Just when we wonder what is next for the Cyber Criminals, they attack the colleges and Universities. The financial costs of school ransomware, the days lost to downtime and the number of students impacted, as these incidents snowball and become a steady source of criminal income. The history of ransomware, the most damaging ransomware attacks, and the future for this threat.

Just when we wonder what is next for the Cyber Criminals, they attack the colleges and Universities. The financial costs of school ransomware, the days lost to downtime and the number of students impacted, as these incidents snowball and become a steady source of criminal income. The history of ransomware, the most damaging ransomware attacks, and the future for this threat.

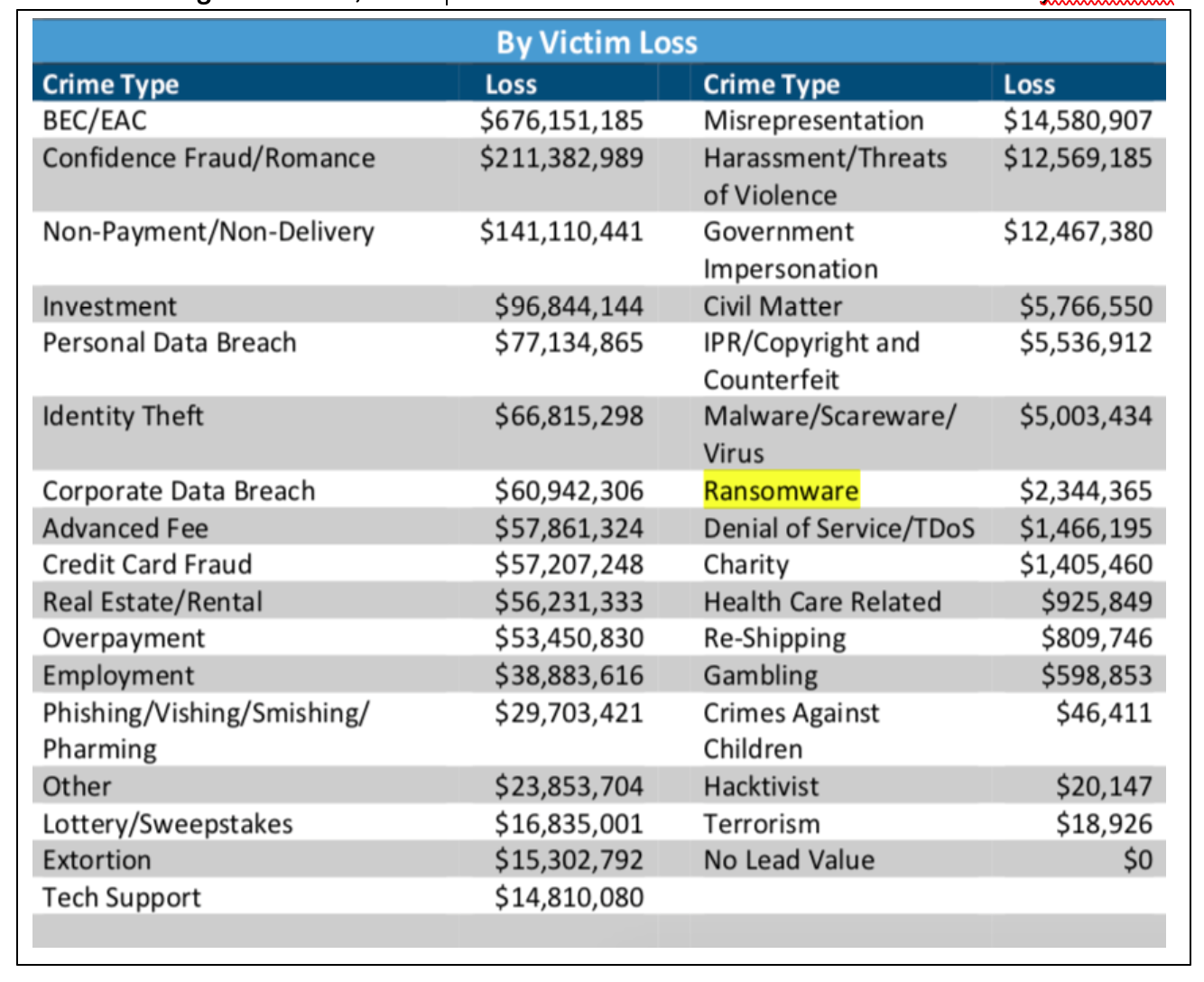

Ransomware has been a prominent threat to enterprises, SMBs, and individuals alike since the mid-2000s. In 2017, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) received 1,783 ransomware complaints that cost victims over $2.3 million. Those complaints, however, represent only the attacks reported to IC3. The actual number of ransomware attacks and costs are much higher. In fact, an estimated 184 million ransomware attacks last year alone.

In recent months, a slew of cyberattacks hamstrung domestic meat and petroleum production and set off a few alarms at a Florida water treatment facility. With companies willing to shell out big bucks to bring their companies back online and risk further fallout, it’s becoming increasingly clear that no sector is off-limits, this includes education as students return to the classroom. Comparitech released new research highlighting the financial costs of school ransomware, days lost to downtime and more as cybercriminals set their sights on education organizations.

