have one culture for achieving organisational success and excellence. There will be separate outcomes generated from that single culture. One such business outcome arising from the organisational culture is ‘risk culture’.

Attempting to specifically create different organisational cultures for different business outcomes would only lead to confusion and misalignment. There will be various initiatives competing for people’s attention. This will lead to a lack of focus and alignment on the core of how to build a strong, resilient culture that will help the organisation grow and achieve all of its goals.

Focus on building only one organisational culture with many business outcomes – that includes risk, improvement, innovation, and so forth. These business outcomes will flow naturally from that one organisational culture.

Organisational culture is not a subset of ‘risk culture’. Nor ‘risk culture’ is a subset of organisational culture. Rather, ‘risk culture’ is an outcome of organisational culture.

More precisely, the organisation’s level of risk maturity is an outcome of organisational culture.

The kind of culture an organisation has will influence how they approach and practise risk management as well as how effective their risk strategies are.

Dominant culture and subcultures

A dominant culture is a set of core values shared by a majority of organisational members. When we talk about organisational culture, we generally mean the dominant culture only. This dominant culture is a macro view. It helps guide the daily behaviour of employees.

A sub-culture is a set of values shared by a small minority of organisational members. Sub-cultures arise as a result of problems or experiences that are shared by members of a department or unit of the organisation.

In the subculture, the core values of the dominant culture are retained but modified to reflect the individual unit’s distinct situation. Each subculture type aligns with the values of the organisation’s primary culture, to varying degrees.

For example, the marketing department may have its sub-culture; the purchasing department may have its sub-culture depending upon the additional values which are unique to these departments only.

Behavioural norms that influence risk management outcomes

Organisational cultures can either enable or inhibit effective risk management through either constructive or defensive behavioural norms.

When there is constructive organisational culture, people want to, rather than have to, manage risks and do good risk management. And when there is a defensive organisational culture – either aggressive or passive – organisational members avoid doing good risk management and only do risk management when they have to or are being forced, either by management or regulators, or merely as a tick-the-box compliance exercise.

There are generally three types of organisational culture – constructive, aggressive, and passive – that can influence the level of risk maturity in the organisation.

Constructive cultures encourage proactive risk management

Organisations with constructive cultures encourage organisational members to work to their full potential, resulting in high levels of motivation, satisfaction, teamwork, service quality, and sales growth. They are expected to participate without taking over and to voice unique perspectives and concerns while working toward an agreement.

Constructive cultural norms are evident in environments where quality is valued over quantity; creativity is valued over conformity; cooperation is believed to lead to better results than the competition; and effectiveness is judged at the system level rather than the component level.

These types of cultural norms are consistent with and are supportive of the objectives behind empowerment, total quality management, transformational leadership, continuous improvement, reengineering, and learning organisations. These are the potential outcomes of constructive organisational cultures.

Constructive cultures also encourage proactive management of risk. This culture propels the organisation into constructive risk-taking.

An organisational culture that enables a higher level of risk maturity builds behavioural norms and expectations of its members to behave in constructive ways, especially through informal risk management mechanisms. Informal risk management mechanisms include ‘tone from the top’ messaging; actions and role modelling by managers; and ad-hoc phone calls, face-to-face, and ‘water cooler’ conversations.

Constructive behavioural norms focus on participation, interaction, social networks, and teamwork in identifying and managing risks. Organisational members value the sharing of information and collaborating on tasks, especially risk management activities.

This collaborative approach to risk management includes:

- Setting challenging goals and developing plans to meet these goals. Striving for excellence and exploring alternatives before acting where their level of influence is specified. They have clear examples of what they should be aiming for, take on challenging tasks, and use good problem-solving skills.

- Valuing creativity and quality over quantity. Learning, growing, and taking on new and interesting tasks. Organisational members enjoy their work, doing even simple tasks well and putting their unique stamp on the job.

- Being supportive of others and encouraging others to learn and grow. Helping others think for themselves and are open to the influence of others. They resolve conflicts constructively. Planning and thinking ahead are emphasised as are exploring alternatives and options. Problem-solving involves all stakeholders whereby issues can be anticipated, and contingencies provided.

- Building strong relationships and networks. Being friendly, approachable, and open with others. Showing concern for people, cooperating with others, treating people as more important than things, and thinking about the team’s needs. Communication is comprehensive and regular.

Risks, issues and near misses are openly discussed among organisational members. Meetings about risk and performance are participative, supportive, and interactive.

Aggressive cultures encourage risk-taking

Organisations with aggressive cultures encourage organisational members to appear competent, controlled, and superior — even if they lack the necessary knowledge, skills, abilities, or experience. Those who seek assistance, admit shortcomings, or concede their position are viewed as incompetent or weak.

Aggressive cultures tend to place relatively little value on people (whether they be employees, stockholders, or customers) and operate on the philosophy that the road to success is through ‘profits over people’, finding errors, weeding out mistakes, and promoting internal competition. Being right and in control are promoted as ways of fitting in and getting ahead in the organisation.

