In recognition of May as Mental Health Awareness Month, I cannot help but put gun violence at the center of my paper to encouraged employers to create supportive workplaces that destigmatize mental health struggles and to provide access to counseling and other vital resources.

In recognition of May as Mental Health Awareness Month, I cannot help but put gun violence at the center of my paper to encouraged employers to create supportive workplaces that destigmatize mental health struggles and to provide access to counseling and other vital resources.

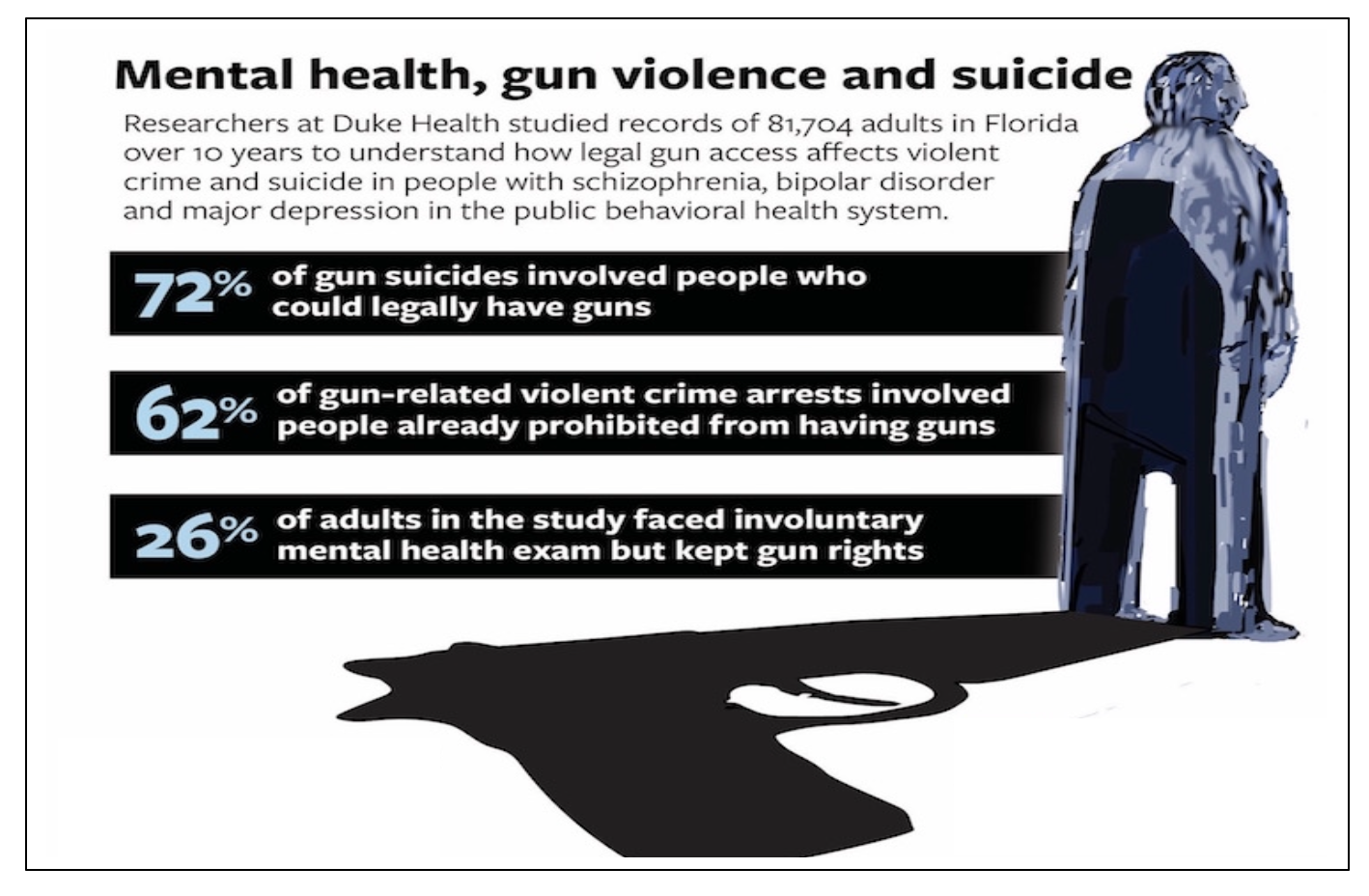

Shedding Light on Personal Struggles is the real story — and the real need — regarding mental illness and violence is suicide. Not only are most firearm deaths suicides, but most suicides are causally linked to mental illness.

