Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of his employer, GxP Lifeline, its editor or MasterControl Inc.

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of his employer, GxP Lifeline, its editor or MasterControl Inc.

The long history of Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) requirements within the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Quality System Regulations—and specifically 21 CRF 820.100 and ICH Q10—implies that most biomedical companies have evolved a certain level of mature thinking and a good understanding of the fundamental requirements for CAPA systems. This, unfortunately, is not always the case. I am currently spending a lot of time working with client companies in remediation mode; that is, after FDA has found enough flaws to issue a 483 or warning letter. I would like to point out some common CAPA problems that can be proactively rectified to avoid citations in the first place.

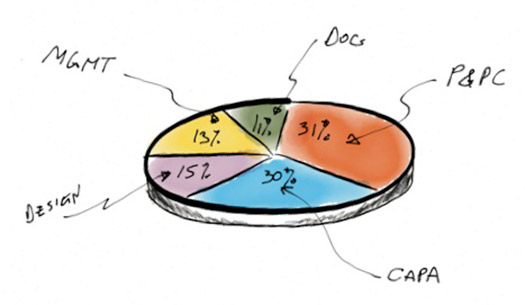

First, some data. FDA’s 2010 data on warning letters by QMS subsystem shows nearly a third (30%) are still being issued for CAPA problems. Data on 483s shows a similar breakdown (32%).

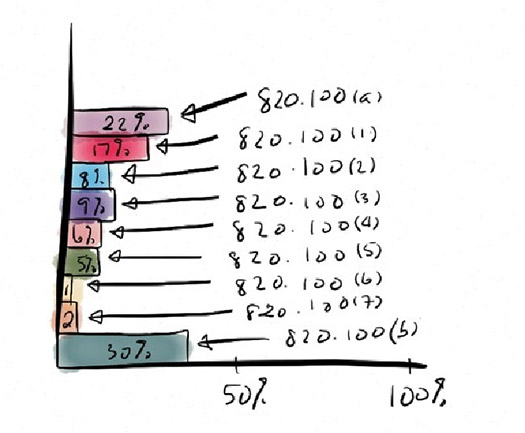

Within the CAPA subsystem, the citation breakdown shows that a full 22% do not even have a CAPA system and 30% that do not properly document the process. The rest of the citations are all are related to the basics of the process, as outlined in 820.100. A well-implemented CAPA process will generally avoid any of the items cited in the chart shown below. Of particular note: 820.100 (a) “establish and maintain procedures,” 820.100 (1) “analyzing processes” and 820.100 (b) “documentation” figure prominently. Items 820.100 (1) through (7), the basic CAPA process, are also frequently cited.

The lack of implementation of the basic CAPA process is startling. For illustrative purposes, I have highlighted below a schematic of how ISO 13485 and 820.100 describe the CAPA process. Omitting, de-emphasizing or underperforming any of these steps will put your organization on FDA’s watch list. It is not a matter of “if” you will land there—it is a matter of “when.”

Let’s go through each one in a bit more detail so it becomes clear how to avoid FDA concerns.

QUALITY EVENTS

Although not specifically stated in 820.100, an effective CAPA system must have a method to handle and channel incoming quality events. Whether they are non-conformances, MDRs, complaints, production incidents, etc., the system needs to be flexible enough to handle and capture the multiple sources. The system should then be able to channel it into the proper category and allow capture of the unvarnished information.

I often see a disconnect where companies do not handle their various quality issues the same way. MDR’s are handled differently from non-conformances, and so on. These disparate methods often are not passed on to a CAPA system the same way or even to the same CAPA system.

Hint: FDA does not like to see multiple policies/procedures for multiple non-conforming systems. It makes sorting thought all the quality events/systems cumbersome, which in turn makes FDA grumpy.

ISSUE REVIEW

A risk-based initial understanding and disposition of the event is then performed. Based on pre-set acceptance criteria (risk matrix), the system should provide a risk-based decision on whether to escalate into a CAPA, or to justifiably closeout and document.

Not implementing a risk-based gateway approach to sort CAPAs is cause for concern with FDA. Too many events will end up in CAPA, choking the system (“death by CAPA”). Hint: use a gateway with a risk-based system to identify the events that truly need to go through a CAPA investigation. The majority of events should not go to CAPA.