While the decisions and strategies implemented may help them to achieve short-term gains, they typically come at the cost of longer-term success and survival.

In some ways, aggressive cultures inhibit risk maturity. This causes reactive management of risk. This culture propels the organisation into aggressive risk-taking.

The kind of behaviours that inhibit risk maturity include:

- Making snap decisions without considering alternative solutions or all the facts before thinking through.

- Being set in thinking and not open to influence.

- Gain influence by being critical and wanting to maintain superiority (point scoring) rather than dealing with it. Find fault and focus on why ideas won’t work.

- Act forceful and tough and play politics to gain influence.

- Compete rather than cooperate. Turn the job into a contest and out-perform your peers.

- Avoid all mistakes and work long hard hours to pursue narrowly defined objectives and do things perfectly. Being too perfectionistic means that deadlines can be missed.

Aggressive cultures, together with passive cultures, are controlling approaches to risk management. This approach is driven by formal risk management mechanisms. Formal risk management mechanisms include risk management policy, risk appetite statements, risk assessment templates, and risk registers.

While formal risk management mechanisms can be used to provide a visible and stable structure and defined methodologies, it is the informal risk management mechanisms that support the execution of these formal mechanisms and help to fill in any gaps. Both formal and informal risk management mechanisms are required for effective and embedded risk management.

Passive cultures encourage risk avoidance

Organisations with passive cultures encourage organisational members to lay low, blend in and conform to the status quo. Even if risks or issues are identified, people may be reluctant to raise them due to the potential negative consequences of doing so.

They are expected to do whatever it takes to please others (particularly superiors) and avoid interpersonal conflicts. Personal beliefs, ideas, and judgment take a back seat to rules, procedures, and orders—all of which are to be followed without question. It encompasses the attributes of formality, conformity, and dependability.

As a result, organisations with passive cultures experience quite a bit of unresolved conflict and turnover. Their members report relatively low levels of motivation and satisfaction. Such organisations rely on a high degree of structure, standardisation, and control to ensure reliable and consistent output. It encourages members to make decisions that support safe courses of action and information may not be shared quickly or easily.

Passive cultures can lead to inactive management of risk. This culture propels the organisation into risk avoidance.

Some of the factors that paralyse risk management effectiveness include:

- Lack of initiative and slow action on risks and issues that are identified.

- Covering up mistakes so as not to experience negative consequences through being blamed.

- Make a good impression and always follow policies and procedures even if it is no longer relevant or working.

- Reluctance to assume personal responsibility, avoid blame and shift responsibilities to others.

- Make popular rather than necessary decisions.

- Don’t want to rock the boat by taking risks or innovating.

- Avoid conflict and keep relationships superficially pleasant.

- Be liked by others and gain approval before acting.

- Clear all decisions with superiors, please those in positions of authority, and ask everyone what they think before acting.

- Push decisions upwards, take few chances and lay low when things get tough.

Organisations with passive behavioural norms can experience a situation where risk is being managed more reactively from a compliance perspective, especially through formal risk management mechanisms.

This outcome may result in organisational members behaving in ways that conform to accountability and consistency while depriving them of decision-making opportunities. They are expected to follow defined processes and rules rather than use their judgement in decision-making. This may hinder responsible risk-taking or trying innovative approaches to managing risk, resulting in risk aversion, and possibly blaming others if it does not go to plan.

Risk-taking – No risk, no gain

All businesses face risk. Organisations must take risks to survive – think Apple, Microsoft, and Google. Complacency, or risk aversion, can lead to failure – think Kodak and BlackBerry.

Leaders and organisational members need to get comfortable challenging the status quo and make it a very public statement to the effect that risk-taking is okay under the right circumstances.

Taking risks should be a strategic process, combined with creativity and teamwork, rather than just taking a blind leap. When working in a team, successful communication is extremely important. All team members should feel they are in a safe environment where they are free to be creative, share their ideas, and make mistakes. Mistakes should be accepted and learned from, rather than ostracised and deemed a failure. The learning opportunities can make risk-taking great.

A collaborative organisation that is built on constructive behavioural norms can only propel the organisation to take calculated or controlled risk-taking to increase the likelihood and extent of its success, which is the essence of what risk management is all about.

References

Human Synergistics (2017), The Role of the Board in Managing Organisational Culture.

The Institute of Risk Management (2012) ‘Risk culture: Under the Microscope Guidance for Boards’. Available at: https://www.theirm.org/what-we-say/thought-leadership/risk-culture

Professional bio

As a Chartered Accountant with over 25 years of international risk management and corporate governance experience in the private, not-for-profit, and public sectors, Patrick helps individuals and organizations make better decisions to achieve better results as a corporate and personal trainer and coach at Practicalrisktraining.com.

Given that improving risk culture and maturity has become a top of mind for many executives and risk professionals, he has conducted in-depth research into the topic and written several articles, which can be found at https://practicalrisktraining.com/risk-culture.

Patrick has authored several eBooks including Strategic Risk Management Reimagined: How to Improve Performance and Strategy Execution.