Given these realities, erroneously placing mental illness at the center of the American gun violence narrative stymies solutions to both these public health problems, which come together only on their edges.

Associating mental illness with violence reinforces stigma and unwarranted fear of people with mental illnesses — people who need support to recover from serious brain-based conditions.

In addition, some mental health advocates may understandably be tempted to focus on violence in the quest for crucial funding of services but making such a case can led to misaligned priorities, misdirected resources, and misapplied coercive interventions against people with mental illnesses.

The real story — and the real need — regarding mental illness and violence is suicide. Not only are most firearm deaths suicides, but most suicides are causally linked to mental illness.

Even when we look at suicide, though, the relationship between mental illness and risk is complex and nuanced. For example, there are important gender differences in the role of both mental illness and firearms in suicide. Extensive research on suicide risk factors suggests that mental illness is implicated in about 7 out of 10 suicides among women, but only about half of men who die by suicide. Social and economic stressors are stronger determinants of suicidality among men, who are also significantly more likely than women to use a firearm in a suicide.

Despite such complexities, what is clear is that people who may be suicidal should not have access to firearms when they are most at risk. Suicidality is often a passing urge — many people who consumed large amounts of pills and survived later say they regret their suicidal action — and firearms offer little chance of survival.

What can we do?

To help address the risk of gun-related suicides, providers need the training, skills, and resources to systematically screen patients for depression and discuss firearm safety when clinically indicated. At the institutional level, hospitals and health care systems also should incorporate policies and guidelines to facilitate comprehensive screening for depression and educate patients about firearm safety. For example, electronic health records could prompt clinicians to screen patients and conduct firearm conversations.

Medical schools should universally teach future clinicians the skills necessary for discussing firearm safety. Indeed, subject matter experts have developed consensus guidelines for educating all medical professionals about firearm injury and prevention, and several institutions have robust firearm-related efforts. Part of such education must involve discussing firearms with patients in ways that are respectful of their values and sensitive to their cultural experiences. Ample guidance in this area is available, such as the use of terminology that is most likely to resonate with different types of patients.

Clinicians should also learn about ways to temporarily limit access to firearms when patients present a risk of harm to themselves or others. Depending on the state, or Province, options for limiting access include Extreme Risk Protection Orders (ERPOs) — also known as red flag laws — in which family members and law enforcement personnel may request that a judge require a person to temporarily relinquish their firearms. In addition, several states allow individuals who are concerned that they may harm themselves in the future to enroll voluntarily in a background check database that would prevent them from purchasing a firearm without a waiting period.

In 19 states and the District of Columbia, clinicians can also contact law enforcement to request that a judge issue a restraining order to separate firearms temporarily from people at high risk of harming themselves or others. In four states, clinicians are authorized to petition a court directly for an ERPO consistent with HIPAA privacy rules and with some legal immunity.

These orders are time-limited, carry no criminal penalties, and do not create a criminal record. They also offer due process protections, respect the Second Amendment, and are supported by most Americans, including a majority of gun owners.

We will never solve the problem of gun violence in America by “fixing mental health.” That is a simplistic notion, one that focuses on a serious but different public health problem.

The causes of gun violence in the United States are numerous and complex — and so are the solutions. But if we pursue proven measures designed to prevent access to firearms among people most at risk for perpetrating violence at their riskiest times, we will be moving significantly in the right direction. If health care providers use their influence to advocate for evidence-based gun safety policies and practices; if we implement firearm safety conversations systematically in clinical care; and if we teach these skills to future providers, we will save many more lives than if we only work to heroically treat yet another catastrophic shooting victim.