“Many schools cannot operate without their computer systems, and some schools have had to cancel classes due to ransomware attacks,” “Resolving a ransomware attack without paying the ransom takes about two weeks on average, which is far too long for kids to be out of school. So, ransomware creates urgency that makes schools more likely to pay up.”

Overall, the findings detail shifting cybersecurity trends across the education landscape. While total attacks on education centers appear to be on the decline, at the same time, these attacks are impacting a greater number of students with many more schools potentially impacted.

According to the findings, there were 77 ransomware attacks involving schools and colleges in 2020, representing a 20% decrease compared to 2019, yet, more than 1,740 of these institutions were “potentially affected;” a 39% increase from the year prior. More than 1.3 million students “could have been impacted” by these attacks in 2020, representing a 67% increase compared to 2019.

These cyberattack patterns have shifted markedly in the last few years. For example, there were 10 reported ransomware attacks in 2018, compared to 96 in 2019 and 77 in 2020, according to the report. However, as Pomfret points out, this year-over-year drop-off “appears to have been in favor of larger, more targeted attacks on bigger school districts with higher budgets and larger numbers of students.” So, why are cybercriminals choosing to focus on schools and where are these systems particularly vulnerable?

“Schools are often strapped for cash and therefore can’t afford to invest a lot of resources into hiring qualified IT staff, keeping those staff trained, paying for audits or penetration tests, and buying up-to-date hardware and software,” Pomfret said. Additionally, he explained that schools often have online portals for student access and these platforms “serve as public-facing attack vectors and can, in turn, be targeted by remote hackers.”

“A lot of staff at schools work on computers regularly but aren’t IT experts, which creates more opportunities for hackers due to operational security missteps,” Pomfret continued.

How to secure your email via encryption, password management and more (TechRepublic Premium)

In 2020, Texas topped the list, as the Lone Star State accounted for 13% of all U.S. ransomware attacks followed by No. 2 California (9%), according to the report; in terms of students affected, Nevada ranked No. 1 with 328,991 students impacted in 2020. As Pomfret explains, Nevada is home to the Clark County School District, one of the largest school districts in the U.S.

“As the county didn’t pay the requested ransom, the hackers (Maze) dumped student records. The data breach report filed says 44,139 students were thought to have been affected by this aspect of the attack. The county and its staff and students also faced ongoing system disruptions in the month that followed,” In order, Maryland and Virginia ranked second and third with 10.5% and 8.8% of their students impacted, respectively.

So, how much are these attacks costing school systems? The short answer: The picture isn’t fully clear. As “only a handful of providers publicly release” these data as these organizations “understandably” do not want to “discuss ransom amounts or whether they have paid these as it may incentivize further attacks.” That said, the report said the estimated cost of these education sector ransomware attacks is valued at $6.62 billion in 2020 with hackers receiving “at least” $1.9 million in payouts.

Following an attack, schools spend an average of 55.4 days recovering and lose almost a full week (nearly 7 days) to “downtime,” according to the report. Based on available data, Biscoff postulates that ransomware attacks could have resulted in “201 days of downtime and 1,108 days of recovery time in 2020.”

From January 2018 through June 2021, schools and universities suffered 222 attacks, resulting in 1,387 days of estimated downtime with a cost of more than $17.3 billion, according to the report, although this sum does not include the 9,525 days spent recovering and these “potential recovery” costs.

“Despite the rise of ransomware’s prominence in the news, the number of ransomware attacks against schools actually decreased from 2019 to 2020,” Biscoff said. “However, ransom demands, and the number of students impacted by ransomware attacks have continued to grow. I’ll be interested to see how these trends play out post-pandemic, as lockdowns and the shift toward remote learning certainly had a role to play.”

Strengthen your organization’s IT security defenses by keeping abreast of the latest cybersecurity news, solutions, and best practices.

Schools could be ripe for cyberattacks amid ransomware open season (TechRepublic) Security threats on the horizon: What IT pro’s need to know (free PDF) (TechRepublic) Checklist: Securing digital information (TechRepublic Premium) Cybersecurity and cyberwar: More must-read coverage (TechRepublic on Flipboard)

Ransomware and other cyberattacks on K-12 schools have increased, especially as districts lean further into technology use for teaching and learning, and as cybercriminals get more sophisticated.

Since the 2022-23 school year began, a handful of school districts have been hit with cyberattacks. Most recently, the nation’s second-largest school district, Los Angeles Unified, was targeted by a ransomware attack over the Labor Day weekend. In a ransomware attack, cybercriminals break into a district or school’s network and take data and encrypt it, preventing the district from accessing the data.

Attackers will decrypt and return the data if the district or its insurance company pays a ransom. Attackers typically threaten to release student and employee data to the public if they aren’t paid.

Attackers will decrypt and return the data if the district or its insurance company pays a ransom. Attackers typically threaten to release student and employee data to the public if they aren’t paid.