INVESTIGATE

At this step, the issue is now a CAPA and a formal investigation needs to be performed. This is where the initial information from issue review can be formalized and facts gathered into an investigation. This step is typically not performed in an office but out on the line/site, asking questions and receiving data from the field.

I often see teams jump to implementing a solution before they have performed an investigation (“jumping to solutions”). How can a root cause be properly identified without first gathering all the data and performing an investigation? Hint: the root cause is not always a ‘smoking gun’ and likely cause can change from pre-conceived notions after an investigation is performed.

ROOT CAUSE

Once the data has been analyzed, a root cause can be assigned. This is not always easy to find. Tools such as comparative analysis may be needed. At least two possible root causes should be tested and evaluated with documented evidence of final likely root cause assigned to the investigation.

Failure to completely examine all likely causes by testing against the facts can often lead to an incorrect likely cause. Hint: use comparative analysis (what is happening versus what is not happening) to eliminate unlikely causes.

VERIFY/VALIDATE

FDA does not accept that finding a solution to the root cause is alone sufficient to correct or prevent the problem. The proposed solution must be tested (verified and validated) to ensure 1) the solution worked, and 2) there were no unintended consequences of implementing the proposed solution.

Perhaps the most consequential problem I see with CAPA investigations is not verifying and validating the proposed solution. The risk of unintended consequences is significant, even for what may seem like a routine solution. Hint: FDA cites a lack of verification and validation often as one of the major causes of a product recall.

IMPLEMENTATION

Once a solution has been verified and validated, the solution can be implemented. A trending and tracking system should be utilized to ensure the solution continues to fix the problem post-implementation.

I often see companies implement Band-Aids or half-baked solutions that merely mask the symptoms and do not address the underlying condition. Why go through all the trouble of a formal CAPA investigation, only to arrive at a solution that does not really fix the problem? Hint: make sure the solution is SMART: Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, Time-bound.

DISSEMINATE

The implemented solution must be properly proceduralized and trained to insure repeatability and adherence to procedures. Documented evidence of training must be shown.

Lack of documented implementation is often cited in warning letters and 483s. CAPAs are not immune to this issue. What is the point of implementing a solution if it is not documented? What are the chances of a new procedure reverting to the previous procedure without proper training and retainment?

Hint: FDA considers anything “to not have happened if it is not documented.”

MANAGEMENT REVIEW

Any CAPA that was associated with high risk (most CAPAs by definition) should be sent to principal quality staff for review. Closeout should be documented and signed by ranking quality officers.

I think that a CAPA assigned a high enough risk should be brought to the attention of senior management. Almost every FDA inspection I have witnessed includes considerable time reviewing CAPAs. Uninformed senior management tends to be displeased when FDA discusses CAPAs of which they are unaware. Hint: inform senior management of all CAPAs with high risk ratings by using your issue review gateway system.

In conclusion, you can practice warning letter and 483 avoidance by adhering to some of the most basic steps outlined above. You can be proactive now, or you can see the likes of us compliance/remediation experts later, when you are required to issue a response and action plan to fix these problems.

Note: This article is used with permission from GxP Lifeline and has been previously published at www.mastercontrol.com.”

Bio:

Peter Knauer is a partner consultant with MasterControl’s Quality and Compliance Advisory Services. He has more than 20 years of international experience in the biomedical industry, primarily focusing on supply chain management, risk management, CAPA, audits and compliance issues related to biopharmaceutical and medical device chemistry, manufacturing and controls (CMC) operations. He was most recently head of CMC operations for British Technology Group in the United Kingdom and he has held leadership positions for Protherics UK Limited and MacroMed. Peter started his career at Genentech, where he held numerous positions in engineering and manufacturing management. Peter is currently chairman of the board for Intermountain Biomedical Association (IBA) and a member of the Parenteral Drug Association (PDA). Peter holds a master’s degree in biomechanics engineering from San Francisco State University and a bachelor’s degree in materials science engineering from the University of Utah. Contact him at

pknauer@mastercontrol.com.