“While mental health conversations were on the rise prior to 2020, enduring months of lockdowns [during the COVID-19 pandemic] put us all on notice,” Dr. Pomfret said. “The pandemic exposed how much we have neglected our collective mental well-being. “Gun violence can help us reduce suicide deaths.

Along with COVID-19, labor strife, financial struggles and social unrest led to “a wave of emotional distress,” Pomfret noted. Now, “the word is out, but awareness alone is not a solution,” he said. Employers need to “take action to advance mental health for all.”

Phelps, who won 23 gold medals in five Olympic Games, has been forthright about his mental health struggles, which have included bouts of depression, anxiety, and thoughts of suicide. “Mental health advocacy is something I live every day,” he said. “There are positive days and days I struggle, days that are dark. … I’ve learned that I’m not the only human being that’s going through this. We need to normalize these discussions and share that it’s OK not to be OK and that there is support available.”

Pomfret emphasized the need to focus on physical health and mental health together, because “our heads and our hearts are connected.

Pomfret emphasized the need to focus on physical health and mental health together, because “our heads and our hearts are connected.

We get our teeth cleaned, we get flu shots and wellness checks, but we don’t talk about our mental health.” Worse, people are often judgmental toward those who are experiencing mental health issues, viewing them as “weak.”

If someone is diagnosed with cancer or is a diabetic, “we have support groups, walks and fundraisers,” he said. “But if someone says, ‘I have anxiety, I have depression, thoughts of suicide, and I’m really struggling,’ it’s almost seen as a defect.”

Pomfret shared that after his second daughter was born, “his wife had postpartum anxiety and no idea what I was experiencing. We have to remove barriers to people getting care that helps them to figure out what’s going on.”

He added, “the more we push down and stifle struggles with mental health, the harder it comes back. The more we normalize these conversations, the more the ripples go out. We have gone far too long making people feel ‘less than’ because they have mental health struggles. We need to have these conversations, so people feel it’s OK to show up at their best or at their worst and not feel they must hide, Gun violence is one more aspect.

What Employers Can Do

Employers can set up cultures that are inclusive and that encourage leaders and colleagues to share their struggles, Pomfret said. “Those are powerful stories.”

Employers can also refine their mental health benefits to be more effective, such as by offering access to virtual therapy services.

“Remember that when people are down and not feeling their best, the last thing they need is something hard to navigate. Benefits and health leaders must work hard to make this easy,” he said. “Make sure that people have access to quality care and can measure their improvements. Talk about mental well-being as part of the job. Create colleague resource groups mental well-being resource group has more than 1,500 employees. Work with community organizations.”

Phelps, an ambassador for Talk space, a virtual care provider, said that for 60 percent of the service’s users, this is their first-time seeking help from a therapist. Virtual counseling via a phone app or computer can be less intimidating and more timely and readily available compared to visiting a therapist’s office.

Phelps also recommended that workplaces provide “quiet spots where people experiencing stress or anxiety can go to decompress.”

Significantly, he said, “we can do more to overcome the stigma, to make it OK to share that ‘I have depression. I have anxiety.’ ”

For those dealing with mental health issues, he added, “not every day is going to be perfect, but as long as we can take baby steps forward, then we’re winning.”

Bio:

Dr. Bill Pomfret of Safety Projects International Inc who has a training platform, said, “It’s important to clarify that deskless workers aren’t after any old training. Summoning teams to a white-walled room to digest endless slides no longer cuts it. Mobile learning is quickly becoming the most accessible way to get training out to those in the field or working remotely. For training to be a successful retention and recruitment tool, it needs to be an experience learner will enjoy and be in sync with today’s digital habits.”

Every relationship is a social contract between one or more people. Each person is responsible for the functioning of the team. In our society, the onus is on the leader. It is time that employees learnt to be responsible for their actions or inaction, as well. And this takes a leader to encourage them to work and behave at a higher level.