Guidance from the FBI and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency discourages paying the ransom because it doesn’t guarantee that the data will be decrypted or that the systems will no longer be compromised. Paying the cyber criminals also encourages hackers to target more victims.

[If a lot of sensitive information has been stolen,] it becomes a much different risk calculation for superintendents and for school boards.

Doug Levin, national director of K12 Security Information Exchange Every district has its own unique risk calculations.

Despite the guidance from the two federal agencies, the question of whether to pay ransom does not always have a simple answer.

“I would be hesitant to judge any school district harshly for whatever decisions they make—whether to pay or not to pay—after they’ve become a victim,” particularly in cases where districts have been locked out of all their systems and large amounts of data have been stolen, said Doug Levin, the national director of the K12 Security Information Exchange, a non-profits focused on helping K-12 schools prevent cyberattacks.

If a lot of sensitive information has been stolen, “it becomes a much different risk calculation for superintendents and for school boards,” Levin said.

District officials have to weigh the risks of paying an extortion demand against the potential to restore operations and keep sensitive information from being publicly disclosed,

Don Ringelestein, the chief technology officer for Maine Township High School District 207 in Illinois and a board member for the Consortium for School Networking, agreed that the decision to pay or not to pay a ransom “depends on each district’s situation.” Ringelestein said his district, so far, has not been the victim of a successful ransomware attack.

The first thing district leaders should find out is what data the hackers are holding for ransom, said Ringelestein. If it’s something that isn’t sensitive or critical, it’s most likely not worth paying the ransom.

If the hackers have infiltrated the student information system, the finance system, or other critical systems, then the next thing district leaders need to figure out is whether they have “immutable backups,” Ringelestein said. An immutable backup means the stored data is fixed, unchangeable, and can’t be deleted. If there are immutable backups, then the district would just need to restore the data and “keep a very close eye” on the system to ensure the hackers aren’t still in the systems.

If the district doesn’t have those backups, then district officials, along with their cybersecurity insurance company and/or law enforcement, might need to negotiate to get the data and the affected systems restored.

“In some cases, you might have to [pay the ransom], but then you better make sure you put controls in place [so] that the same actor doesn’t come back and do it again,”

In the Los Angeles schools case, the hackers leaked the data they had on Oct. 1 after Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said he wouldn’t negotiate with or pay ransom to the cybercriminals. After analyzing the leaked data, the district found there was “no evidence of widespread impact as far as truly sensitive, confidential information,” Carvalho said in an Oct. 3 press briefing.

The school district’s technicians were able to stop the attack while it was in progress, which limited the damage to the district’s systems and data, Carvalho said.

Most districts have insufficient cybersecurity resources.

Not all school districts have the cybersecurity resources that Los Angeles Unified does, though.

In recent years, a few districts, such as Cedar Rapids Community School District in Iowa and Judson Independent School District in Texas, have had to pay ransom fees to get their data and systems back because they didn’t stop the attack in time or because rebuilding their systems would be more expensive.

There isn’t any concrete data on how many districts have paid ransom because they usually don’t disclose that information, according to Levin.

“Most districts don’t have somebody who’s in charge of cybersecurity, or they do but it’s another duty as assigned,” Ringelestein said.

“The job market works against us in education. It’s hard for us to get that kind of talent,” he added. “If a chief information security officer can make $250,000 in the private sector, nobody in education is going to pay that.”

Cyber Hackers Attack Schools More Often Than You Think, But there are Ways to Stop Them, Including

- One solution for the staffing issue could be neighboring districts sharing a chief information security officer or hiring a managed service provider to oversee a security operations center, Pomfret said.

- “Given the school funding situation and given our ability to hire and our staffing situation, I think that’s the way to go,” he said.

- Even though cybersecurity is a top priority for state ed-tech leaders, it is one of the top three unmet technology needs, according to a State Educational Technology Directors Association report. Only 8 percent of respondents to a survey said their state provides “ample” funding for cybersecurity risk mitigation efforts; 40 percent said their state allocates “very little” funding.

- “The best advice for school districts is to avoid being a victim of ransomware in the first place,”

Some other ways to stop cyberattacks include:

- Doing a risk assessment to figure out where your vulnerabilities are;

- Having a cybersecurity plan that the district practices regularly.

- Training employees and students on common tactics hackers use.

- Backing up data regularly and making sure it’s separate from the main network; and putting in place multifactor authentication systems.

Bio:

Dr. Bill Pomfret of Safety Projects International Inc who has a training platform, said, “It’s important to clarify that deskless workers aren’t after any old training. Summoning teams to a white-walled room to digest endless slides no longer cuts it. Mobile learning is quickly becoming the most accessible way to get training out to those in the field or working remotely. For training to be a successful retention and recruitment tool, it needs to be an experience learner will enjoy and be in sync with today’s digital habits.”

Every relationship is a social contract between one or more people. Each person is responsible for the functioning of the team. In our society, the onus is on the leader. It is time that employees learnt to be responsible for their actions or inaction, as well. And this takes a leader to encourage them to work and behave at a higher level. Helping employees understand that they also need to be accountable, visible and communicate what’s going on